The movement to prioritize housing for people over storage for cars has reached a new high point in the Pacific Northwest.

In the first action of this kind by any US state, Oregon’s state land use board voted unanimously last week to sharply downsize dozens of local parking mandates on duplexes, triplexes, fourplexes, townhomes, and cottages.

Many cities have reduced or eliminated parking mandates in recent years, including Oregon’s largest city, Portland.

But Oregon’s rule, which stems from its landmark 2019 legalization of so-called “middle housing” options statewide, is a much more unusual state-level action, affecting 58 jurisdictions simultaneously. And because middle housing will soon be legal throughout those 58 jurisdictions—the vast majority of the state’s urban lots—it’s arguably the biggest state-level parking reform law in US history.

Oregon’s new rules hold mandatory parking ratios at or below one parking space per home

Under the new state rules for larger cities and the Portland metro area, middle-housing projects on residential lots of 3,000 square feet or less can’t be required to have more than one off-street parking space, total, for the first four attached homes. For lots of up to 5,000 square feet, no more than two parking spaces can be required, total; for lots of up to 7,000 square feet, no more than three spaces. On lots larger than 7,000 square feet, a limit of one mandatory parking space per home applies.

In all cases, property owners will have the option to include as many off-street parking spaces as they feel the project needs. Their projects simply can’t be required to have more than one space per home, even on the largest urban lots.

This new standard applies to areas that are home to 2.5 million Oregonians, or 60 percent of the state’s population.

Last week’s vote by the governor-appointed Land Conservation and Development Commission will strike down the current parking mandates in Salem (1.5 per home), Eugene (1 per home), Gresham (2 per home), Hillsboro (1 per home), Beaverton (as many as 1.75 per home), Bend (as many as 2 per home), Medford (1.5 per home), Springfield (as many as 2 per home), and many other cities.

In 22 smaller Oregon cities, those between 10,000 and 25,000 population, duplexes will be legalized on all lots. As part of that, duplexes in those cities will no longer be required to have more than one space per home. Another eight percent of Oregonians live in those cities.

“I think it’s great for Oregonians,” said Sara Wright, transportation program director for the Oregon Environmental Council. “We have limited public and private space; we have increasing population. It’s great to give us more flexibility in the way we build our communities.”

“We can now use that space for more housing, more space for others,” said Timothy Morris of the Springfield Eugene Tenant Association, who sat on a state advisory committee that helped vet the rules. “We can even add entire units of housing where parking spaces would have been.”

Wright and Morris were among a coalition of environmental and housing advocates and professionals from around the state, organized by Sightline, who had urged the state commission to pass such a policy.

Mary Kyle McCurdy, deputy director of the anti-sprawl group 1000 Friends of Oregon and one of the architects of Oregon’s middle housing legislation, sat on both advisory committees and watchdogged the commission process over the last year. She credited various factors, including direct input from middle-housing developers and good research by state staff, for building consensus around the change.

“I think it disproved the notion that some of these parking changes were coming from a Portland perspective,” McCurdy said. “That was not at all the case.”

People should not be required to pay for parking spaces they don’t need

The new rule was approved as part of the Oregon Land Conservation and Development Commission’s deliberation on how to interpret a crucial two-word phrase in the state’s landmark 2019 law that legalized middle housing statewide.

The phrase: “Unreasonable costs.” Under the law, cities are not allowed to subject middle housing to unreasonable cost.

That phrase in the law required the state to define, alongside a “middle housing model code” that cities now have the option of adopting, a “minimum compliance standard” with which all cities will be required to comply or be declared “unreasonable.”

(Among the many other pro-housing aspects of the minimum compliance standard that’ll be applied to larger cities and the Portland metro area: For townhouse projects, a minimum average lot size of no more than 1,500 square feet. Writing in CityLab in July, Emily Hamilton of Mercatus Center persuasively identified two crucial ingredients of effective middle-housing legalization: low parking requirements and small minimum lot sizes.)

To arrive at the new parking standard, state staffers commissioned a study to examine possible costs and lot layouts for new duplexes, triplexes, and fourplexes. It concluded that for such structures “on small lots, even requiring more than one parking space per development creates feasibility issues.”

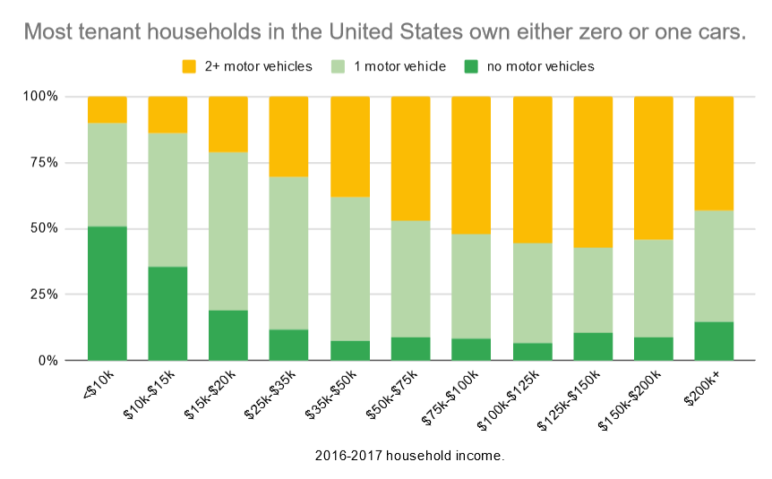

Separately, drawing on prior research by Sightline, state staffers looked at car ownership rates around Oregon. They found that in every affected city, at least 40 percent of tenant households own one or zero cars.

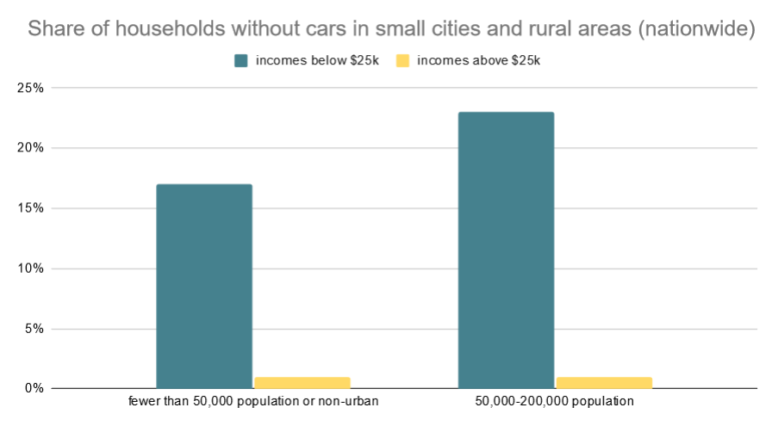

Even in smaller cities and rural areas of the United States, living without a car isn’t all that unusual. It’s simply concentrated among poorer people:

In other words, building lots of off-street parking adds costs that can block projects. And many Oregon households, even in fairly small and rural cities, have little use for it.

Therefore, the staff concluded, it’s unreasonable for a city to require parking spaces whether or not a home’s resident is likely to want them. The reasonable approach is to make it a site-specific decision by the landowner.

The state commission agreed.

A lesson for advocates: Reform parking within the context of things people want, like housing

Fifteen years after Sightline was among the first outlets to call attention to an odd new book by UCLA Professor Donald Shoup, The High Cost of Free Parking, there is now widespread belief among both housing advocates and environmentalists that citywide parking mandates are a bad idea.

“One-size-fits-all rules—they don’t take into account a lot of context,” said Tony Jordan, the Portland-based founder of the Parking Reform Network, a national advocacy coalition launched last year that has Shoup, among others, on its advisory board. “They don’t take into account the fact that there are a lot of households that don’t have cars. They don’t take into account that there’s a lot of existing supply [of parking space] on the streets.”

If you want to mandate off-street parking, Jordan said, “you’re going to have to cut down trees and you’re going to have to pave more surfaces.”

It’s much better, Jordan and others are arguing, to let property owners make site-specific decisions about their parking needs.

But parking reformers face a political challenge. How to eliminate parking mandates without triggering a “war on cars” freakout?

Oregon’s latest win, along with recent reforms in Washington, California, Minneapolis, and Portland, offer one possible answer: Embed the parking reform inside other reforms.

By embedding their parking reforms in efforts to create more and cheaper homes, these states and cities focused attention not on what their residents stand to lose (abundant parking space) but instead on what residents stand to gain (abundant and cheaper homes).

Morris, the Eugene-Springfield tenant advocate, said that’s the way he thinks about the issue.

“Our health, our planet, our future—the benefits are really grand and the negatives are slightly less parking,” he said. “So I’ll take the pros with the con any day.”