State lawmakers have had mixed reaction to the record-high voter turnout in 2020. Some Republicans, egged on by Donald Trump’s Big Lie, have panicked at the specter of millions of Americans voting and introduced bills aimed at throttling those voters back. Other state lawmakers, mostly Democrats but with a few Republicans joining in, are attempting to keep voters engaged by implementing best practice for protecting voting rights.

Georgia has become the poster child for the efforts to restrict voting. Voters in the Peach State chose Democrats Joe Biden, Kamala Harris, Raphael Warnock, and Jon Ossof in statewide votes. But Republicans hold 58 percent of the seats in the state legislature. In a party-line vote, state Republicans passed a bill that will make it harder for eligible voters to vote. They claim to be protecting against (non-existent) voter fraud, but that’s not what the bill does; rather, it is designed to make it harder for eligible voters to vote, especially in Democrat-dominated urban areas. Florida Republicans followed suit, and more than 300 bills are pending in other states.

That is bad news for voters, and for American democracy.

But there is good news! Some state lawmakers want to build on the successful voter turnout in 2020 and have introduced more than 700 bills to make it easier for eligible voters to vote. These bills are mostly sponsored by Democrats, but there are some Republicans fighting on the side of democracy.

The bills hit on many different aspects of voting rights, so we’ve taken a deep dive into a few policies that are important for making voting easy and secure.

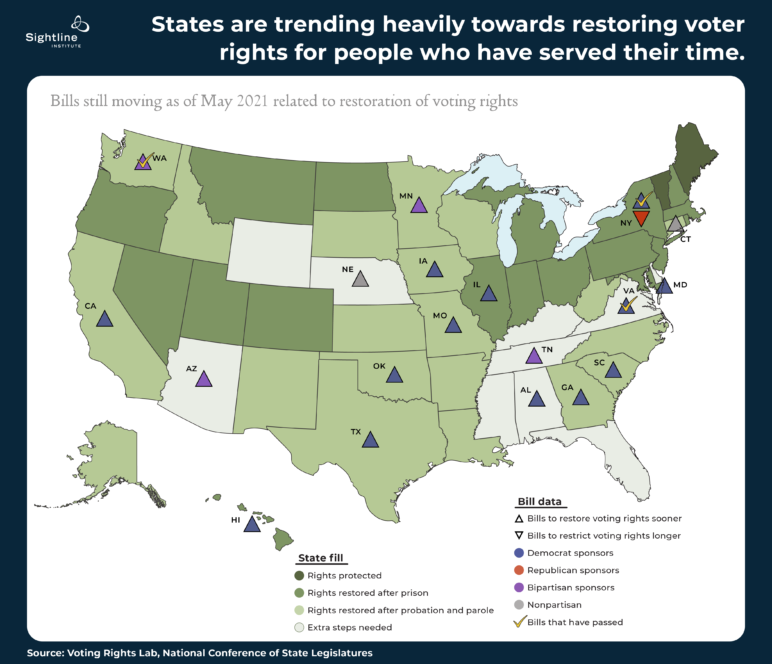

Rights Restoration

After the Civil War, former Confederate states were forced to acknowledge that Black men were now allowed to vote. But the 14th Amendment had a loophole. It allowed states to deny people the right to vote for “participation in rebellion or other crime.” Some states exploited this loophole by taking voting rights away from people convicted of even minor crimes. For example, a Florida man lost his right to vote because he released a dozen heart-shaped helium balloons to celebrate his girlfriend on Valentine’s Day. Once lost, some states make it difficult or impossible to get the right to vote back. Even when a person has served their time in prison, completed their probation, and completed their parole, they may have to jump through additional hoops if they ever hope to vote (gray states in the map below).

Recent polls show that around 60 or 70 percent of Americans think that, once someone has served their time in prison, they should be able to vote again. Legislators in 24 states, including five states with bi-partisan support (Arizona, Kentucky, Minnesota, Tennessee, and Washington), introduced bills moving in that direction, and bills are still moving in 18 states (upward triangles in map below). Washington, Virginia and New York have all passed bills automatically restoring rights upon release from prison (gold check marks in the map). Only New York Republicans are contemplating moving backwards on this issue (red down triangle), and only for a very specific sliver of people: the bill would prevent sex offenders who have served their time from voting for the duration of their institutionalization if they are committed to a hospital after serving their prison sentence.

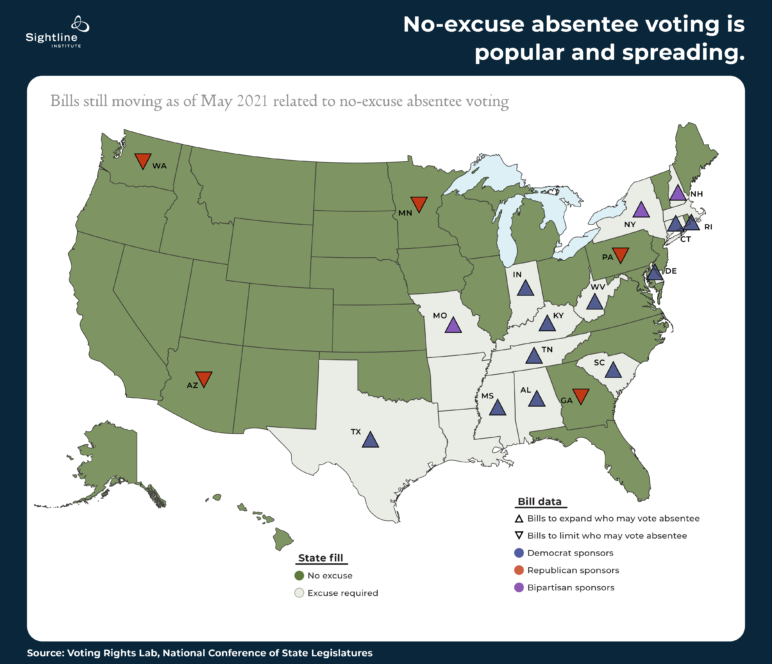

No-Excuse Absentee Voting

No-Excuse Absentee Voting

Most states allow any voter to request to vote absentee (green in the map below). Only a few holdouts in the southern and northeastern parts of the country still demand that voters provide an excuse for wanting an absentee ballot (gray states, below). That could soon change. Only a handful of Republican lawmakers are trying to add an excuse requirement in their states (down triangles). But in 14 of the 16 states still requiring an excuse, lawmakers have introduced bills to allow any registered voter to request an absentee ballot. As of May 2021, all those bills are alive (up triangles).

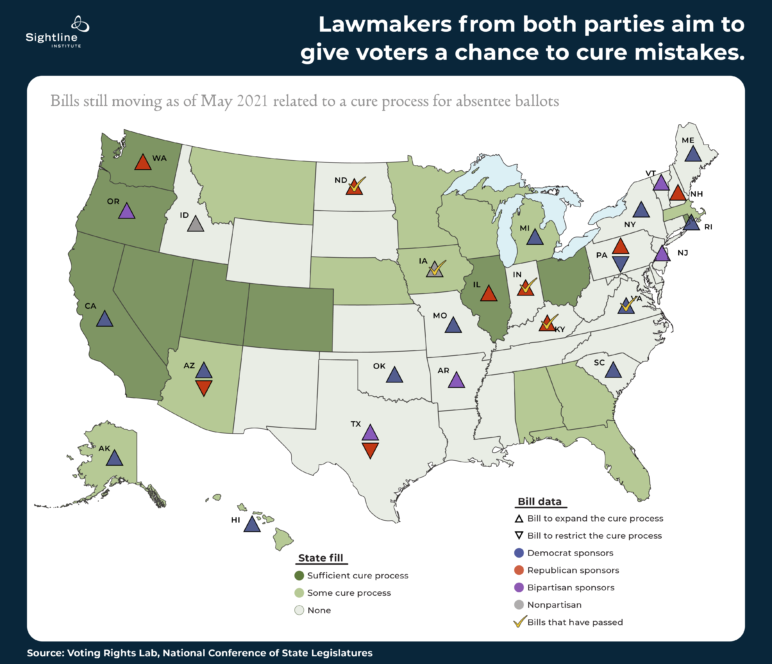

Cure Process

Cure Process

If a voter forgets to sign their ballot return envelope, or if their signature doesn’t match the one(s) on file, they deserve the chance to correct, or cure, the error and have their vote count. Nineteen states have laws requiring clerks to notify voters if there is a problem with their signature and then give voters an opportunity to cure. Some states (darker green in the map below) allow sufficient time—three business days after Election Day—to cure, while others (lighter green in the map below) allow less. The remaining states simply toss these ballots, giving voters no chance to get their vote counted (gray states).

Voters see the fairness in having a chance to stop their vote getting thrown out on a technicality: 63 percent support a sufficient cure process. Lawmakers see the value too. Legislators, including quite a few Republicans, have introduced bills in 33 states to create or improve the cure process, and bills are still moving in 26 of those (up triangles in map below). Only in Arizona, Nevada, Pennsylvania, and Texas are lawmakers contemplating making it harder to fix ballot errors (down triangles). Pennsylvania belies the usual partisan pattern: the Keystone State previously had an exact signature match requirement and no cure process, but in 2020 the League of Women Voters litigated on behalf of voters and won a ruling that said officials needed more reason to throw out a ballot. State Republicans are seeking to re-instate the exact match requirement, but add a cure process so that voters at least have a chance to correct a problem with their signature. Lawmakers in North Dakota, Kentucky, Iowa, Indiana, and Virginia have passed laws improving their cure process. No state has passed a bill reducing the opportunity to cure.

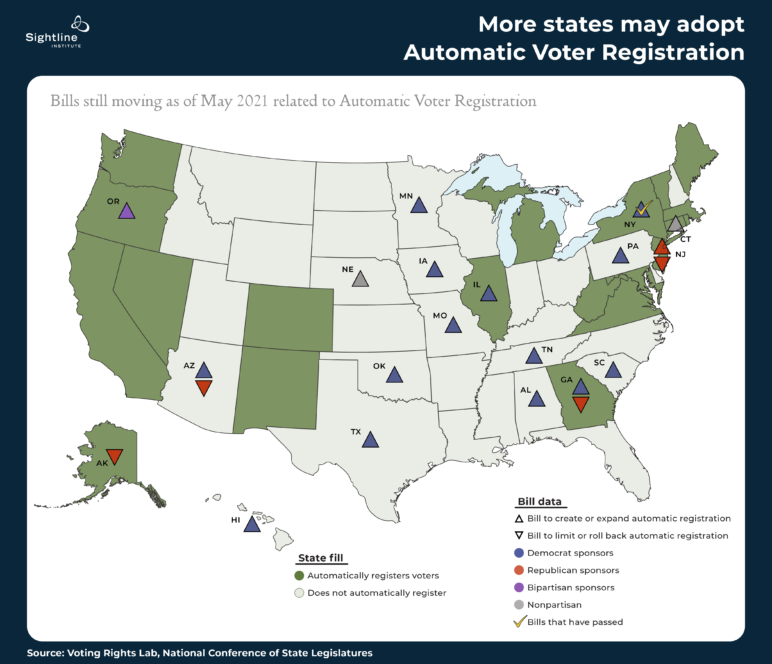

Automatic Voter Registration

Automatic Voter Registration

Nineteen states plus DC (green, in the map below) use a secure and modern process for keeping their voter lists up-to-date. When someone proves their citizenship to a government agency, that agency digitally transfers their information to the agency in charge of maintaining voter lists, so that new eligible voters can be added to the list and existing voters’ records will be updated with their most recent address. This system is easier for voters, because they don’t have to register and re-register, and it’s more efficient and secure for election officials who can be confident that they lists are accurate.

A recent poll found that 73 percent of Americans support automatic voter registration, and another poll found 61 percent support. State lawmakers seem to understand it is popular: only six states introduced bills to roll it back, and bills are still live in four of those (downward triangles in the map below), while 24 introduced bills to create or expand it, and bills are still alive in 18 of those (upward triangles in the map below). Oregon, New Mexico, Georgia, New Jersey, and Connecticut all use Automatic Voter Registration but have pending bills to expand the data used to add and update eligible voters’ information. New York already passed a bill to add State University of New York information to the data it uses.

Single Sign-up

Single Sign-up

Eighteen states plus DC (green in the map below) give some or all voters a “single-sign-up” option. In five all Vote By Mail states, eligible voters receive a ballot every election; in other states, a voter must fill out an application for an absentee ballot just once and then will continue receiving a ballot in the mail each election without further paperwork. In states without all Vote By Mail, voters must repeatedly fill out—and election officials must repeatedly process—absentee applications. The extra paperwork isn’t just a burden on voters. It’s a financial burden on election administrators who may spend eight times as much money processing absentee ballots without the single sign-up policy.

The double enticement of cost savings and voter ease may be why 20 states have introduced bills to offer or expand a single sign-up option, and as of May, bills are still alive in 18 states (upward triangles). Maryland passed a bill allowing any voter to sign up to permanently vote absentee, and Virginia will automatically move all special absentee voters to a permanent list this year. Meanwhile, only lawmakers in Arizona, North Dakota, Minnesota and New Jersey are even considered taking it away (downward triangles) but so far only the Arizona bill, removing voters from the single-signup list if they skip a few elections, has passed (gold check mark).

Ballot Tracking

Ballot Tracking

Comprehensive ballot tracking uses intelligent barcodes to track every ballot and envelope, minimizing the risk of stolen ballots or ones that have been tampered with. It also increases transparency and accountability, because voters can easily track when their ballot is in transit, arrived at their residence, received by election officials, and counted. This boosts voter confidence as they know exactly where their ballot is. And it increases security and efficiency, because election officials know how many ballots are on the way to be counted.

Ten states require ballot tracking and 30 others have some form of ballot tracking, though not required by statute. Voters love ballot tracking to the tune of 83 percent support.

Lawmakers from both sides of the aisle in nine states are entertaining bills to improve ballot tracking (upward triangles). Utah has passed a bill requiring comprehensive ballot tracking (gold check mark).

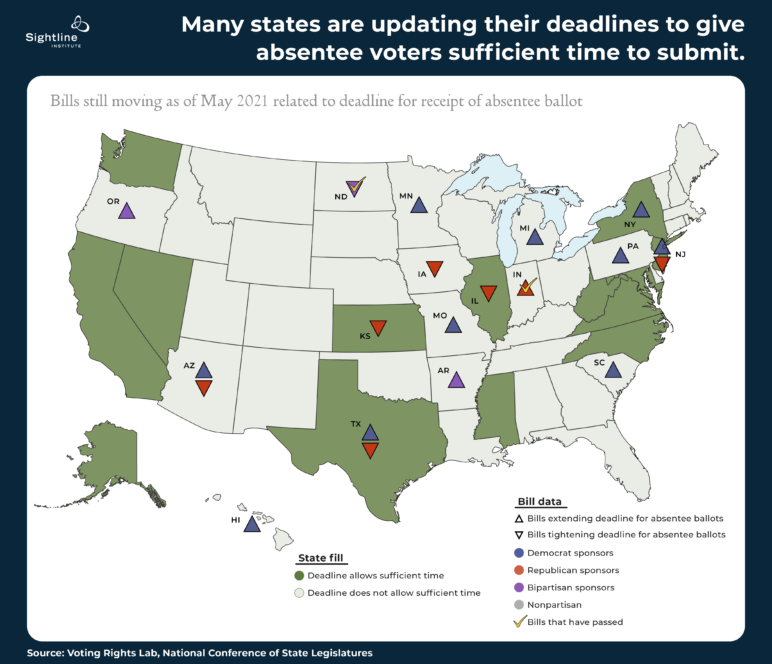

Deadline to Receive Absentee Ballot

Deadline to Receive Absentee Ballot

You can’t control the mail. But 32 states expect voters to get their ballot in the mail with enough lead time to ensure it arrives at the election office on or before Election Day (gray states in the map below). Later-arriving ballots, even if clearly postmarked by Election Day, get thrown out. This strikes many voters as unfair—60 percent oppose the practice of rejecting ballots mailed before Election Day that arrive later. Many states are trying to bring their rules more in-line with voter expectations.

Eighteen states introduced, and 13 are still considering, bills to extend the deadline for receiving ballots mailed by Election Day (upward triangles). Indiana passed a bill to extend the deadline in counties that use e-poll books from noon to 6:00pm on Election Day. Only eight states introduced, and seven are still considering, bills to make voters get their ballot in the mail even sooner than Election Day (downward triangles).

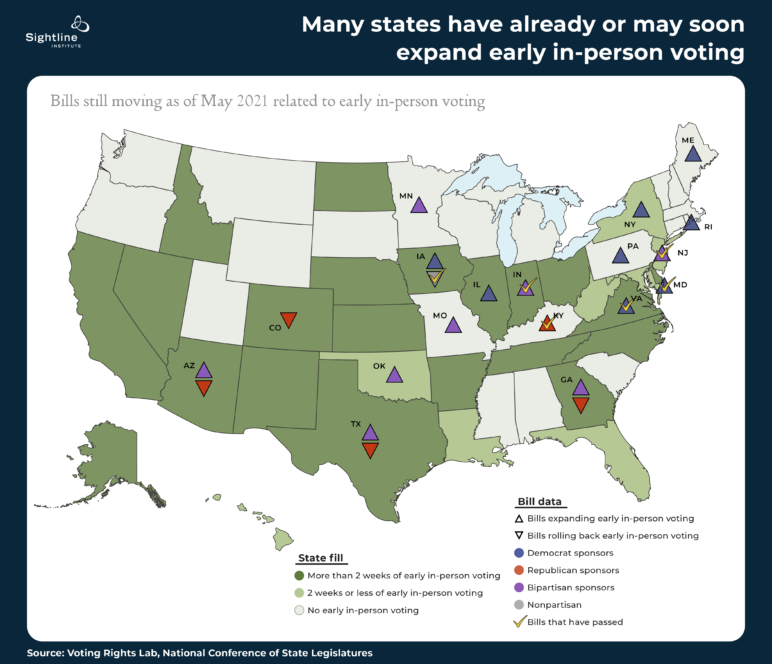

Early In-Person Voting

Early In-Person Voting

Many people have work schedules and family obligations that make it difficult to vote on a Tuesday. That’s no doubt why early in-person voting is wildly popular. Pew finds that 78 percent of Americans overall, including 63 percent of Republicans, support it. Early voting doesn’t just work for voters’ schedules, it also makes it less likely that voters who do show up on Election Day will encounter long lines, because some of the crowd has been thinned in the days leading up to Election Day. Twenty-one states offer more than two weeks (darker green in the map below), sufficient to make sure that voters can find a time to vote. Another eight states offer two weeks or less of early voting days (lighter green states). Twenty-one states don’t offer any early voting (gray states).

Many state lawmakers are responding to their voters. Lawmakers in 20 states introduced bills to create or expand early voting, and bills are still alive in 17 of those (up triangles). Indiana, Kentucky, Virginia, Maryland and New Jersey already passed bills expanding early in-person voting (gold check marks). Iowa passed a bill reducing the number of in-person early voting from 29 to 20 days, and restrictive bills are still alive in Arizona, Colorado, Texas, and Georgia (down triangles).

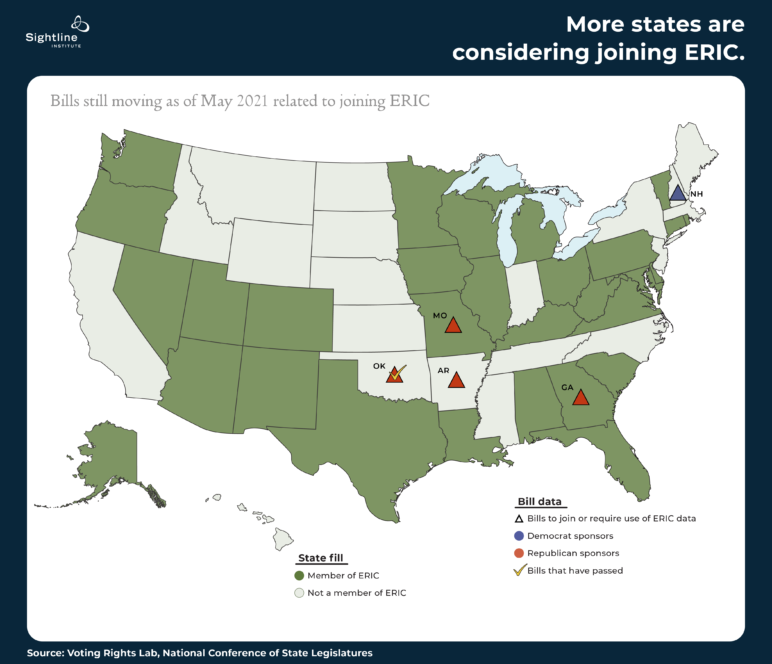

Electronic Information Registration Center

Electronic Information Registration Center

Election officials’ best defense against any possible voter fraud is clean voter rolls. If there are no dead people, duplicates, or nonresidents on the rolls, then only eligible voters can vote. Thirty states and DC are using best available technology for keeping their lists clean and accurate. They are members of the Electronic Registration Information Center (ERIC), which helps them identify any outdated or invalid voter registrations. ERIC compares voter records to multiple databases, such as the US Postal Service change of address and social security deaths databases, and reports to each member state which voters may have moved within the state, moved out of the state, passed away, have duplicate registrations, or may be eligible to vote but have not yet registered. States can then update addresses, remove deceased or duplicate voters from the rolls, and reach out to eligible voters to encourage them to register.

Oklahoma has passed a bill to join ERIC, while Arkansas and New Hampshire have pending bills to join ERIC. Georgia and Missouri are already members but using ERIC data is optional, so they have pending bills to make it mandatory.

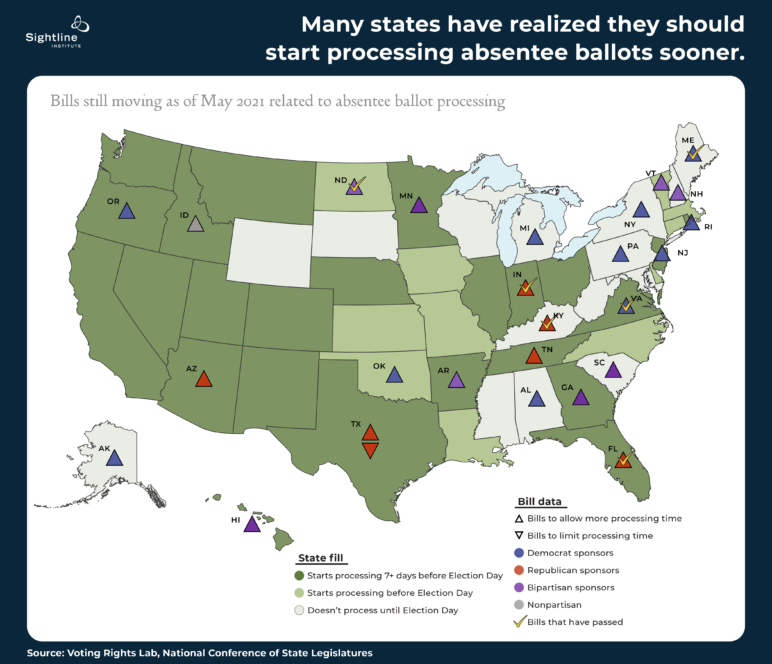

Start Processing Absentee Ballots

Start Processing Absentee Ballots

Election administrators need to process absentee ballots before they can tabulate the votes. Processing ballots involves verifying the voter’s identity, sorting and opening envelopes, and preparing ballots for tabulation. All this can occur before Election Day so that the actual day-of tabulation can go as quickly as possible. Spreading the workload like this may also save money by reducing the number of scanning machines needed, since by starting earlier, each machine will have more time to count ballots. Some machines are capable of shielding results until a specified day and time so that officials can start vote tabulation before Election Day without anyone seeing the results. Sixty-five percent of Americans think election officials should be allowed to being processing absentee ballots before Election Day.

In 26 states (darker green in the map below), state law allows election administrators to start processing envelopes upon receipt or at least seven days before Election Day, giving officials enough time to have a good start on processing ballot envelopes before tabulation starts. Another seven states allow processing to begin a few days before Election Day but don’t give officials quite enough time (lighter green states). Fifteen states require election workers to sit on their hands until Election Day, and then have a mad rush to process (gray states).

State lawmakers in 29 states introduced bills this session, and bills are still moving in 26 states, to give election officials more breathing room and let them start processing sooner (up triangles). Bills improving processing time have already passed in Indiana, Kentucky, Virginia, Maine, and Florida. Only Texan lawmakers are contemplating making it harder on election workers (down triangle).

Pre-paid postage on return envelopes

Pre-paid postage on return envelopes

Providing prepaid return postage for absentee ballots makes voting easier and can improve voter turnout because voters can focus on voting, not on locating stamps, weighing their ballot, or going to the post office to find out how much mailing the ballot will cost (which can vary from one stamp to three First-Class stamps, depending on the weight of the ballot). Prepaid return postage costs around $0.80 per voter. Voters get that this makes their life easier, which is why 73 percent support it.

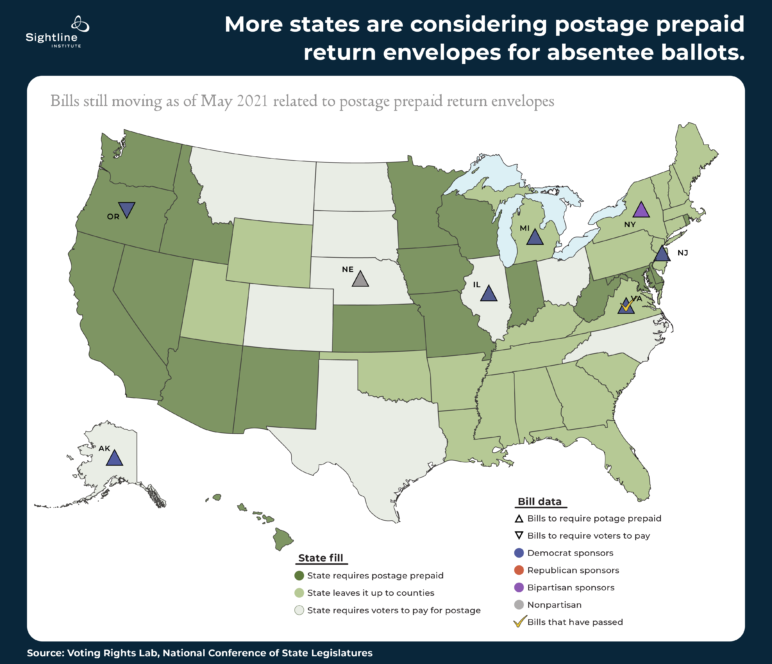

In 17 states, election officials provide envelopes with prepaid return postage for absentee ballots (dark green in the map below). In 22 states, county officials may decide whether they will pay for return postage (light green). Ten states prohibit election officials from providing pre-paid envelopes (gray states).

Lawmakers in nine states introduced bills to offer pre-paid postage. Bills are still alive in Alaska, Illinois, Michigan, Nebraska, New Jersey, and New York. Virginians passed a bill (gold check mark), so absentee voters will receive postage prepaid return envelopes starting with the November 2021 election.

Some good news

Some good news

It’s true that Republican lawmakers across the country are doubling down on the idea that hurting voters will help their own electoral chances. But it’s also true that states are passing bills to make it easier to vote, from expanding early in-person voting hours to improving the vote by mail process. When legislative sessions have ended, voters in Georgia, Florida, and Texas may see more barriers to the ballot box. But voters elsewhere may see improvement in their access to voting. And as more states make it more accessible and also more secure, those trying to hold back the tides of voters will find themselves increasingly out of step with 21st century democracy.

Deep gratitude to the Voting Rights Lab for the database this work is based on, and to Sarah Johns for wrangling all the data.

No-Excuse Absentee Voting

No-Excuse Absentee Voting Cure Process

Cure Process Automatic Voter Registration

Automatic Voter Registration Single Sign-up

Single Sign-up Ballot Tracking

Ballot Tracking Early In-Person Voting

Early In-Person Voting Electronic Information Registration Center

Electronic Information Registration Center Start Processing Absentee Ballots

Start Processing Absentee Ballots Pre-paid postage on return envelopes

Pre-paid postage on return envelopes Some good news

Some good news