This article is part of the series Legalizing Inexpensive Housing

After a seven-year campaign, Portland on Sunday formally lifted a series of 97-year-old bans on seven different types of homes.

Becoming legal today on the vast majority of residential lots in Portland: a duplex, a triplex, a fourplex, a mixed-income or below-market sixplex, a large group co-living home, a double ADU, and a tiny backyard home on wheels.

Sunday, August 1, is the effective date for a series of reforms passed by Portland City Council over the last 12 months, including most provisions of the city’s “Residential Infill Project” and “Shelter to Housing Continuum Project.” They add up to a dramatic overhaul of the low-density zoning that Portland, like many other North American cities, created in the 1920s.

But today’s milestone comes with an implicit question. All these options may now be legal on paper. But will any of them actually be built?

It’s a question that matters not just in Portland but across the continent, as cities like Charlotte and Sacramento and larger jurisdictions like British Columbia and Vermont consider similar reforms. In the US Congress, incentives for reforms like these might make their way into Democrats’ next reconciliation bill.

So Sightline decided to do the math.

Here’s how we estimated which homes will get to exist

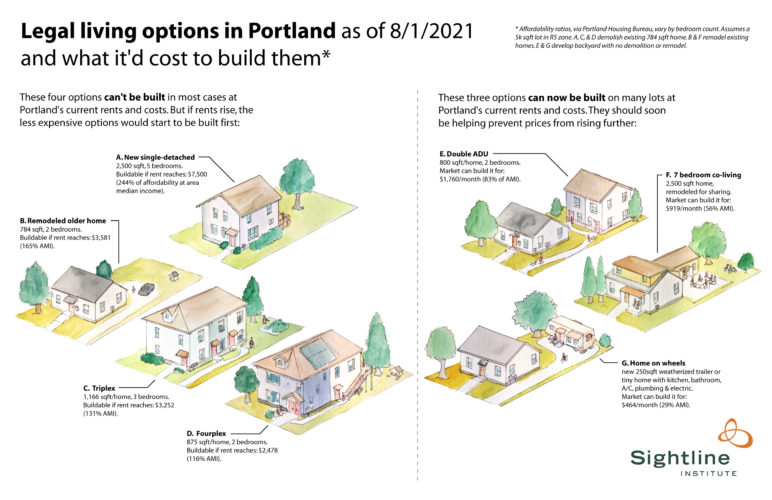

Working with Portland-based consultant Neil Heller, a faculty member at the Incremental Development Alliance, I chose a hypothetical $320,000 lot in Portland’s Montavilla neighborhood with an existing 784-square-foot house. Then we estimated what it’d cost to create each of the potential newly legal options.

We added a construction cost of $200 per newly built square foot (a bit lower for the largest home) to figures for demolition, site preparation, local development fees, rental operating costs, property taxes, loan costs, an average five percent vacancy rate, and a competitive return on investment (10 percent cash-on-cash returns in year three, a figure that covers mortgage payments and return on cost). That gave us the minimum rent that’d be required to create each of the newly legal homes.

For projects where the minimum rent required came in above Portland’s current market rate, then the project wouldn’t get built right now—the property owner would presumably do the same math and realize they’d fail to get the rent they’d need to make money on the deal.

But for projects where the necessary rent came in at or below Portland’s current market rate, homes can immediately be built.

Five Big Takeaways

1) On most urban lots, legalizing smallplexes would mean nothing at all for many years.

Whenever a city discusses this sort of proposal, many people leap to the conclusion that because four is more than one, legalizing fourplexes on any lot will mean that every lot will become a fourplex.

I sympathize. It’s exactly how I used to think this stuff worked myself.

These figures show why it doesn’t. To cover the cost of buying and demolishing a habitable structure in Montavilla, a fourplex builder would need to charge $2,478 a month (or, if it’s a condo or townhouse project, a similarly high sale price) for each of four two-bedroom homes. In Portland, that would no longer be wildly out of market at 22nd and Hawthorne, but at 92nd and Davis it’s not happening, at least not yet—and the fourplex isn’t going in at 22nd and Hawthorne, either, because the initial purchase price there would be much higher than $320,000, forcing the necessary rent higher still.

For new triplexes, duplexes, or a new replacement oneplex, the post-demolition price would have to be even further out of whack—monthly rent of $3,252, $4,543, or (woah) $7,500 for the oneplex. (Oneplexes are expensive!) Again, none of that is happening in Montavilla.

Along the California coast, or on Long Island, or in north Seattle, some of those prices might work—which is a reflection of the fact that some cities are more desperate for housing than Portland is and would have more to gain from legalizing smallplexes. But even there, any transformation would be slow.

This is the economic explanation for why a neighborhood that has legalized fourplexes looks almost the same 40 years later. It’s also why the older neighborhoods in North American cities, built before zoning arrived in the 1920s, often have a mix of apartments, plexes, and detached homes.

Left to its own devices, a city is like a forest. Lots of new things are growing; lots of old things are living their lives.

2) The best way to make an infill project work is to avoid demolition.

They call this sort of housing “infill” for a reason. As these figures show, it’s at its best when it nestles into the spaces between homes.

Environmentalists have long talked about how cities can “grow out” or “grow up.” Re-legalizing “missing middle” housing is more about growing in—converting yards and driveways into living spaces.

These figures suggest that’ll happen quite a lot. A project that creates two 800-square-foot accessory dwellings—essentially a backyard duplex, capped at 20 feet tall—starts to make economic sense if each newly built two-bedroom could rent for at least $1,760 per month. And because it doesn’t require demolition, that break-even value applies not just to Montavilla but anywhere in Portland.

(Building a double ADU of this size does require enough space in the backyard and a primary home of 1,100 square feet or so, depending on the details.)

Maybe the most eye-catching thing we found, though, is the cost of installing a semi-permanent home on wheels. For $65,000, we estimated, someone can buy a new weatherized RV trailer with kitchenette, bathroom, climate control, and new dedicated plumbing and electric lines on a new gravel pad. Add in rental operating costs, and it would only need to bring in $464 per month on almost any Portland lot with much of a backyard.

Is a 250-square foot RV trailer, even a nice new one, “housing”? That’s debatable. Is it a place someone could live? Absolutely. And as of today, it’s by far the cheapest way to create new legal shelter in Portland—including the most exclusive neighborhoods. Using standard federal ratios, that rent would be affordable to someone making just 29 percent of Portland’s median income for a one-person household.

Kol Peterson, a Portland-based ADU consultant, is so intrigued by that possibility that he and two business partners are launching a “side hustle,” a company called Tiny Hookups, to prepare backyards for homes on wheels. He says most jobs should come to $15,000 or less.

“I think we need to do something to create more lower-cost market-rate housing opportunities within high-cost markets,” Peterson said in an interview Saturday. “And this seems like the most promising approach to date. Much like ADUs, what we’re doing here is taking advantage of really well-located land in an urban area and developing on it. That’s what makes ADUs more affordable than other forms of housing: You don’t have to pay for the land. It’s free dirt.”

3) Flips are out; plexification is in.

As it ages, a house in a desirable area generally faces two possible futures: either it gets a major remodel (and lands back on the market at a much higher price), or it gets torn down and replaced.

I wouldn’t call remodels bad, exactly. But in the big picture, they’re sort of a bummer—they soak up investment and raise average prices without also helping hold down prices citywide by increasing the total number of homes.

These figures suggest that in Portland, major remodels that don’t also add housing will become less common. Assuming a remodel cost of $60 per square foot for a small old house, we estimated that a flipped two-bedroom unit would need to rent for $3,581 (or sell for an equivalently outlandish price). That’s the same cost range as the units in our hypothetical new triplex—except that each triplex home could be brand new and 48 percent larger.

The implication: As Portland’s structures age, small-scale real estate investors are likely to start looking for ways to create new homes rather than their current work of essentially replacing one small cheap house with one small expensive house. (To avoid the economic waste that demolition creates, this might take the form of major additions that “duplexify” a structure.)

Another possibility our numbers point to: remodeling existing homes into group homes. We modeled acquisition of an older 2,500-square-foot home (for $485,300) and then imagined a remodel (at $90 per square foot) into a seven-bedroom shared house with features like secure bedrooms, a two-fridge kitchen, and a large dining area. Using rent ratios for OpenDoor, a startup operating in Portland that manages a few co-living communities like these, we estimated that each bedroom would need to rent for $919 a month.

Co-living isn’t for everyone, but at that price, it’s plausible in Portland today. And thanks to Portland removing the definition of “family” from its zoning code, it’s now officially legal on any lot in town.

4) Affordable sixplex homes will happen only if someone steps up with subsidy.

One great dream of many housing advocates is that if cities allow denser housing, new homes can be cheap enough for poor people to live in immediately after they’re built.

Unfortunately, these figures show why things aren’t that easy. At $200 per square foot—not a princely construction cost these days—each additional 915-square-foot two-bedroom home in a sixplex costs $183,000 to build. One-sixth of the land cost, site work, city fees, and construction of shared spaces like a stairwell comes to another $150,000.

A home that costs $333,000 to create is not going to be naturally cheap. Add in property taxes and operating costs, and the monthly rent would need to be $2,354. That’s almost double the $1,258 that meets the city’s two-bedroom affordability standard for a household earning 60% of Portland’s median income.

But Portland’s new code offers another possibility: charge market rate for half the homes on site and set aside the other half for regulated affordability. So we modeled that. The upshot: the sixplex still couldn’t be built unless the three market-rate homes could rent for $3,450 each—well out of range for a nice two-bedroom in Montavilla.

So, as Sightline and other housing advocates warned when proposing this option in 2019, mixed-income sixplexes at this size probably aren’t going to pop up on their own even if they’re legal. (At least, not until market-rate home prices soar to Vancouver, BC, levels.) They would also need some sort of direct subsidy. That might come from a nonprofit like Habitat for Humanity, which uses charitable support and an unusual structure of double mortgages to finance homes more cheaply. Or it could come from the public.

If the government were to chip in $150,000 for each of the affordable homes—a typical sum in Portland for a new subsidized home—the three market-rate homes would need to rent for something like $2,750. That’s still probably too high to make a project work in Portland today, but it’s not nearly so far out of reach. Depending on the details, such projects might work on some lots.

5) Portland now has a pressure valve if its housing shortage gets worse

This last point might be the single most important thing about Portland’s smallplex legalization.

Allowing big group homes and backyard homes on wheels is about the present. Allowing fourplexes and mixed-income sixplexes is mostly about the future.

Last year in Phoenix, a metro area with a population about twice that of Portland’s, the temperature broke 100 degrees on two of every five days. For more than a month’s worth of days, the temperature broke 110. Across the American West this year, 95 percent of land is experiencing drought. This spring, Oakley, Utah, became one of the first US cities to ban the construction of new homes due to lack of water.

Cascadia will be far from immune to climate change. But it’s hard to imagine that its temperate, water-rich cities won’t continue to appeal to people looking for a relative refuge. And if climate changes within North America and around the world lead Portland’s growth to accelerate, today’s zoning reform will let the city become a welcoming haven to more people, while also shielding its residents from some of the costs.

Today, despite a painful decade of price hikes, almost nobody’s willing to pay $2,478 for a two-bedroom fourplex unit in Montavilla. But if Portland prices were to reach that level—a level they reached long ago in San Francisco, Vancouver and much of Seattle—Portland’s fourplex legalization would swing into action. Hundreds and eventually thousands of those homes could be built at that lower price—each one of them holding a household that would otherwise have been competing with every other household in Portland for the homes that already exist.

If migration accelerated, prices rose, and almost all of Portland were still reserved for single-detached homes, the city would not have this new safety valve on prices. The price pressure would just keep building—and it would fling the Portlanders with the least money out of their homes, out of their neighborhoods, and eventually out of the city.

That is, of course, exactly what has already happened to many Portlanders during the last 97 years.

Zoning reform today can’t undo past harms inflicted on entire communities. But it can be part of a more just future and a more welcoming Portland.

Comments are closed.