Strange as it may seem in a country that might be headed for double-digit home price hikes in the next two years, many US cities make it illegal for groups of people to share big houses.

But that will no longer be the case in Oregon. On Monday, that state’s Senate approved House Bill 2583 by a 27-0 vote, with three absences, sending a bipartisan law to the governor’s desk that’ll strike local definitions of “family” out of zoning codes. Local codes will no longer dictate who does and doesn’t count as “related”—and, therefore, how many supposedly “unrelated” people are legally allowed to share a home. Instead, cities will simply apply uniform fire safety standards when deciding whether a group of people who want to share a home should be allowed to. The bill’s lead sponsor was Representative Julie Fahey, who chairs the Housing Committee of the state House of Representatives.

The Oregon bill’s passage follows victory for a similar bill in Washington just last month. Iowa passed another in 2017, also with bipartisan support. State courts in California, Michigan, New Jersey, and New York have struck down local limits on so-called “unrelated occupants” under their existing laws and constitutions.

Momentum for similar reforms seems to be growing at the local level, too. Last week, Portland’s city council unanimously approved its “Shelter to Housing Continuum Project,” which did the same thing, among many other things, for Cascadia’s third-largest city. (It’s worth noting that some cities like Tigard, a close-in suburb of Portland, never imposed such limits in the first place.)

Another bill nearing approval in Oregon, House Bill 2534, would hold private homeowners’ associations to the same standard as local governments. That bill would strike limits on “unrelated” individuals, along with other discriminatory measures, from HOA covenants.

An essentially Unanimous reform

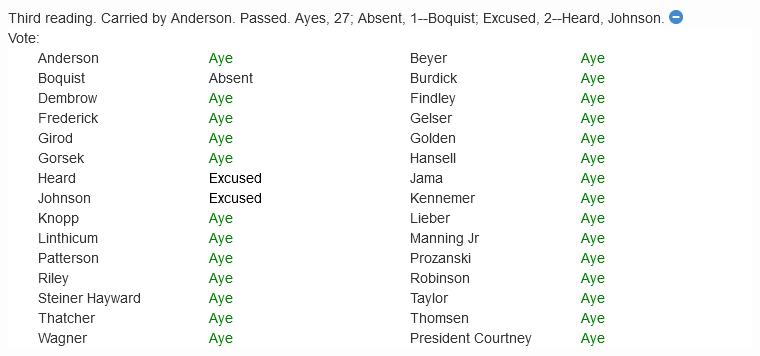

Roll call vote on HB 2583 in the Oregon Senate. Source: Oregon Legislative Information System.

House Bill 2583 didn’t find much opposition in Oregon’s state legislature.

The League of Oregon Cities, which two years before had fought hard and lost against state-led fourplex legalization, didn’t take sides on the bill once an amendment had allowed for fire-safety limits on household occupancy. State senator Dick Anderson, a first-term Republican who had previously served as mayor of Lincoln City on the state’s affordable-housing-starved Pacific coast, took the baton from Fahey and a bipartisan crew of other legislators to carry it through the Senate.

My colleague Nisma Gabobe, who led Sightline’s advocacy for similar bills in Washington, demonstrated last year that outdated unrelated occupancy rules are a real issue for housing choices. She found at least 162 cities in Washington that imposed these occupancy limits discriminating against people who want to save money, build community, or simply live with those they consider their family even though a city law does not. She was building on 2013 work by Sightline’s Alan Durning, who included outdated “roommate bans” in his roundup of laws that make particular affordable living arrangements and environmentally beneficial lifestyles illegal.

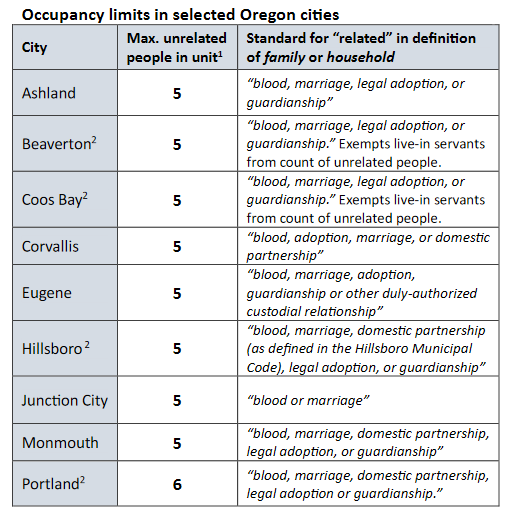

This year, Representative Fahey’s legislative team built further on that work by looking at similar limits in cities across Oregon:

Source: Office of Rep. Julie Fahey, via Oregon Legislative Information Site.

(Beaverton and Ashland don’t count domestic partners as “related” to one another? Junction City doesn’t count adopted children? Again, strange but apparently true.)

As I wrote in February, Oregon’s largest source of under-occupied housing is its 1.5 million empty bedrooms. If House Bill 2583 could turn even one in 100 of those into a residence, it would create 15,000 homes. That was the approximate number of Oregonians without homes as of 2019, according to the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Housemate limits are selectively enforced; that’s part of the problem

In addition to legalizing the obvious Living Single-style “housemates” scenario, bills like 2583 make it legal for two larger families to go in together on a home.

“In my community we’ve got a lot of immigrant families that come together to rent a house together—they’re not all related,” said state Senator Marko Liias, the lead sponsor of the Washington bill, during a hearing in Olympia this year. “If they can do that in a safe way, we shouldn’t have arbitrary limits that say just because you’ve got two families you can’t rent that house.”

Housemate bans aren’t tightly enforced, of course. But it’s exactly because they’re typically complaint-driven—in other words, they’re selectively enforced—that they can become discriminatory. Some people sharing a home might draw more attention simply because they seem different from other households in a neighborhood.

“The LGBTQ community makes our own diverse families through both blood and affinity, and it’s important that our laws reflect this,” wrote Nancy Haque, executive director of Basic Rights Oregon, in a letter of support for HB 2583.

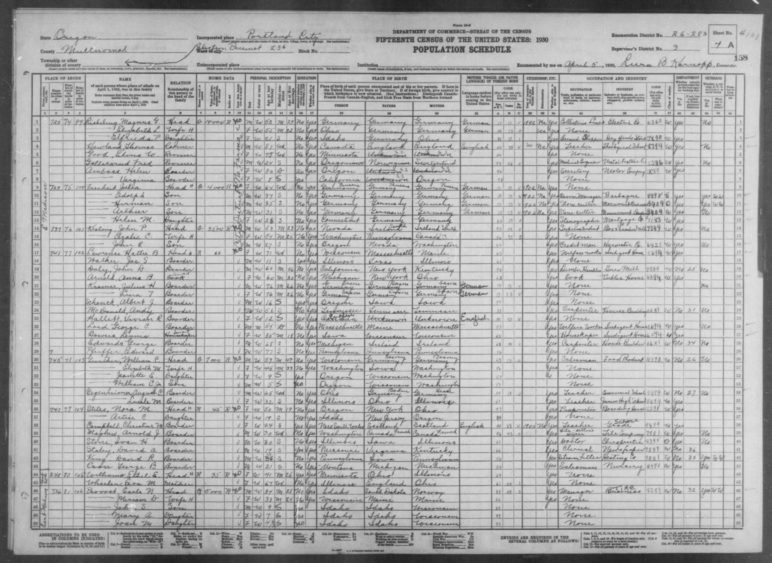

Another great promise of bills like 2583 is that by bringing so-called “co-housing” out of a legal gray area, it’ll let people who own big under-occupied homes turn them into legitimate small businesses, operating as group homes. That’s how millions of Americans housed themselves during the Great Depression:

A data sheet from the 1930 US Census, on Madison Street in inner Southeast Portland. Out of 50 residents listed at eight addresses, 22 were identified as a “boarder” or “roomer.” Image via Gerson Robboy.

Of course, there are other obstacles to letting shared homes become widespread again. As Nisma pointed out last month, there are many other forms of exclusion in our zoning codes and many other injustices in our system of deciding who gets housed and who doesn’t.

But like other varieties of zoning reform, making it legal for people to live together if they want to makes every other housing problem a little easier to solve. It’s great that both Oregon and Washington have now set an example for how to take this step.

Donna

Wonderful!