Unemployment insurance and other emergency COVID-19 supports have worked to date to help keep renters in their homes. But as benefits and eviction bans expire over coming days and weeks, time is running out for Congress to act with adequate relief to stave off disaster for renters across the US—and for the US economy.

Back in March when pandemic shutdowns triggered massive job loss throughout the US, the future looked dire for millions of unemployed tenants unable to pay the rent. Since then, the number of renters missing payments has risen, but while families are struggling across the nation, the widespread renter catastrophe feared by many has not materialized.

The main reason? Federal aid.

The CARES Act, passed in late March, enacted a $600 per week unemployment benefit to supplement state payments. Over 12 weeks, we estimate that has put an extra $42 billion into the pockets of unemployed renters. For perspective on the hefty scale of that support, America’s 44 million renter households pay a total of about $40 billion in rent per month.

But the $600 benefit expires July 31, and unless Congress extends it or approves another form of aid to compensate, the grim predictions for unpaid rent and evictions will finally start to play out for millions of renters across Cascadia and the US.

African Americans face disproportionate risk, being more likely to rent, and more likely to spend a bigger share of their income on rent. As of early July, 29 percent of surveyed US Black renters said they didn’t pay June rent, compared with just 13 percent of white renters.

In May, House Democrats passed the HEROES Act that would maintain the emergency unemployment payments through the end of the year, and also provide $100 billion to support renters. But Senate Republicans rejected the House bill and are developing their own relief package—likely rolled out this week.

Senate leadership has indicated that their bill will extend unemployment benefits, though probably with a sharply reduced payment amount. Additional aid targeted for renters appears unlikely at this point. But with the volatility of US politics these days, a change of course on rental assistance is not impossible.

Given the severity of the coronavirus crisis and economic fallout, the appropriate solution to rescue renters in this widespread American crisis would include both cash to cover rent specifically and unemployment payments to help out-of-work renters keep up with the rest of their bills and stay housed.

Congress can protect renters through a combination of rental assistance and an extension of supplemental unemployment benefits.

The window of opportunity is closing fast. Congress traditionally takes an August recess and after that, the looming November election will consume everyone’s focus, leaving slim chances for another major coronavirus aid package this year unless both houses of Congress can agree on something before the end of July.

What’s been helping renters stay in their homes?

Aside from the $600 per week federal unemployment insurance (UI) benefit, a patchwork of state and city eviction bans has been a key factor keeping renters in their homes. Most major cities and many states banned evictions early in the pandemic, though many of these emergency measures have now expired or will soon. The CARES Act halted evictions in rental buildings funded by federally backed loans, but that protection ends July 31.

But eviction bans are a temporary fix. The rent people owe accrues and comes due when the bans end. Most renters who have been out of work won’t have the resources to pay back several months of missed rent right away.

To soften that blow, Washington, Oregon and a few local governments including Seattle, Portland, Beaverton, and Multnomah County will require landlords to offer tenants extended payment plans to pay off back rent.

The CARES Act also provided $12 billion for HUD programs, to be distributed by state and local governments that can choose to use the funds for rental assistance.This scale of renter support comes nowhere close to the need, however.

For example, Washington put $100 million of its CARES Act funding toward rental assistance, but that won’t go very far in a state with one million renter households. If one fifth of them qualifies for aid, that comes out to a one-time payment of just $500 per household. At a similar ratio, Alaska allocated $10 million and has roughly 90,000 renter households.

Some cities and counties have established or bolstered rental assistance programs, but invariably, here again the need dwarfs available funding. For example, in April Seattle partnered with the United Way of King County to offer $5 million in renter aid to support 2,000 families—equivalent to a one time payment of $2,500 each. But King County has 370,000 renter households, 22 percent of which were already “severely cost burdened,” spending half or more of their income on rent.

The single biggest chunk of aid in the CARES Act is the $653 billion Paycheck Protection Program (PPP), which grants businesses loans that are forgivable if they retain employees and wages. As of June 30, the PPP had approved a whopping $521 billion in loans. At the start, processing snags delayed loan payouts, but a recent Census survey found that 75 percent of US businesses applied and 72 percent received funding.

PPP preserves renters’ housing security by preserving their paychecks. It’s difficult to quantify, but the reach and magnitude suggests it’s likely keeping millions of renters solvent. The PPP is also a major economic stimulus: it’s full budget is equivalent to 3 percent of the $21 trillion 2019 US gross domestic product. But, the program has already awarded four fifths of its funds, and when the rest is gone that’s it, unless Congress votes to appropriate more.

Will Congress rescue renters with a generous enough spending package? Photo: Dan Bertolet, used with permission.

How much federal unemployment aid is reaching renters?

Across the US, the state average UI payment is $378 per week. The benefit amount varies according to the previous income lost. Currently, it ranges from $188 to $790 per week in Washington, $151 to $648 in Oregon, $72 to $448 in Idaho, and $56 to $370 in Alaska.

Part-time and minimum wage workers—whose jobs have been disproportionately impacted by the COVID-19 shutdowns—receive payments on the low end of the scale. The minimum Washington state unemployment check would cover only about half of the $1,674 average monthly rent in King County, the Northwest’s most expensive housing market.

The CARES Act’s $600 per week federal supplement is a big increase over state benefits, especially for low-wage workers. Also, in states such as Idaho and Alaska where benefits are on the low side relative to the national average, the federal boost is proportionally larger.

As noted above, the federal UI benefit has been delivering an unprecedentedly enormous amount of aid. Based on the US total number of active claims each week between March 29 and June 20, the outlay has been averaging $53 billion per month, for a total of $147 billion.

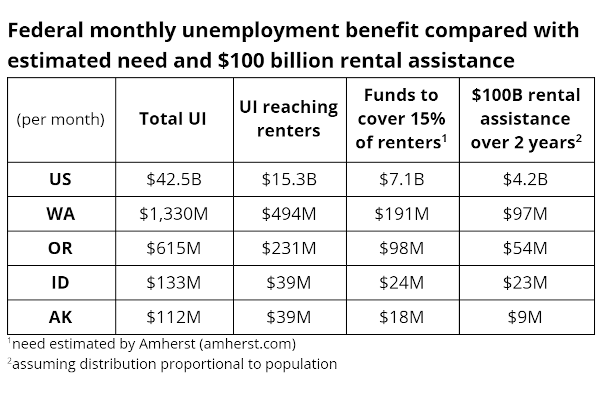

However, we estimate processing delays have held back 20 percent of those payments (based on reconciling treasury data reported by Bloomberg with claim counts tracked by the Opportunity Insights Economic Tracker). The table below shows the estimated UI dollars that have been actually reaching recipients in the US and each Pacific Northwest state, after applying the 20 percent reduction factor (analysis by the Century Foundation yielded similar results).

Compared with homeowners, renters are more likely to work the kinds of jobs that have disappeared in the shutdowns. But for the data shown in the table below, we conservatively assume that the UI benefits are split according to the ratio of owner versus rental households. Based on our assumptions, US renters have been receiving $15 billion per month, on average.

For renters in Washington state, it adds up to $1.3 billion received during the 12 weeks from late-March to mid-June. That’s 13 times the above-noted $100 million of CARES Act funding the state allocated to rental assistance.

How much assistance do renters need?

How much would it cost to cover rent for all the people who’ve lost earnings due to the coronavirus? Several organizations have published estimates (see table above for state-level data):

- Terner Center (UC Berkeley): $19.5 billion per month as an upper limit worst case scenario: the rent paid by 16.5 million renter households that have a member with a job in an “immediately impacted industry.”

- Urban Institute: $16 billion per month to cover two in five (17.6 million) renter households; $5.5 billion per month to return 8.9 million impacted renter households to their previous rent-to-income ratio.

- National Low Income Housing Coalition: Initially $9.9 billion per month to cover 12.7 million renters, and scaling down to $7.1 billion per month by June 2021.

- Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies: $7.5 billion per month for 9.3 million renter households with “at risk wages.”

- Amherst (research consultants): $7 – 12 billion per month for an estimated 15 – 26 percent of US renter households expected to need assistance based on their employment industry.

- Zillow: $2.9 billion per month based on actual unemployment claims in April combined with census data on rent payments by industry.

Excluding the two highest estimates, which are worst case scenarios, the average is around $6 billion per month. In comparison, as shown in the UI table above, we estimate total UI payments to renters of $15 billion per month.

While our analysis indicates that the UI benefits greatly exceed the likely rental assistance need, it’s important to remember that UI is intended to cover all living expenses, not just housing, which is typically around a third of total household expenses.

One drawback of relying on UI to support renters is that it won’t reach all renters in need. Rules vary, but some part-time workers or those with patchy work history, for example, may not be eligible. Undocumented workers in particular likely face formidable barriers to accessing UI. On the other hand, some renter households receiving UI may not actually need to put it toward rent—for example if another member of the household is highly paid and still employed.

Both scenarios underscore the advantage of a renter aid program based on a demonstrated lack of capacity to pay rent, not on employment status. Properly means tested rental assistance can target aid to all those, and only those, who really need it to avoid losing their homes.

Will CONGRESS rescue renters?

The HEROES Act, passed by the House in May, includes $100 billion for emergency rental assistance. The funds would flow to local governments through the federal Emergency Solutions Grant program, which would determine renter eligibility based on need. In late June, the House also passed a stand alone $100 billion rental assistance bill, but the Senate’s companion bill was all but dead on arrival.

If the $100 billion was spread over two years, the payout to renters would average $4.2 billion per month, a level of support that falls in the lower range of the need estimates discussed above. It’s enough to cover a large share of those who otherwise couldn’t pay the rent because of the pandemic. However, unemployed renters receiving rent aid still may be unable to pay the rest of their household expenses. Rental assistance would lower, but nowhere near eliminate, the ongoing need for UI as the economic crisis drags on.

The fate of federal renter assistance now depends on whether the Republican-controlled Senate will agree to include it in the next coronavirus aid package, and initial reports indicate they won’t. Meanwhile, prospects look good for an extension of unemployment benefits, though likely with the payment amount reduced to somewhere between $200 and $400 per week. It’s still something, but such a severe cutback will put more renters at risk of losing their homes.

A stable home is fundamental for a good life, and the COVID-19 pandemic’s ongoing and catastrophic economic fallout threatens to deny that from millions of renters. Congress can protect renters through a combination of rental assistance and an extension of supplemental unemployment benefits.

Longer term, Congress can better prepare for the next crisis by making Section 8 housing vouchers an entitlement, or by establishing a new program to provide direct cash payments to households in need, but that’s another story.