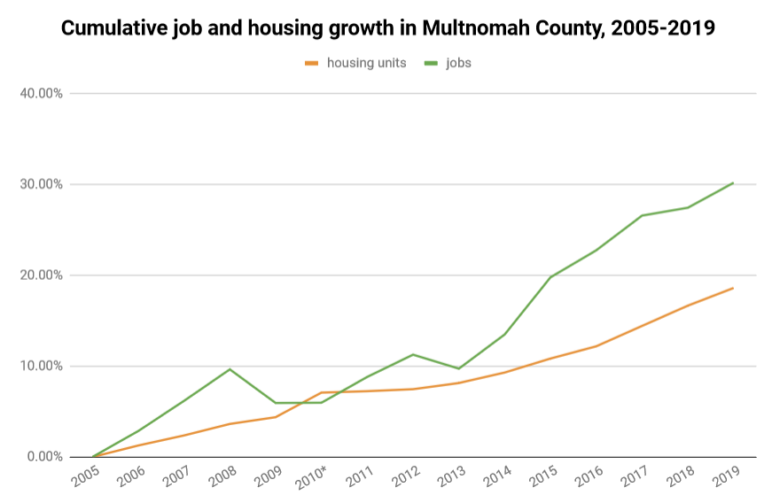

It’s happened again and again and again in Portland throughout the Cascadian city’s recent housing crisis. For one big project, it’s been happening since the second Obama administration.

Someone proposes to build some apartments. Some people who own homes nearby dislike some aspect of the plan. They look for any leverage they may have over the process—and if it happens to be in the parts of Portland where the city regulates how new buildings are allowed to look, they argue that something is wrong with how the building would look.

“The city is so desperate for housing that it’s sacrificing the integrity of our city,” Stanley Penkin, a New York City native who bought his newly built Pearl District condo in 2016 for $866,603, told Willamette Week in a memorable 2018 article about the trend. “Is it just build, build, build to the maximum at any cost?”

Penkin and his neighbors ended up losing their legal challenge to the Fremont Tower, a 17-story apartment building slightly downhill from the 28-story condo building they live in. The new 17-story building is finally in construction now. Meanwhile, Penkin continues to chair the Pearl District Neighborhood Association, and the 275 households who might have lived downhill from him if the Fremont Tower existed by now have instead been competing with every other Portlander for the housing that does exist.

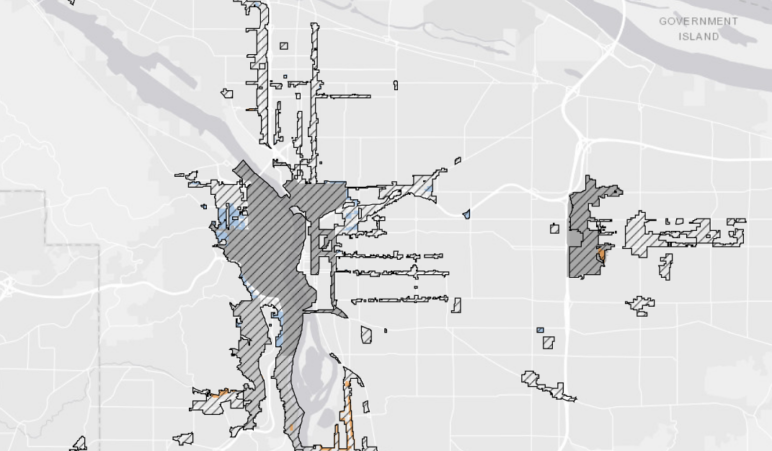

Next week, Portland’s city council is considering a proposal that could permanently lock into many other parts of Portland the system that let Penkin and his neighbors challenge the existence of the Fremont Tower.

Appeals don’t often kill a project – but the risk of appeals can

Most projects within Portland’s so-called “design overlay” are never appealed. Virtually all of those that do face rejections or appeals ultimately win, though winning an appeal isn’t always enough to save a project with a financing deadline.

To understand why the win/loss ratio isn’t the whole story, consider the case of Slabtown Square.

When the mixed-income, mixed-use apartment project on Northwest 21st Avenue was first proposed in 2015, the plan looked like this:

Neighborhood association representatives had pushed hard for a European-style central square, but didn’t like that the only way to fit it in while also building the homes that would fund its existence was for the project to encroach on the public walkway just east of the building. So the developer scrapped that plan and came back in 2017 with this proposal instead:

The city’s design staff declared this version “substantially improved,” and the Design Commission signed off. But this approach didn’t please a determined group of nearby residents who felt the privately funded plaza associated with the building didn’t fit the bill the city had once promised. The Northwest District Association tied the project up in a string of unsuccessful appeals—first to Portland’s city council, then to the state’s Land Use Board of Appeals, then to the state court of appeals, and finally to the Oregon Supreme Court, which sealed the case in 2020 by declining to hear it.

Slabtown Square hasn’t opened yet. Neither has the publicly funded park that has, for four years now, been scheduled to open next door.

Would an investor with shallower pockets or a less well-connected architecture firm have stuck with the project? Would they have proposed it in the first place, knowing that such a string of appeals would be possible? It’s impossible to say.

One thing is certain. Despite all that hassle, the City of Portland is hoping that more people will be willing to keep proposing homes in Slabtown. The longtime industrial area is one of just a few neighborhoods outside Portland’s officially designated “central city” where it’s not illegal to build a seven-story apartment building.

If something about Slabtown Square’s six-year journey to construction gives an investor pause, and other homes in the area never get built, the effect will be the same as for any structures that go unbuilt. The hundreds of mostly well-off people who would have lived in them will instead find themselves in a big, cruel game of musical chairs, competing against every other Portlander for whatever homes are allowed to exist.

Housing projects are 20 times more likely than other projects to face design appeals

None of this is to argue that well-designed buildings are bad. They are good. Portland’s Design Commission consists of respected local professionals who are fully aware of the need for their work to improve projects without accidentally killing them.

When this system works well, it is a much smaller burden on new projects than, for example, the city’s long permitting timeline.

The risk, though, is that the system may be exploited, either in the form of obstructive appeals or threats by critics of the project who can credibly afford to appeal. Such threats create leverage, whether or not those critics ever follow through with a formal appeal.

But if we look specifically at the appeal rate, data released Friday by the Portland Bureau of Development Services shows that in the last eight years, design-regulated housing projects in Portland have received design appeals from the public at 20 times the rate of non-housing projects: 8 percent vs. 0.4 percent.

The issue here isn’t just that something like 1 in 12 housing projects can expect to face appeal from the public. It’s that Portland’s design appeal process is already being applied disproportionately to new housing.

If design appeal rights become permanent in homeowner-dominated areas, will they get more common?

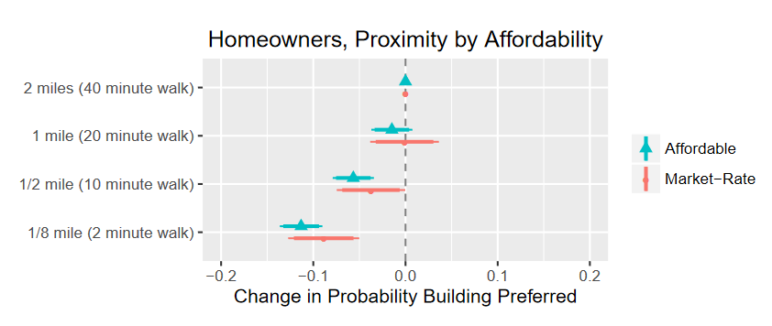

Why do some projects draw more opposition, and more legal challenges, than others? The answer may have something to do with the raw number of nearby homeowners.

A national survey of 3,019 adults, published in 2017 by Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies, found a clear trend. The closer a proposed apartment building is to the place a homeowner lives, the likelier they are to oppose its existence.

As the blue lines on the chart above show, this tends to be even more true of affordable housing than market-rate housing. But as the red lines show, it’s true of every project.

As with any polling trend, this doesn’t describe the opinion of every homeowner. And only a tiny share of homeowners will be willing to go so far as to legally challenge a project, or threaten to do so—especially if legal challenges aren’t a local norm.

But every homeowner near a new project presumably creates a small additional risk of appeal.

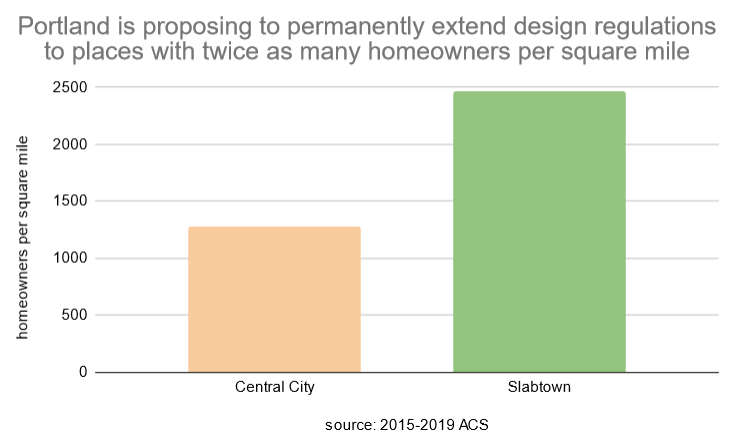

In most of Portland’s central city—where the appeal-vulnerable design review process has long been used—there are very few homeowners per acre. But it’s a different story outside downtown, where the city is proposing to start applying its design regulations.

In the two census tracts that include Slabtown and are mostly zoned for seven-story buildings, homeowners are twice as common as in the central city.

Supporters of permanently expanding the design review system into Slabtown and elsewhere, like David Keltner of Hacker Architects, don’t see this as a problem. They argue that because relatively few housing projects have been appealed in the past, and because those that do face appeals almost always win, the design review process must not be a meaningful barrier to new housing—and will not become one, even if it’s permanently expanded into neighborhoods with less urban atmosphere and many more homeowners.

“There has never been a case where a NIMBY neighborhood appealed a project to design review and had it shut down,” Keltner argued last month. “This proposal is not about affordable housing. It is an effort to remove a process a specific group of architects and developers are bad at.”

Other local architects disagree. They say it’s the threat of appeal and delay, not the final ruling itself, that creates unnecessary burdens on housing—and also on entry to their profession.

“Without an objective path to approval, our system rewards architects who are good at the process, not necessarily those who can deliver the greatest design,” wrote Sam Stuckey. “The architecture field is already one of great inequity and I am disappointed that so many of my colleagues are more interested in maintaining their relationship with the current system, rather than supporting new paths to participation in the design of our city.”

Objective standards could let Portland regulate mid-rise buildings in a new way

Early in this article, I said Portland’s city council will vote next week on a proposal to permanently expand its appeal-vulnerable design review process to more of the city—specifically to many of the onetime streetcar corridors that extend through seas of pricey detached homes. (Generally beloved commercial corridors whose buildings were, of course, constructed mostly in the early 1900s without any design regulations.)

Happily, Portland’s council has an opportunity to rethink its design regulation—a modern process developed with downtown skyscrapers in mind—for low-rise and mid-rise neighborhoods.

The city’s staff, Planning and Sustainability Commission, and Design Commission have spent five years working out a set of “design standards”—a LEED-style point system—that are designed to push developers toward interesting-looking buildings without also sending every project through the unpredictable, appeal-vulnerable Design Commission review.

The “design standards” option wouldn’t replace discretionary design review; any project could opt for the discretionary process if a builder wants to do something more creative. But having the new points system as a viable option would fulfill Oregon’s statewide mandate to offer a “clear and objective” path to taking advantage of a site’s zoning.

Last year, Portland’s planning commission unanimously voted to apply the standards to low-rise and mid-rise buildings—up to 75 feet in height, or about seven stories.

Taller structures, with their unique visibility, inherently deeper-pocketed investors and longer timelines, would still need to use the discretionary process.

Portland’s “point system” for regulating design has promise

Last month, Sightline joined a coalition of below-market housing developers, mixed-income housing developers, architecture firms, and advocacy organizations to urge the city to “ensure that this straightforward point system is an option for the vast majority of new projects outside the central city.”

Nick Sauvie, executive director of ROSE Community Development in outer southeast Portland, was one of many affordable housing providers working in Portland who signed the letter urging both market-rate and below-market housing to be able to use the objective point system in almost all situations. He warned that mandating the appeal-vulnerable discretionary process for buildings less than 75 feet “will lead to more projects killed, delayed, and made more expensive.”

If the point system for mid-rise buildings works, it might be usefully applied in other cities, too. Seattle has expanded its own discretionary, appeal-vulnerable design review system to many neighborhoods; a series of subsequent efforts to rethink the system have been unsuccessful.

“What you want is to eliminate your risk that you have around design review and the cost of it,” said Maria Barrientos, a Seattle-based apartment developer who said a single round of her city’s design review process generally adds about $250,000 to $300,000 to the total cost of a new building. “If there’s a list you can pick and choose and manage around, that’s a known thing.”

Objective standards can prevent bad design, but nothing can guarantee good design

Ben Schonberger, a senior planner with Portland-based Winterbrook Planning, said that in his observation, the uncertainty of the subjective Design Commission review process leads most builders to avoid it if they can.

“If you are savvy and skilled, you aren’t afraid of design review and can build that into your schedule,” said Schonberger, who also sits on the board of the housing affordability advocacy group Housing Land Advocates. “But we need all kinds of developers, not just those who are willing to go through the pain of design review.”

Objective design standards and subjective Design Commission review can both have a useful role, Schonberger said: “raising the floor” of urban design by ensuring that the very worst buildings don’t go in.

Objective standards alone, he said, can steer projects away from common problems: “Your building isn’t going to have blank walls, your building isn’t going to turn its back on the street, your building is going to have some articulation.”

But Schonberger said he doubted that either subjective Design Commission review or objective design standards will ever lead to more truly excellent buildings.

“What makes incredible buildings are passionate, interested, well-capitalized builders,” Schonberger said. “It’s just like any business—there are good ones and there are bad ones. If they’re not really interested in appearance, it’s going to be crappy no matter how many times you go through the design review process.”