Takeaways

Washington lawmakers passed a bill to cap most climate pollution in the Evergreen State.

This legislation is the culmination of more than a decade of effort by Governor Jay Inslee, state lawmakers, and advocates.

The program is well-designed, learning from some of the missteps that California made.

It complements the many other climate and clean energy policies state lawmakers have passed, particularly in the past two years.

Eight years into Jay Inslee’s tenure, he finally signed a bill capping statewide climate pollution. The Climate Commitment Act (CCA), or SB-5126, passed the Senate by a 27-22 vote with one day left in the legislative session. The bill implements the most aggressive statewide cap and invest system in the nation, and will be a critical tool to meet Washington’s recently updated emissions reduction targets.

Many variations of pollution caps and taxes have come up to the legislature in the last decade. In 2014, Governor Jay Inslee put forth a robust cap and invest plan. Republicans shut it down. In 2015, he tried using executive power. A judge shut it down. Then came Initiative 732 (I-732), a pollution tax proposal that split the environmental community. It didn’t make it past the voters. In 2017, a total of four climate pollution tax proposals were floated in the legislature. Not one made it out of committee. In 2018, another tax bill was introduced but was a few votes shy of making it out of the Senate. In November 2018, Initiative 1631(I-1631)—a pollution tax proposal supported by a broad coalition of social justice groups, environmentalists and labor interests—failed at the ballot box.

That failure caused climate hawks to retrench and spend 2019 and 2020 passing an impressive suite of bills requiring carbon-free electricity by 2045, energy efficiency in commercial buildings, phasing out hydrofluorocarbons, funding vehicle electrification, requiring greater a greater percentage of cars and trucks sold in the state to be zero-emissions, and tightening the state’s previously lax greenhouse gas emissions goals to reach net zero by 2050.

In 2021, lawmakers were ready to try passing a “polluters pay” bill again. Senator Reuven Carlyle, who chairs the Senate Environment, Energy & Technology Committee, introduced the Climate Commitment Act and won support from fellow legislators and from a wide array of advocates and business interests. They succeeded, vaulting Washington state to national leadership on climate action!

What changed this year?

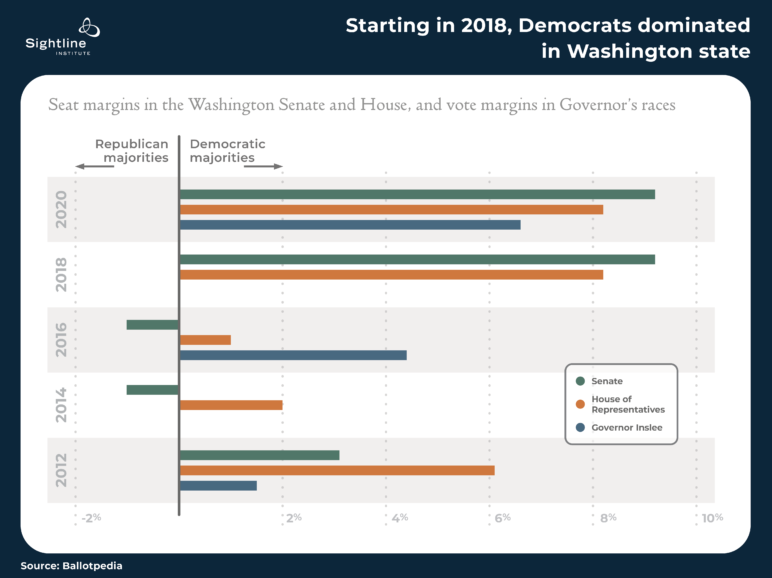

David Roberts, an energy and politics reporter, advises that the “one weird trick can help any state or city pass clean energy policy” is to elect more Democrats. Washington proved him right. Voters gave climate hawk Jay Inslee an increasingly clear mandate with each successive election, while flipping the state Senate from red to blue in 2018 and dramatically increasing the Democratic margin in the House from a tenuous 50-48 to a whopping 57-41. The result? Elected Democrats got to work. Climate and clean energy bills stopped rolling back down the hill each session and started making it over the top. Hence the impressive list of bills passed since they took control in 2019.

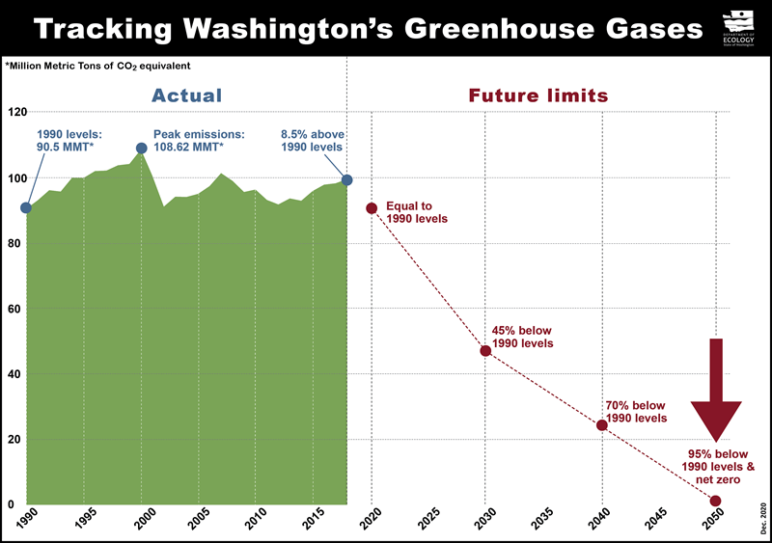

Lawmakers clearly hear the clock ticking. Since Inslee’s time in office, statewide emissions have continued to rise in the absence of any carbon pricing mechanism, rising 8 percent since 2012, putting pressure on lawmakers. “We have to get to five million metric tons by 2050, that’s the fruit. We have got to go from a hundred million metric tons in 2018 to five million metric tons by 2050. And the only way we’re going to do that is a ferocious attack on carbon emission reductions by individual sectors, as well as economy-wide,” said Senator Carlyle about the steeper carbon reduction targets adopted in the 2020 session.

Lawmakers clearly hear the clock ticking. Since Inslee’s time in office, statewide emissions have continued to rise in the absence of any carbon pricing mechanism, rising 8 percent since 2012, putting pressure on lawmakers.

Carlyle credits this year’s success to a combination of policy, politics, timing, and momentum. The empowered Democratic majority in Olympia built on and added to the movement that had formed around past ballot initiatives. Most of the environmental and social justice groups, tribes, and others who worked to pass previous ballot measures also supported the Climate Commitment Act (minus racial equity groups Got Green, Puget Sound Sage, and Front and Centered). New partners jumped in to support the Climate Commitment Act, including the Jamestown S’Kallam and Snoqualamie Tribes, Washington Black Lives Matter Alliance, the Build Back Black Alliance, the Washington Business Alliance, and Northwest Gas Association. In a stunning reversal, BP Oil, facing increased pressure from shareholders and consumers as well as proliferating climate lawsuits, went from spending $13 million against Initiative 1631 in 2018 to funding a public relations campaign in support of the Climate Commitment Act through the organization Clean and Prosperous Washington.

But where past ballot efforts centered around advocacy groups negotiating amongst themselves, the action this year was state lawmakers negotiating with each other, listening to advocates, and getting the bill across the finish line.

How does cap and invest work?

The Washington State Department of Ecology will set a declining cap on the amount of pollution allowed each year, in accordance with the state’s emission reduction goals. To enforce that cap, it will create tradable allowances worth one metric ton of emission, and only release allowances equal to the cap. Entities that emit more than 25,000 metric tons per year must obtain allowances equal to their emissions, either directly from the department or by purchasing allowances in a quarterly auction run by the State. If they pollute more than they have allowances for, they must pay harsh penalties. This ensures that pollution declines on the timeline the state has committed to.

Cap: How much pollution will it eliminate?

Washington now has appropriately aggressive pollution goals in place, aimed at ensuring the Evergreen State does its part towards a stable climate. The cap will reduce pollution to the goal line shown in the graph above. Within a few years, the cap will cover emissions from transportation, electricity, natural gas, and industry: 75 to 80 percent of all emissions in Washington. The cap is enforced through allowances: emitting entities must hold allowances equal to their pollution or face severe penalties. The state only creates the number of allowances equal to the cap, ensuring statewide pollution will not exceed the cap.

Invest: What will the revenue be used for?

The state will raise money from auctioning off allowances, and will invest that money in creating a green and just economy in Washington. State agencies estimate that revenue from auctioning off allowances will top $450 million in the market’s first year of operation in 2023, rising to nearly $600 million by 2040. The actual revenue amount will depend on the auction price (see more below) so the numbers below are estimates, but the money will be invested roughly as follows:

- Transportation Decarbonization. By far the most money is directed to the Carbon Emissions Reduction Account, which aims to decarbonize the transportation sector. That means alternatives to single occupancy vehicles, alternative fuel infrastructure, and programs for freight and ferries. Highway projects under the 18th Amendment are specifically prohibited from using these funds. A specified amount of about $360 million per year, which works out to about 70 to 80 percent of expected revenue, goes into this account until 2037. After 2037, this account switches from a fixed amount to a percentage: 50 percent of all revenue, expected to be around $250 million per year.

- Air Quality Monitoring. Every two years, $20 million will go to the Air Quality and Health Disparities Account, which will fund an air quality monitoring network in communities overburdened with air pollution.

- Tribal relocation and pollution reduction. Of the revenue remaining after transportation and air quality investments, 75 percent will go into the Climate Commitment Account. Of that, $50 million every two years will go to relocate tribal communities in danger of rising sea levels or flood risk. The remainder, probably around $30 million in early years, rising to around $150 million per year after 2040, will fund climate mitigation projects such as reducing air pollutants in overburdened communities and deploying renewable energy resources.

- Ecosystem resilience. The remaining revenue, approximately $18 million in early years, rising to around $60 million per year after 2040, will go into the Natural Climate Solutions Account, which aims to increase habitat resilience for vital ecosystems across the state. The exact amount invested each year is 25 percent of the revenue remaining after the transportation and air quality investments.

When administering funds or grants from any of these accounts, agencies must conduct an Environmental Justice Assessment and ensure a minimum of 35 percent, with a goal of 40 percent, of investments provide direct benefits for vulnerable populations in overburdened communities. Another 10 percent minimum will go to projects supported by tribal resolution.

How much will allowances cost?

The price of allowances will be determined in each quarterly auction and will depend on how cheap or expensive it is to reduce pollution and build a clean energy economy. But the policy has a little bit of certainty built in: a rising floor and a rising ceiling price for the quarterly auction will contain prices in a predictable range. Prices still need to be adopted by the Department of Ecology, but revenue estimates are based on California’s floor price starting at $20.60 per ton in 2023 and increasing seven percent each year. At that rate, the minimum allowance price in 2050 will be $134. The price ceiling would likely also follow California’s, start at $74.81 per ton in 2023, increasing five percent per year plus inflation to a maximum price of $246.75 in 2040 and $497.72 in 2050. However, if the state gets off-track in its pollution reductions for some reason, the Department of Ecology will review the program in 2027, 2035, 2040, and 2050 and revise rules as needed to get the state back on track.

How are allowances allocated?

The state will provide free allowances to emitters in several categories of industry:

- Electric utilities are provided free allowances under the Clean Energy Transformation Act, passed in 2019, so utilities will not have any allowance costs to pass on to customers. If a utility reduces emissions below their free allowance level and ends of with excess allowances, they will auction those and return the proceeds to customers, prioritizing low-income customers.

- Natural gas utilities get free allowances equal to their baseline emissions then declining 6.5 percent per year consistent with the declining cap. Of these free allowances, 65 percent to start and increasing five percent annually until it reaches 100 percent, must be co-signed at auction and the proceeds used to benefit customers. Low-income customers must see no rate increases due to allowance costs.

- Manufacturing companies that are determined to be vulnerable to out-of-state competition if exposed to higher prices will be classified as emissions-intensive trade-exposed (EITE) companies. They will initially receive no cost allowances equal to their baseline for the first compliance period, with slight decreases in following periods.

All others must purchase allowances in a state-run quarterly auction.

How does it address environmental justice?

Advocates for environmental and racial justice are in complete agreement that we must tackle climate change, but split over how to go about it. Tribes, Black Lives Matter Alliance, and Build Back Black Alliance all supported the Climate Commitment Act, while Front and Centered, Got Green, and Puget Sound Sage opposed the Act because they oppose the tradable allowances that are used to enforce pollution limits in a cap and invest system. Those groups supported I-1631’s tax and invest approach. (Both a cap and a tax hold large polluters accountable by making them pay for every ton of pollution they emit. Both have their benefits and shortfalls. A tax is simpler to administer but does not guarantee pollution reductions. A cap requires more administration, such as auctioning and tracking allowances, but guarantees overall pollution reductions. Both could allow certain facilities to simply pay more and continue to pollute, but that is a greater risk with a tax, which only requires payment whereas a cap requires reductions.)

Advocates worked to ensure legislators built in environmental justice protections in several ways.

Participation. The people most impacted by pollution often don’t have much voice in the halls of power. This year, lawmakers made an attempt to remedy that by passing the HEAL Act, a bill backed by social justice groups and aimed at giving the people most harmed by pollution a path to push state agencies to address their needs. The act requires seven departments (Agriculture, Commerce, Ecology, Heath, Natural Resources, Transportation, and the Puget Sound Partnership) to prioritize work that reduces harm to communities hit hardest by pollution. The HEAL Act also creates a 12-member Environmental Justice Council, drawn from affected communities and state agencies, to advise on the work. The Governor-appointed Council will also advise on the development and implementation of the cap and disbursement of funds.

Air quality. A primary concern for environmental justice advocates is the local air pollution that usually comes along with climate pollution. As the Washington Environmental Health Disparities Map illustrates, neighborhoods with more people of color and poor residents also often experience more exposure to pollution. A cap guarantees overall pollution reductions, but doesn’t guarantee reductions in any particular neighborhood, which could lead to the same patterns of pollution persisting.

The Climate Commitment Act addresses local pollution disparities head-on by identifying pollution-burdened communities, and then requiring clean air agencies to do whatever it takes to reduce air pollution in those communities. Some environmental justice advocates point out that even when a policy reduces air pollution relative to what it used to be, burdened neighborhoods might still experience worse air relative to wealthier or whiter neighborhoods in the area. In other words, for places with more poor and people of color, better than before can still be worse than other neighborhoods. The Climate Commitment Act takes that on, too. It requires agencies to ensure air quality in overburdened communities either meets federal air quality standards, or is as good as nearby communities, whichever is cleaner. Since all of Washington currently meets federal standards, this provision will have the effect of reducing disparities by ensuring that burdened communities enjoy air as clean as their luckier neighbors.

Every two years, the Department of Ecology will conduct an Environmental Justice Review to ensure the cap and invest program is achieving reductions in pollutants in overburdened neighborhoods. The Environmental Justice Council, established in the HEAL Act, will review agency reports to ensure progress is being made toward those goals.

Investments

Some of the allowance revenue is earmarked for air quality monitoring, to ensure agencies have the data they need to carry out their mandate of cleaning up the air in overburdened communities.

In addition, as mentioned above, 35 percent or more of investments must provide direct benefits for vulnerable populations in overburdened communities. Another 10 percent minimum will go to projects supported by tribal resolution.

Protections

First Europe and then California have shown us how too many allowances and too many (or low quality) offsets can undermine the cap, dragging down air pollution benefits, too. Washington learned from its predecessors’ mistakes, creating a tighter cap and restrictions on offsets.

Will Washington link with California and Quebec?

The bill was written with the intention of being able to hook into the Western Climate Initiative, California and Quebec’s linked cap and invest system. According to Senator Carlyle, the ability to link is essential to the long-term success of an economy-wide cap. “We have the luxury of going second,” he said about the structural improvements the CCA made compared to California.

Before Washington can combine markets with any other system, the Department of Ecology will need to evaluate whether unused allowances in a linked program would reduce Washington’s ability to meet its emissions limits. The Climate commitment Act also requires that a linked jurisdiction must ensure that benefits of the program are benefiting overburdened communities and the agreement would not adversely impact either jurisdiction’s vulnerable populations. This may be a tall order given that Washington has done California one better in terms of its emissions limits and environmental justice benefits.

California continues to suffer from an oversupply of allowances, weakening the cap and potentially making it a liability for Washington to link and risk undermining its own cap. Another area in which Washington is stricter than California? Offsets. Offsets are a credit for reducing emissions from a source outside the cap, often agriculture or forestry, that regulated entities can use in place of an allowance. The use of offsets in California’s system allows companies to pollute and then purchase offsets to get back into compliance, shifting the air quality benefits from their local neighborhood to wherever the offset came from. Offsets are big business and have been found to systematically overvalue emissions savings. An analysis by Carbon Plan found that nearly 30 percent of offsets are over-credited, to a value of $410 million. The New Republic reported last week about BP’s financial stake in the offset developer Finite Carbon.

In the CCA, offsets are limited to cover up to eight percent of an entity’s compliance obligations during the first compliance period and reduces to six percent afterwards, with projects on tribal lands contributing three and two percent, respectively. The offset projects are intended to be used locally, with 50 percent of projects being in Washington state through 2026, then 75 percent after that. However, unlike in California, offsets will be “under the cap.” In essence, the Department of Ecology will determine the amount of allowances offered with offsets in mind so that together they will add up to the emissions cap. This prevents the cap being busted by low quality offsets. In addition, the Department of Ecology can restrict the use of offsets to specific entities if they are found to be a contributor to air pollution in overburdened communities. The combination of the broad under-the-cap accounting and precision of eliminating offsets for specific entities are both major improvements over California’s system.

What’s next?

Implementing the CCA was conditional on the passage of a transportation package, but Governor Inslee used his line-item veto to sever that link, saying he hopes to call a special session in September for legislators to work out a transportation funding deal. As vehicles increase in fuel efficiency, gas tax revenue per vehicle has declined. The package would have included a five cent per gallon increase in the gas tax to stem some of the projected loss of $1.9 Billion in revenue over the next decade. The transportation package has been criticized for spending heavily on highways rather than public transit, but it is partly constrained by Washington’s state constitutional requirement that gas tax revenue be used for road projects. Which is why lawmakers coupled it with the Climate Commitment Act, which will put more than $5 billion towards transportation decarbonization in coming years. Transportation emissions are by far the largest sector, contributing nearly 45 percent to in-state emissions in 2018.

Washington got its climate act together

It took longer than climate warriors hoped, but Washington lawmakers have put together a first-in-the-nation package of climate action policies to be proud of. Now the challenge is for agencies to implement the policies well, and for the Evergreen State to show other states what it looks like to reduce climate pollution while creating a just, sustainable, healthy economy.

Deep gratitude to Catie Gould for her help researching and writing this article.