If the government pays hundreds of millions of dollars to help build and operate a high-quality transit line, people should generally be allowed to live near it if they want to.

You’d think this would be uncontroversial. Especially among people who run public transit agencies.

Unfortunately, some transit leaders here in Oregon seem to be distracted by the exciting goal of building high-capacity bus and rail lines, or at least of dreaming about building them. Instead, they need to face the facts about who will get to ride their buses and trains if walkable, mixed-income neighborhoods are illegal near their future stations.

The truth is that any time a city bans apartments near something desirable—near excellent public transit, for example—it makes gentrification mandatory. When the only things people are allowed to build in a desirable location are low-density homes, then those low-density homes are going to get more and more expensive. Once in a while, an old low-density home might even be replaced by a brand-new, super-expensive low-density home.

An Oregon bill that’s up for a committee vote on Thursday would take modest steps to help more people of different incomes live near high-quality transit if they want to. House Bill 2558 would focus specifically on areas within about three blocks of “high-capacity transit” stations—which is to say, rail like the Portland area’s MAX and WES, and bus lines with dedicated lanes like in Eugene and Springfield’s EmX.

This is an extremely modest housing-near-transit bill

On land zoned for housing within one-eighth of a mile of a high-capacity transit station, the bill would strike down local bans on buildings that create up to 45 homes per net acre. In other words, it would legalize three-story attached housing within about three blocks of these stations:

The three-story Belmont Dairy Townhomes in Southeast Portland, pictured at left, have just a bit less than 45 homes per acre. A bill before Oregon’s legislature would strike down bans on such homes within three blocks of high-capacity transit. Image: Google Street View.

Buildings could be a little taller, probably four stories in most cases, if they house people with a wider range of incomes. This one-floor bonus would go to projects with at least 10 percent of homes affordable to households earning 60 percent of their area’s median income, or at least 20 percent affordable to people earning 80 percent of the median. These mixed-income buildings within three blocks of major transit stations might look more like this:

A four-story building in central Beaverton. Image: Google Street View.

Finally, there’s a provision for greater flexibility: jurisdictions can also opt to keep lower density at some stops and legalize five to six story buildings at other stops, if they prefer, as long as they achieve the same overall density within the 1/8-mile station areas.

Endorsing the bill in February (though urging it to go further), Tyler Mac Innis of the Welcome Home Coalition wrote that legalizing apartments near transit “with strong affordable housing provisions can help Oregon address its housing crisis while making progress on its climate goals.”

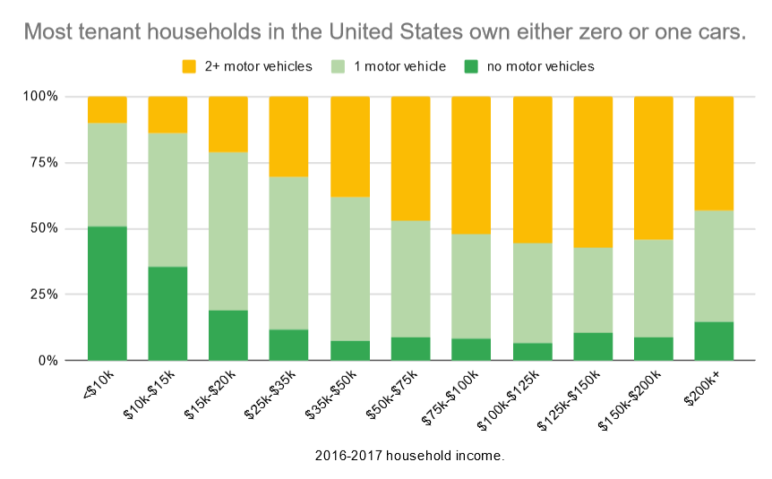

The bill would also make on-site parking fully optional near such transit stations. This wouldn’t block the construction of parking in any way, but it would acknowledge that in a state where about 17 percent of tenant households don’t own a car (it’s currently 19 percent in Eugene, 16 percent in Springfield, 16 percent in Medford, 13 percent in Hillsboro, and 6 percent even in exurban Sherwood), there are at least a handful of places where those people shouldn’t be required by city law to pay for parking spaces they won’t need.

HB 2558 would follow on Oregon’s middle housing model code, approved last year, and acknowledge that when you have to choose between homes for those who don’t own cars and convenient curbside parking for those who do, homes are more important. (At least within three blocks of major transit stations.)

Data: 2017 National Household Transportation Survey.

The two main arguments against this bill cannot both be true, and both are bad

Most individuals who’ve submitted testimony on House Bill 2558 like it.

“Oh yes please!” wrote Matt Cleinman, a tenant advocate who said he stumbled across the bill while preparing to testify on a proposed eviction reform, HB 2372, that was scheduled for the same hearing. “One way to increase affordability is to allow more unit[s] and more people to live close to wonderful transportation options. This is a way of forcing the issue, without NIMBY folks fighting block-by-block to keep areas near transit stop[s] full of large 1-family homes.”

“Families would like to live in accessibility-rich neighborhoods, but cost pushes them to neighborhoods further away and increases vehicle miles traveled,” wrote Rebecca Lewis, a planning professor at the University of Oregon, summarizing her research on Oregon housing preferences.

But (aside from a handful of arguments from homeowners who oppose new housing) the bill has seen two major lines of attack.

- These apartments will be legalized anyway. Cities like Eugene, Springfield, and Hillsboro have argued that they can be trusted to legalize more housing near future transit lines, so there is no reason for the state to require them to do so.

- Legalizing apartments is so unpopular that it will undermine support for public transit. Transit agencies including Lane Transit District and Rogue Valley Transit have argued that if homeowners in low-density areas know that new bus rapid transit lines will come with apartments, those homeowners will oppose the new transit lines.

These arguments are mutually exclusive. Either it is politically easy to lift local bans on transit-oriented apartments, or it is politically difficult. If it is easy, then the transit agencies won’t have the trouble they predict when they expand their bus lines. If lifting local bans on apartments is difficult, then the cities are making promises they may not be able to keep.

Here’s the truth: it can be politically difficult to legalize apartments near transit. But it is necessary. A new transit station that would serve few people—especially few people without other mobility options—doesn’t deserve public funding in the first place.

Yes, HB 2558 would force some arguments to happen. But only arguments that should be happening anyway. If apartments near major new transit stations remain illegal, then precious public transit dollars should instead be going to neighborhoods where they can help more people.

Update 4/12: This bill died in committee on Friday, April 9, after its backers chose not to bring it up for a vote in light of entrenched opposition from the cities of Eugene, Springfield, and the Lane Transit District.

Marian T Gillis

This is another good example of the importance of Zoning. We make it mean many things. But what it means is this.

Local zoning decisions have an international impact on climate. Consider that what we do here, impacts all of us.

Todd Boyle

Thank you for this excellent series on cheaper housing. I am so glad when people use the actual word, “cheap”, because the word “affordable” has been hijacked by the middle housing industry.

Most of the bottom 20% of incomes are already priced out of the market and either paying close to 100% of their income for rent, or surviving in RVs, couch surfing etc. here in Eugene. Many of them would be *THRILLED* to live in a shed for $100/month and since the government has prohibited every kind of actually cheap housing (e.g. Tinies, trailers, RVs etc) in my opinion they are truly an oppressed class.

asdf2

Interesting how, above $125k or so, car ownership actually decreases slightly with income. Assuming this is not statistical noise, the most likely reason is that homes in the walkable neighborhoods that making car-free living easier are very expensive, so you need a lot of income to be able to afford to live there.