For US housing advocates both inside and outside Washington DC, the last six months are looking a lot like a big waste of time. For millions of people in dire need of renter aid, it’s been very personal evidence of government dysfunction.

Congress spent six months working out a way to structure a second package of emergency aid for the millions of Americans facing an abrupt housing crisis. Then, after a bipartisan agreement seemed to be coming together, it was sabotaged by a presidential tweet before being finished off on Monday night when Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell adjourned the Senate.

Meanwhile, about 10 percent of all renters tell US Census surveyors they have “no confidence” in their ability to make next month’s rent—and most of those people are probably right.

This isn’t the way things have to go.

Senate staffers shouldn’t have to craft vast new rental subsidy systems in a rush while the clock ticks toward potential evictions for a million US households. The safety net families rely on to catch them during an emergency, like a global pandemic, shouldn’t hang by a thread on the political calculations of top lawmakers. And you definitely shouldn’t have to follow the president on Twitter to figure out if you’re losing your home.

There’s a simple alternative, and it’s something the incoming 117th Congress could do on behalf of generations of future Americans hit by disasters. People could automatically receive housing subsidies whenever their incomes go down.

This isn’t a novel idea. It’s how things work all the time in Germany, Australia, the United Kingdom, Japan, Denmark, and elsewhere. As the coronavirus has swept around the globe this year, shutting down much of the world’s entertainment and hospitality industries, other nations’ existing housing subsidies—generally cash payments to people who meet income and residency qualifications—have kicked automatically into action. When unemployment insurance doesn’t flow or runs out, low-income housing subsidies are a last line of defense, helping keep people’s lives from collapsing like dominoes.

But things work differently in the United States.

Ending Section 8 waitlists would avoid debacles like this fall’s

Renter aid should kick in automatically. “Eviction,” photo by wolfpeterson, used with permission.

The main US rental subsidy program is called Housing Choice Vouchers or (more often) “Section 8,” because it’s funded by that passage of the Housing Act of 1937.

Compared to rental subsidies in other rich countries, Section 8 is unusual in two ways.

First, it cuts tenants out of the money, instead sending cash directly to landlords and relying on local housing authorities to decide when landlords aren’t adequately meeting tenants’ needs.

Second, a person losing their income must generally wait years before even hoping to get voucher benefits. Seattle’s Housing Choice Voucher waitlist has been closed since 2017; Portland’s, since 2016. When waitlists do occasionally open, you have a window of several days to enter your name in a high-stakes lottery. If you get lucky, you get to keep the voucher indefinitely—unless your income goes up, in which case you risk going to the back of the queue if you ever need help again. (Another way to blow your lucky lottery draw: move. If you can’t find a home in your price range that accepts vouchers within 60 days, your voucher can expire.)

The current Section 8 system, in short, makes it riskier to get a job or to relocate for work, training or family—precisely because it isn’t fully funded.

Other safety-net programs don’t work like this. SNAP—food stamps—doesn’t threaten to yank your benefits if you switch grocery stores. If you’re getting an unemployment check, taking a job won’t blow your chance to ever get another. Congress doesn’t have a fight every month about how many poor kids’ lunches it’s willing to pay for.

Making Section 8 work more like SNAP would offer a double benefit. During normal times, these programs send help to those who need it, before misfortune can metastasize into long-term poverty. And during national catastrophes, it helps pull the entire economy out of a tailspin by pushing out cash quickly—no special Senate session required.

Ending Section 8 waitlists would automatically soften recessions

My favorite Internet meme of 2020 came and went very quickly last spring—a flash in the pandemic.

Image via KnowYourMeme.com.

For a week or two in March, this character (I guess he’s called Wojak) was popping up all over, urging the federal government to stave off a depression.

Accompanying it was a boomlet of talk about “automatic stabilizers“—recession-fighting checks that would mail themselves the moment economic indicators point to recession.

This is probably a good idea. Whenever the next economic disaster hits, Americans won’t want their representatives to once again act like two lifeguards fighting over who gets to throw the life preserver.

But there are also other ways to get at this. Any government benefit that goes automatically to low-income people is an automatic stabilizer, because one of the main things about recessions is that a bunch of people’s incomes go down. SNAP, writes the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, is “one of the fastest, most effective forms of economic stimulus.” According to a US Department of Agriculture study, each dollar of SNAP spending during a downturn boosts GDP by $1.50.

Fully funding Section 8 would work this way, too. But it could only be done at the federal level, not the state level. Only Congress and the Federal Reserve have the power to just create more money. Because states can’t issue their own currencies, a state government that tried to spend its way out of a recession would go broke.

As much as we Sightliners hate to say it, durable rental subsidies can’t come from Cascadia alone. They’ve got to be federal.

Ending Section 8 waitlists would sharply reduce poverty

Ending Section 8 waitlists by fully funding the program would reduce the US child poverty rate by about one-third, from 13.6 percent to 9 percent, pulling 3.4 million US children out of poverty. Photo by Phillipe Put, used with permission.

The last reason that the next Congress should turn its attention to fully funding Section 8 might be the most obvious: It would make a lot of people less poor. Especially young people.

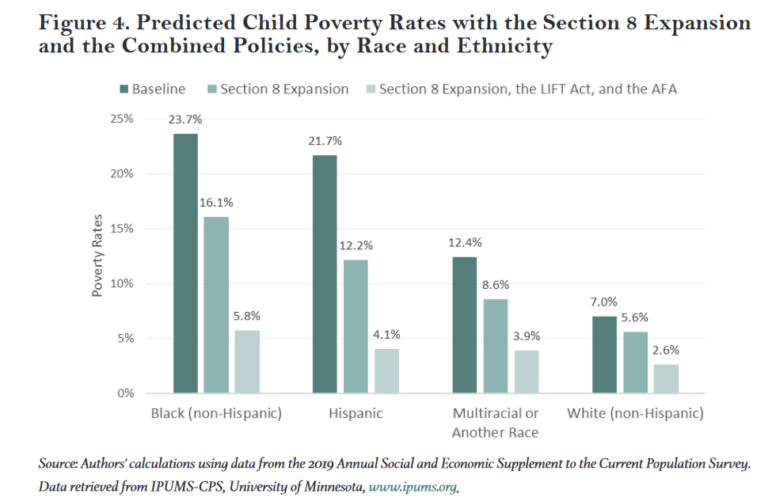

Earlier this month, a team of Columbia University researchers calculated that offering Section 8 vouchers to every American who qualifies for them would slash U.S. poverty rates by a quarter and child poverty rates by a third.

None of the other antipoverty policies considered by the study would do more.

Looking at race and ethnicity, US children of Hispanic descent would see a particularly large benefit, moving from a 22 percent poverty rate down to to 12 percent from vouchers, or just 4 percent with other policies in combination.

This paper doesn’t attempt to estimate the secondary effects of an expansion like this; it’s likely that without the hassle of waitlists, some people would work less, which could offset some benefits of the program. But the authors do cite a National Academies of Science report that estimated the poverty-reducing effects of a Section 8 expansion would be 16 times larger than the poverty-boosting effects.

What’s more, eviction and homelessness are expensive for society in part because they’re bad for your health, and targeted rental subsidies (whether to landlord or tenant) seem to be extremely effective at reducing homelessness.

And then there’s the fact that without Section 8 waitlists, people wouldn’t have to fear that accepting a job opportunity or moving to a new place might cost them their vouchers forever. The average SNAP user is off benefits in about nine months. The average voucher recipient, who knows how hard it would be to ever regain a subsidy, remains for more than six years.

Like every public program, Section 8 is imperfect. In future posts, I’ll explore one big way we could improve it: By sending the cash to tenants instead of landlords.

But even imperfect, the numbers suggest it’s a system worth investing in.

Jim Wavada

Amen, Mr. Anderson.

For my sister, who qualified for a Section 8 housing voucher last summer, but ended up letting it expire, it wasn’t just an issue of availability. It was about gross inadequacy. The amount our Section 8 administrators would allow her to spend on rent in our region is about $600 less than the average monthly rent here in Spokane.

There’s a very low percentage rate of redemption on these vouchers in our region as a result of that inadequacy, not just the wait in line. Section 8 housing shoppers can’t find anything in their price range.

I offered to help my sister by supplementing her Section 8 voucher with a cash contribution. But again, HUD doesn’t allow that. You lose your voucher if you pay more for lodging than the voucher authorizes. There are small, insignificant adjustments to the maximum monthly, but they are hard to get and generally based on special needs like handicap access.

So maybe a good first step would be to start matching the voucher amounts to the current local market process and not some number an analyst in Washington, D.C. came up with based on the size of an appropriation amount from a decade ago.

Michael Andersen

That’s a wrenching story about your sister, Jim. I’m glad to say that here in Portland, the local housing authority Home Forward allows people to make up the difference with cash out of their pocket. Not that that’s a great solution, but if low-income people are able to pay more than 30% of their income for the home that’s best for them, they should be able to IMO.

asdf2

Another elephant in the room regarding section 8 is that fully funding it it doesn’t actually do anything to address the pigeonhole principle.

If you have 500,000 pigeons trying to fit into 450,000 holes, no matter what you do, 50,000 of the pigeons won’t find holes. Under the free market system, the pigeons bid each other up on the holes until 50,000 of them are priced out, and you have equilibrium. Under a partially-funded section 8 system, a few of the pigeons who would have otherwise been priced out are given enough subsidy so that they can find a hole and somebody else (e.g. someone less lucky in the lottery) gets priced out instead. Either way, 50,000 pigeons are still priced out. And, if you try to fully fund it – pour however much money it takes into the system so that every pigeon who wants a hole is able to afford one – the government simply gets into a bidding war with itself and prices go to infinity. Because, at the end of the day, when there’s 500,000 piegons and only 450,000 holes, no matter how you slice and dice it, 50,000 of the pigeons must not get a hole.

Ultimately, the only way to break this is to break through the NIMBY’ism and increase the housing supply.