Fossil fuels will eventually phase out. An array of forces are moving against them, including the imperatives of decarbonization, rapid growth in clean energy, and global energy markets rocked by turmoil and contraction. All of these factors are good—maybe even vital—for the global climate, but they also pose challenges for oil-dependent regions, the people who extract and supply carbon energy to the rest of us. It’s one thing to advocate for a transition to clean energy and it’s another thing to advocate for a just transition that values the communities most at risk.

The hollowed-out coalfield communities of Appalachia are just one example of how crippling an unplanned transition from resource extraction can be. A similar fate could be in store for the places that feed the Northwest’s prodigious appetite for fossil fuels. Although many of these places are beyond the borders of Cascadia, they are importantly linked to the Northwest by decades of energy commerce. Foremost among them is Alaska, which has become an alarming cautionary tale about binding a state’s fortunes too tightly to a volatile energy commodity. Historically the biggest supplier of fuel to Cascadia, Alaska and its fiscal meltdown deserve attention from those advocating for a transition away from fossil fuels. So too should we look to North Dakota which, along with Alberta, supplies most of the rest of the Northwest’s oil.

The 2020 bust in oil markets is a dry run—a sort of practice round for a transition—that we should reference when making plans for a more permanent shift to clean energy. We also have an opportunity to examine how oil-dependent regions can manage a graceful transition to a carbon-free future. Such a change is feasible but will require intention and smart policy.

To understand what’s possible, and to give Northwest climate hawks a policy goal to aspire to, we can look to a success story abroad: Norway. A prodigious oil producer, the country has squirreled away petroleum revenues for more than 20 years, creating the world’s largest sovereign wealth fund. By doing so, Norway has positioned itself to move its economy beyond oil without compromising its social safety net, a practice that can serve as a model for North American oil regions.

A “sovereign wealth fund” is a government-owned investment fund functioning as a long-term reserve for public coffers. Often derived from the sale of energy or mineral commodities, one of the most well-known sovereign wealth funds in North America is Alaska’s Permanent Fund. Several other states have funds too, including Alabama, Louisiana, New Mexico, West Virginia, and Texas.

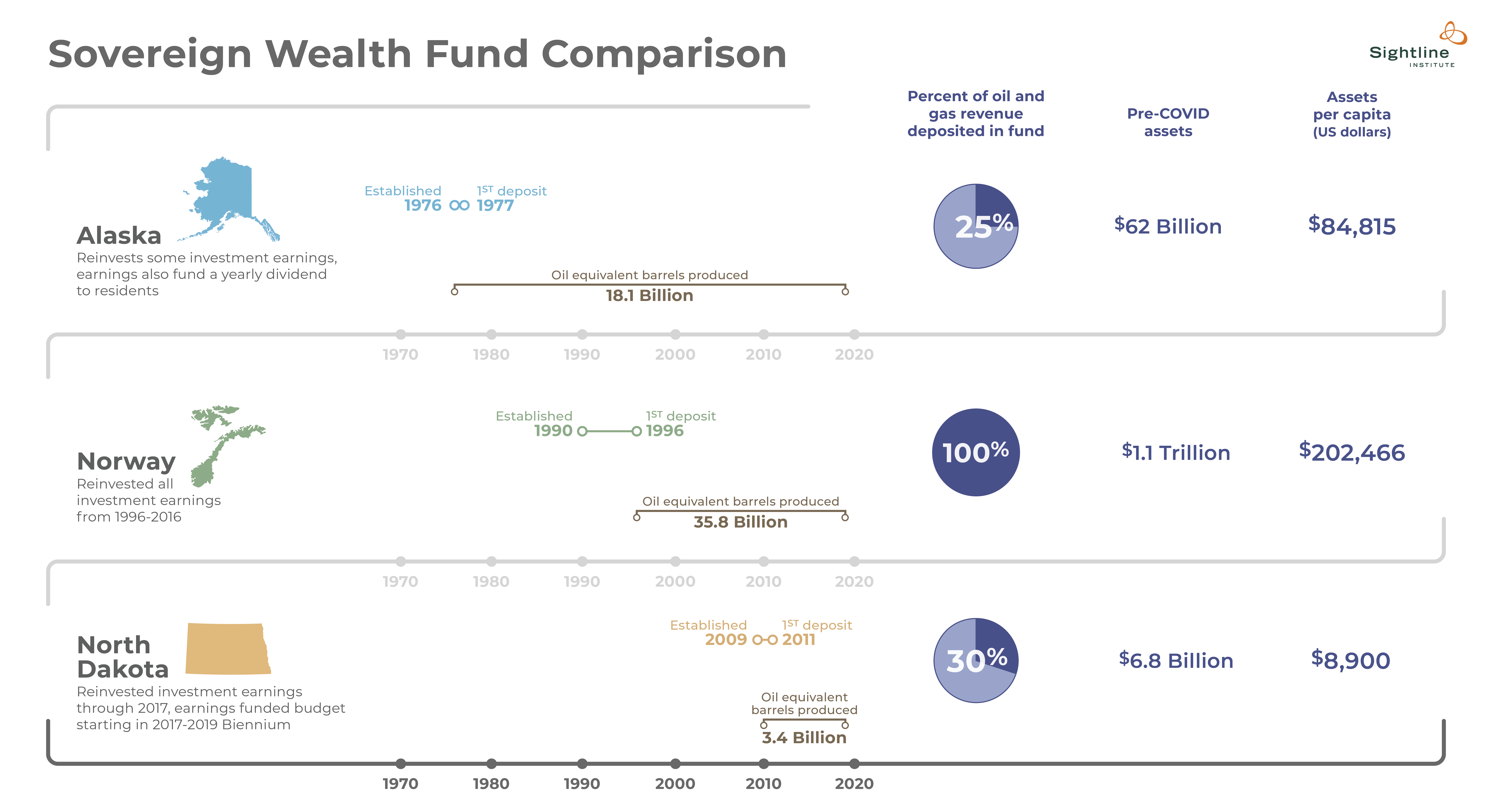

North Dakota, too, has a sovereign wealth fund, though it is just over a decade old. Created in 2009, it saw its first deposit (to the tune of $10 million) in September 2011 as fracking in the western rangelands that sit atop the Bakken shale formation began to pick up steam, and as the first trains loaded with light shale oil began arriving at Puget Sound refineries. As of May 2020, the North Dakota Legacy Fund could boast the tidy sum of $6.8 billion—big enough to give North Dakota policymakers some choices yet still small potatoes compared to Alaska’s $62 billion Permanent Fund and Norway’s $1 trillion wealth fund.

Those choices could come in handy now because North Dakota’s oil industry is in trouble. One of the centers of the “shale revolution,” the state’s drilling skyrocketed in the 2010s but then went bust this year. Lynn Helms, director of the North Dakota Department of Mineral Resources described the second quarter of 2020 as “a five-alarm fire for the North Dakota oil and gas industry.” By April, Continental Resources, the largest oil producer in North Dakota, had reportedly stopped all drilling and disabled most of its wells. In May, as prices slumped to around $25 per barrel, Hess Corp, a major oil producer in the state, found itself so glutted with un-sellable crude that it resorted to purchasing three super tankers to store what it could not sell. In fact, oil production in May 2020 was down a full 40 percent from a year before and there are indications that the industry will contract further, with some experts arguing that 70 percent of shale oil rigs in the state could be shut down by fall. As of August 14, only 11 drilling rigs were still running in the state, down from 52 in March.

Now, North Dakota sits at a crossroads.

The state could follow Alaska’s lead, giving money back to residents while refusing to raise revenue for government services even as oil money dries up, leaving the state in a serious fiscal jam. Or, it could simply spend away the assets, as Alberta did, where a once-valuable asset is now only worth a small fraction of what it was. (Economists at the University of Calgary estimate that Alberta’s Heritage Fund could have been worth nearly $500 billion if it had been managed similarly to Norway’s Sovereign Wealth Fund.)

What would it mean for North Dakota to manage oil wealth as Norway has? To mark out a better path for other oil-dependent regions, it’s worth understanding a little about the Norwegian success story.

To mark out a better path for other oil-dependent regions, it’s worth understanding a little about the Norwegian success story.

Although Norway’s Sovereign Wealth Fund is scarcely 30 years old, it is now the largest in the world. With total assets valued at over $1.1 trillion before the COVID downturn, the Fund owns a staggering 1.5 percent of all listed stocks globally. Norway is home to just a little over five million people, so the Fund’s value works out to about $200,000 per resident. By contrast, Alaska’s $62 billion Permanent Fund has assets worth just over $84,000 per resident and North Dakota’s Fund is worth around $9,000 per resident.

Alaska actually produced more oil than Norway on a per capita basis but retained far less wealth. The reason for the difference is mostly due to money management. Norway reinvested all of its net revenue from oil and gas taxes in its sovereign wealth fund while Alaska saved only a quarter of its oil revenues. In short, by reinvesting its dividends, Norway secured financial stability for the foreseeable future, regardless of what happens to the oil industry.

Full-Sized Graphic, Sovereign Wealth Fund Comparison (822 downloads )

Norway is, in fact, preparing for a shift to clean energy, projecting a decrease in oil production to just 25 percent of 2015 levels by 2060. As Norwegian oil production phases out mid-century and oil revenues disappear, the country will be able to systematically withdraw money from the Fund to support important government programs. The situation is very different in Alaska where the state legislature has slashed public budgets while raiding its oil funds. Of course, Norway’s ample sovereign wealth fund can also be tapped during a crisis. In response to the COVID-related economic downturn, for example, Norway withdrew $37 billion, 4.2 percent of the Fund’s total value, to cover budget shortfalls.

Norway is, in fact, preparing for a shift to clean energy, projecting a decrease in oil production to just 25 percent of 2015 levels by 2060.

What’s the lesson for North Dakota? The state’s Legacy Fund is much smaller, currently worth just $6.8 billion or about $8,900 per capita, but it can be grown into a durable safety net. In recent years, the state has been producing roughly the same amount of oil as Norway, but it sets aside only 30 percent of oil and gas tax revenue for the Fund’s principal. North Dakota hasn’t safeguarded the money either. Although the legislature is prohibited from spending more than 15 percent of the principal during any biennium, lawmakers have not been able to resist the temptation to raid the fund. In 2019, the legislature took more than $450 million to balance the state budget and shore up school funding. As North Dakota grapples with painful recession-induced budget shortfalls, it’s likely the legislature will take more. In an effort to preserve the Fund’s integrity, some legislators have proposed establishing a reserve fund within the Legacy Fund, which would be used to cover budget shortfalls without drawing down the principal. The idea has not yet come up for a vote.

Depleting the Fund is risky business because it is the main way that North Dakota can prepare itself for the inevitable transition away from oil.

Analysts at the Great Plains Institute, a Minnesota-based think tank, have studied wealth funds from around the world. According to their projections, if North Dakota were to spend all the earnings from the Fund (similar to Alaska), it would be worth around $77 billion by 2060, roughly the same as Alaska’s Permanent Fund on a per capita basis. If it were to reinvest all of its earnings (similar to Norway), North Dakota’s Legacy Fund could be worth as much as $450 billion, about $450,000 per person in the state. That amount is more than double the current per capita value of Norway’s Sovereign Wealth Fund, which would put North Dakota in an enviable position. The Fund could finance major government services in perpetuity and position the state for the inevitable transition away from fossil fuels without needing to cut government services. If managed well, the money could also cover the costs of job training, direct cash payments, and public budgets for things like roads and schools. (The Institute’s projections were made prior to the 2020 meltdown in oil markets, so they are likely too rosy, but still they give a rough sense of the possibilities.)

During a recession, a more politically palatable option may be some middle path between Alaska and Norway. One such route is in line with what Better Plains Institute argues for: not spending any of the principal amount until at least 2040, reinvesting 75 percent of the annual earnings, and spending the remaining 25 percent of earnings on long-term investments like education.

Change is coming—certainly to energy markets and perhaps to our political systems—which means that the right time for innovation is now. Northwesterners looking to build a climate-responsible future in the region should look not only to fossil fuel reduction plans, but also to careful strategies that support a managed and just transition for the oil-dependent regions and communities that could be left behind.

Zane Gustafson is a freelance researcher who holds a master of public affairs degree, with a focus in climate policy, from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington. He also studies foreign affairs, political rhetoric, and American history.