It’s happening.

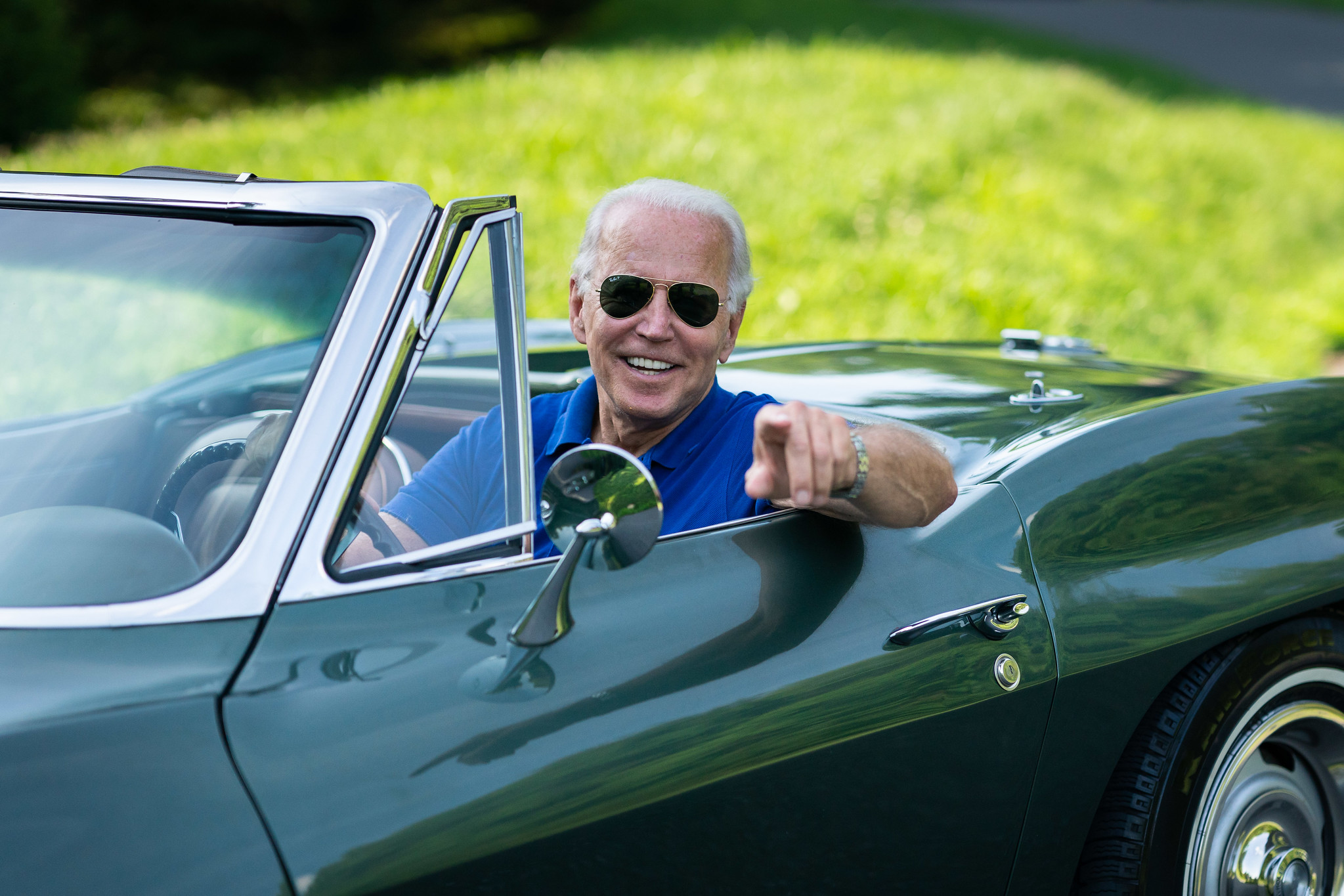

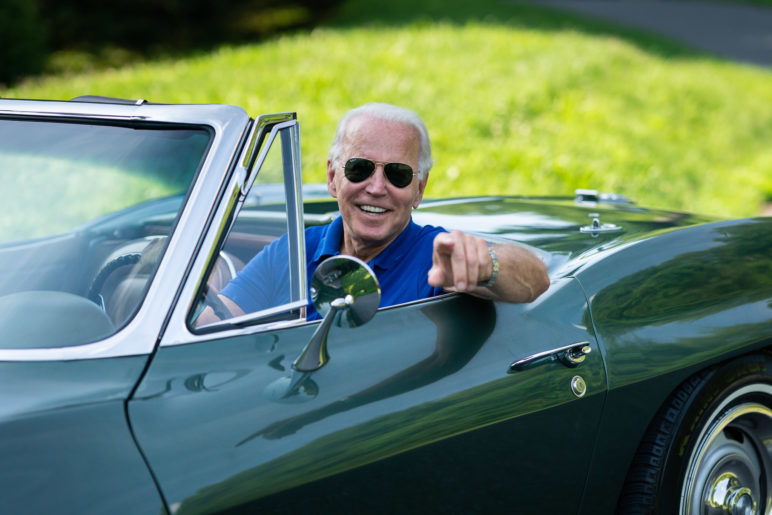

Five years after the Obama White House released a memo endorsing local zoning reforms as a way to fight displacement and boost the economy, three years after the Trump White House did essentially the same, and one year after Donald Trump himself took an interest in the issue long enough to flip-flop on it and spend several ill-fated weeks making the case for neighborhood segregation, US President Joseph Biden endorsed federal legislation to help legalize inexpensive housing.

“For decades, exclusionary zoning laws—like minimum lot sizes, mandatory parking requirements, and prohibitions on multifamily housing—have inflated housing and construction costs and locked families out of areas with more opportunities,” the Biden White House wrote Wednesday in the fact sheet about their infrastructure plan, the American Jobs Act. (Emphasis ours. Because we’re excited.)

Biden’s proposal, which closely resembles the proposed bipartisan Housing Supply and Affordability Act, would create a “new competitive grant program that awards flexible and attractive funding to jurisdictions that take concrete steps to eliminate such needless barriers to producing affordable housing.”

Here at Sightline, that’s music to our ears.

Momentum for zoning reform has been building for years in both major parties

As Sightline’s housing and urbanism director Dan Bertolet wrote last year, “rewarding cities that welcome new neighbors” is “an idea that’s gaining steam.”

Biden’s is a “carrot” based version of this idea. That’s in contrast to Senator Cory Booker and former HUD Secretary Julian Castro, who have proposed limiting transportation grants to jurisdictions with widespread bans on infill housing, and Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, who has proposed stopping all federal highway formula funds to any jurisdictions that ban apartments or mobile homes or impose any parking requirements on housing whatsoever. There’s reason to think either of those approaches would have more effect, and reason to wish for a program that incentivized actual housing production rather than just planning processes.

But that’s politics for you—for better or worse, voters tend to prefer creating new things to taking existing things away. And a “race to the top” approach to zoning reform (as pro-housing analyst Salim Furth of the libertarian Mercatus Center has put it) probably does have the benefit of giving jurisdictions flexibility to find locally acceptable details.

In Minneapolis, legalizing triplexes was a way for higher-price, lower-density neighborhoods to do their part in a broader citywide housing reform. In Austin, mixed-income sixplexes on any lot was a political home run. Here in Portland, the winning formula turned out to be both of those things: smallish market-rate fourplexes on any lot with an option for larger, mixed-income sixplexes.

The Housing Supply and Affordability Act, sponsored by Senator Amy Klobuchar (Democrat of Minnesota), Senator Rob Portman (Republican of Ohio), Representative Lisa Blunt Rochester (Democrat of Delaware), Representative Jaime Herrera Buetler (Republican of southwest Washington) and others, would spend $300 million annually to give federal grants to pay jurisdictions that pursue more zoning reforms like those. The bill would also require policies to “prioritize avoiding displacement.”

In fact, the whole concept is almost identical to the final version of Washington’s own House Bill 1923, sponsored by state Representative Joe Fitzgibbon (Democrat of West Seattle) and passed in 2019 with Sightline’s direct advocacy.

We’re working to help pass a follow-up in Washington State, House Bill 1157, this year. It would take the logical next step and reward jurisdictions when homes actually get built.

State and local reformers are working on this, but they need help

Federal leaders are increasingly looking for ways to push cities to lift bans on homes like these, in a Seattle triplex that was built before the city banned them from low-density zones. Photo by Sightline Institute: Missing Middle Homes Photo Library used under CC BY 2.0

With or without federal action, a wave of zoning reform proposals has been sweeping the nation.

Two months ago, the week of Biden’s inauguration, I wrote this article about reform proposals in Sacramento, California; South Bend, Indiana; Montana; and Massachusetts. Since then, we’ve seen similar measures unveiled and advanced in Tacoma; Northampton, Massachusetts; Berkeley, San Diego, San Jose, and South San Francisco, California; New Hampshire; Connecticut; North Carolina; and (just last night) in Santa Monica, California.

Here at Sightline, we’re particularly optimistic that state-level action (and provincial action, in Canada) can make homes, of all shapes and sizes, more abundant. Housing shortages spill across city borders, after all. Even if one city in a particular region tried to solve its shortage by removing every regulatory barrier to housing, it probably wouldn’t be enough without other cities doing the same. That’s where state lawmakers come in; they have both the motive and the means to address shortages. Oregon and California have been making good progress, but few other states have done much yet. More and more seem to be trying, though.

Removing our bans on duplexes, apartments, and car-free homes is good federal policy and good national politics. It has huge potential to create jobs, reduce displacement, and protect the environment that our long-term economy depends on. It’s great news that the president of the United States is officially interested in it.

Greg

It’s great that it’s being discussed at the federal level but will it really help? It hasn’t so far from either the Trump or Obama administrations. The local level is where all the real obstructions are. NIMBYs have a lot of power in neighborhood councils and city councils, which is where a lot of the decision making lies.

Michael Andersen

Yep, good question!

I agree, the good thing here is that it’s being discussed at the federal level, and so far continues to even be a bipartisan issue. And proposed federal legislation, weak though this is, is a step beyond the dueling executive orders we saw from Obama and Trump.

One thing we can do, at both the federal and state level, is find ways to pull some of that power away from local governments and toward regional and state ones. There’s no inherent reason for power to ban housing types to exist mostly at the local level, and as noted above, there are actually good reasons why it shouldn’t. Federal control is one of the reasons housing policymaking works pretty well in Japan.

DickDeplorable

What business is it of the federal govt to tell states/cities how they can zone their neighborhoods?

It’s just another violation of the 10th Am…..and more evidence Leftists don’t care about the Constitution.

Michael Andersen

Maybe you should reread the paragraph about what the bill does!

RadicalPropertarianLibertarian

What business is it of the State and local governments what I do with my private property? Is it really their role to interfere with my plans to build a quadplex with no parking spaces on land that I own?

Zoe

Two questions–And these are direct quotes from this article–“Here in Portland, the winning formula turned out to be both of those things: smallish market-rate fourplexes on any lot with an option for larger, mixed-income sixplexes.” What is the rationale for calling these new units affordable if they are really market rate?

And another quote–“Removing our bans on duplexes, apartments, and car-free homes is good federal policy and good national politics. It has huge potential to create jobs, reduce displacement, and protect the environment that our long-term economy depends on.” How is demolishing an existing structure and relegating a functioning home to the dump, which consuming new resources to build a new home, good for the environment?

I’m not trying to be argumentative, but I would love to see a study where new market rates homes really somehow translates to affordable, and also a study that shows that demolishing and existing home to build others is an environmental net gain. I hope that these questions are taken seriously, because I seriously am looking for answers, and hope they are out there.

Michael Andersen

Totally fair questions! The short answers, including links to longer answers:

1) On prices: There is near-universal academic consensus that adding market-rate homes to a market puts downward pressure on the price of other market-rate homes within that market. In the huge and often cruel game of musical chairs that is our housing market, the most important way to keep people from being locked out is to bring in more chairs. Almost nobody who studies housing policy disputes this much; the disagreements are all about which specific locations are affected in which ways and how much different groups of people benefit.

On which note, there is a separate, legitimate question about whether newly built infill homes can themselves ever be cheaper than the old homes they potentially replace. The answer is: sometimes. One of the reasons Portland legalized fourplexes (rather than triplexes, like in Minneapolis or Vancouver before it) is that splitting the land cost four ways saves money and (assuming you also have caps on building size) brings newly built market-rate homes into the price range of middle-income households. If you want to measure price per square foot, the new homes will almost never be cheaper than the old ones … but you also have to account for the fact that they’re new. Some people may prefer the design of old homes, but generally speaking new or recently remodeled homes are worth more because they are more pleasant to live in. Banning all housing investment would be one way to bring down home prices, but I don’t think it’d be very popular.

In any case, our real choice isn’t between “what is the price per square foot of this oneplex now” and “what is the price per square foot of the fourplex that might someday replace it.” We are actually choosing, with our zoning laws, between the oneplex that may one day replace the existing house (either a scrape-and-rebuild McMansion or a remodel) and the fourplex that may one day replace the existing house. Personally, I think it’s fine when cities have some of each of those things … but if we ban the fourplexes in a city with a growing economy, the only thing we get in the long run is a bunch of luxury oneplexes. I don’t think that’s healthy. We need a constant cycle of infill of different types to ensure many options for many different people in all locations.

Above and beyond all that, Portland’s mixed-income sixplex option is pretty straightforward: it’s only allowed if the builders agree to price restrictions on at least half the units. We expect it to be used mostly by nonprofit housing providers, because it doesn’t deliver enough return to compete with the stock market as a way for people to invest money. But maybe somebody will figure out a way to make it work, in which case newly built below-market homes will become MUCH easier to create. So much the better if that happens.

2) On environmental impact, the simplest reason plexes are good for the planet is that when you look at the full life cycle of a home, even in the temperate PNW, heating and cooling it for many years is a much larger use of energy than building it (including the lost embedded carbon emissions of a structure that gets demolished). And smaller, attached, newer homes are way way way more efficient to heat and cool than larger, detached, older homes — so much so that they pay for themselves in carbon savings after their first couple decades of existence. There’s also the fact that proximity reduces the amount of energy required for transportation, but that’s harder to quantify.

None of that is to say that we should be actively trying to get rid of well-functioning older structures. But as structures near the end of their useful lives, we aren’t helping the planet by banning plexes in hopes of squeezing another few years out of them. (After all, they might well be replaced by a big oneplex even if we ban duplexes etc.) Our environmentalist energy is better expended on popularizing deconstruction (as opposed to demolition), in my opinion.

Rik

“What is the rationale for calling these new units affordable if they are really market rate?”

“Affordable” can mean “subsidized,” or it can mean “something that people who are not wealthy can afford.” It means affordable in the latter sense.

Under normal conditions, it wouldn’t occur to people that “market rate” and “affordable” were antonyms. Only under circumstances of extraordinary hypergentrification (particularly in a small number of cities) would it be seen that way.

Michael Andersen

Well, in the case of the Portland and Austin sixplexes, we are actually talking about deed-restricted affordability requirements. Here’s an article I wrote that predated the final Portland plan, which after further analysis allowed up to half the homes to be market-rate as long as the other half were below-market.

https://www.sightline.org/2020/01/10/do-portlands-low-density-zones-need-a-deeper-affordability-option/

Cindy

No matter what the bill intends, the market will always prevail. If the builder can sell for “market rate” the sixplex or any other configuration allowed or not, and effectively leave an affordable buyer out in the cold, he will.

Great intentions. Unintended consequences.