After decades of impasse in a thousand city halls, housing advocates are looking to statehouses for zoning reform. Many now think state, provincial, and even federal reforms may pass more easily than local ones.

I don’t think that’s because the politicians who lead larger governments are more likely than local officials to want the zoning reform desperately needed by our society, economy, and planet. It’s because larger-scale zoning reforms might actually be able to deliver a crucial benefit that isolated local efforts can’t: lower home prices.

This is a subtle difference. But I think it’s useful for the pro-housing movement to think about.

States delegated zoning to cities, then failed to oversee them

In his podcast Friday, New York Times reporter Ezra Klein interviewed Vox housing reporter Jerusalem Demsas. As residents of (respectively) Oakland and Washington, DC, both are legally required to be angry about housing policy. Fortunately, both are so smart and well-informed that a great conversation shone through their palpable, understandable rage.

Demsas is of the view that the likeliest path to make housing abundant in job-rich urban areas is to convince state, provincial or federal governments to intervene:

The only power that cities and localities have are the ones that states give them. So everyone keeps talking about this like, ‘Oh, this is a local issue. We can’t intervene here. We can’t do anything about this, because it’s a local issue.’ It’s a local issue because states are deciding it’s local issue. … This is causing widespread economic devastation, and continuing to think of it as a local problem is part of why we’re not solving it.

Sightline shares this view. When cities have been consistently failing to build the housing we need, it’s time for states or provinces to step in and regulate those cities—to assert the state’s power to set basic standards for local zoning.

Why would zoning reforms be likelier to succeed at higher levels?

Klein has a good question for Demsas and the rest of us who share her view: Why do we think zoning reform is going to be any politically easier at the state and federal level?

I’m worried this is the same problem almost at every level of it that you go to. … Gavin Newsom, the governor of California, with the assent of the legislature, could take a bunch of power from L.A. and just go over them. But Gavin Newsom can’t lose the support of L.A, either. …

What I see when I look at California at this point, is a lot of politicians who more or less get what the problem is. But they have not figured out a way around the political opposition to solving it.

Demsas and Klein both say this problem requires “collective action,” and I agree. But I think there’s a more precise way to think about this. If I were a detective like my old TV heroes Hercule Poirot, Jessica Fletcher, and Kima Greggs, I might call it the difference between means and motive.

Many local officials are motivated to end housing shortages—but they know it’s beyond their means

Many local politicians in cities where scarce housing has driven up prices do not care much about the issue. But others do. Just as Klein observes of state-level politicians, most politicians in these places “more or less get what the problem is.”

But they know something else, too. Even the sympathetic politicians know they couldn’t solve the shortage even if they tried.

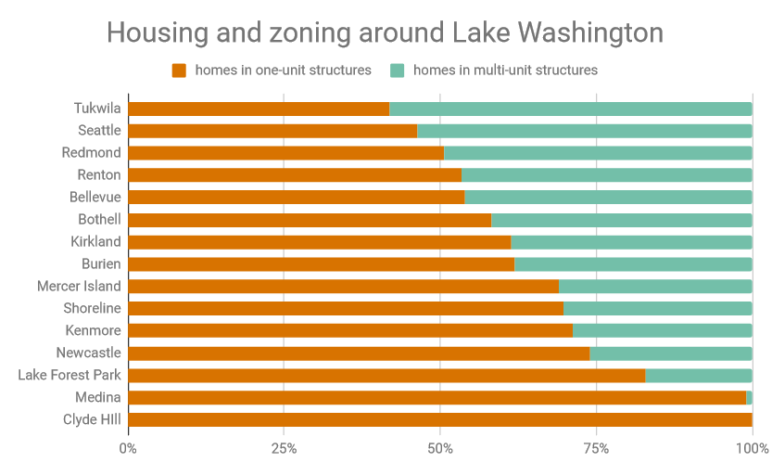

Here is a chart showing the share of housing provided by single-detached homes in each of the municipalities surrounding Lake Washington, immediately east of Seattle. These are some of the highest-priced cities in one of the nation’s most expensive metro areas—a region whose economy was calculated, just this month, to be paying the country’s second-highest “zoning tax” to private landowners.

Source: Census American Community Survey, 2015-2019.

What if the leaders of one of these cities—let’s say Tukwila, population 20,000—were to decide they were going to opt out of the apartment bans that swept into almost every city in the United States and Canada in the mid-1900s? What would happen?

Tukwila’s leaders would have a massive controversy on their hands. Meeting after meeting would be filled with angry homeowners who’d heard about the plan via Facebook and email. If things got really wild, the Seattle Times might even send someone down to write about the whole thing.

Still, the Tukwila City Council could muscle through and re-legalize four-story apartments, fourplexes, and backyard cottages on any residential lot. They could also resolve to dedicate much of their city’s associated property tax windfall to a new housing affordability fund that could use income-based renter assistance, community land trusts, and/or social housing to ensure that anyone who wanted to live in Tukwila could afford to do so.

And if Tukwila’s leaders moved heaven and earth to do all this … it would not be enough.

All their work would be a drop in the bucket of the vast regional housing market.

The garden apartments that would gradually pop up along South 140th Street would do their part to dampen the region-wide housing shortage a bit, just like the similar buildings that created Seattle’s “streetcar suburbs” did in the 1920s. But housing shortages spill across city limits. So the sad truth is that until land itself becomes less expensive in Tukwila—something that will happen only when housing becomes less scarce throughout the Seattle metro area—Tukwila couldn’t end its own housing shortage even if it decided to. The other cities nearby would still control its destiny.

So if you were on the Tukwila City Council, facing a choice between the following:

- a political firestorm that would not solve the problem unless many other cities also faced the same firestorm simultaneously, or

- focusing on other issues instead

…which would you choose?

Local zoning reform is good, but few cities can deliver the biggest prize – abundant housing

To be fair, local zoning reform does have local benefits. If apartments were legal throughout Tukwila, the land along Tukwila’s bus lines might gradually get the shops and homes that boost bus ridership, creating a self-reinforcing cycle of better transportation. The city’s tax base would probably grow significantly. Individual Tukwilans would likely have a better range of options for housing that’s right for them in any given neighborhood, even if prices stayed high.

Also, things are different in a much larger city like Seattle. Unlike its smaller suburbs, it has enough low-density land to put a big dent in a regional housing shortage. (Heck, north Seattle alone has enough land to hold one of the best-loved cities on the planet: Paris.) Legalizing apartments throughout Seattle, even if it happened nowhere else, would probably improve the lives of most Seattlites. And in fact, the general concept of ending single-family zoning is nearly a consensus issue in Seattle’s current mayoral race.

But in most cities, the big prize that many politicians in job-rich areas would love to deliver—an end to ever-soaring home prices—is beyond the reach of local control. The city council has the motive to act, but it lacks the means to succeed. So, though in some jurisdictions it’s possible to convince sympathetic elected officials to tackle zoning, it’s easy to understand why so few do.

State-led reform is hard too, but it’s worth pursuing

California Senate President Pro Tem Toni Atkins has backed several state-led zoning reforms including Senate Bill 9, a middle housing legalization up for a vote in 2021. Image by Gage Skidmore used under CC BY-SA 2.0.

At the state level, things are somewhat different. This month, Louis Mirante of California YIMBY wrote that a massive zoning reform bill his employer had backed in 2019 and 2020 had been popular “because it was the first time many people saw a legislator propose a meaningful end to their housing struggles.”

That bill, SB 50, failed. As Demsas and Klein say in their conversation, state and federal action is no picnic, either. But as recent victories in Oregon, California, and Connecticut show, winning is possible. And, unlike in many local settings, state politicians who win the battles for zoning reform have a better shot at getting the results their constituents want.

“My constituents are experiencing the impacts of the lack of housing every single day, and it is not getting better because we are not doing things differently,” said Democratic state Rep. Jessica Bateman in an interview Monday. “Every year in Thurston County we fall further and further behind the number of units we need to keep up with population growth. That trend line needs to change.”

At any level, zoning reform “takes a lot of work,” said Bateman, who previously helped oversee major local zoning reforms while sitting on the Olympia City Council. Since joining the legislature, she has fought for state-level reforms like House Bill 1157, which nearly became law this spring.

“It’s my hope that we’ll be able to look at this issue boldly and holistically next session,” Bateman said. “Advocates really should be focusing their efforts on the biggest return for their time and energy. And we need to hear from advocates.”

jessica

My boyfriend and I of 11 years cannot be together in Washington state because i am on section 8 and hes not supposed to be here more than 10 calender days a year. Any chance this will ever change? This has ruined my life i dont make enough to get out of housing i am on disability.