Editor’s note, 12/30/2020: Readers may have noticed that John has been updating this material, in anticipation of one day reporting that the US has cancelled Chlorpyrifos (see his notes in the comments section). In the meantime, both the European Union and Health Canada, each of which unlike the US comes closer to implementing a “precautionary principle,” have banned nearly all uses of Chlorpyrifos. At the same time, the European Union also banned the chemical cousin Chlorpyrifos-methyl, used much less often in the US. The US Administrative Procedures Act establishes a deliberative process that means it will take time to reverse Trump’s actions to weaken pesticide protections; and then industry may sue. But the US Congress can take action now. Farmworker Justice, one of the organizations that Earthjustice represents against EPA on Chlorpyrifos, is petitioning Congress and the US Environmental Protection Agency. Concerned readers have the opportunity to sign on to the Farmworker Justice petition.

In early February, Corteva Agriscience, the largest manufacturer of the neurotoxic pesticide Chlorpyrifos, announced it would discontinue production of the chemical. It was probably no coincidence that the statement came the same day California banned in-state sales of the chemical. California’s decision was, in part, the result of more than a decade of pressure from farmworker and environmental organizations for the state to make up for federal government inaction.

Nearly 40 years ago, toxicology studies showed that Chlorpyrifos exposure can interfere with brain development, particularly in infants and children. Since then, evidence of the pesticide’s harmful effects on human health has steadily accumulated. Exposure is linked with neurological and respiratory complications in children, reduced fertility, and Parkinson’s disease.

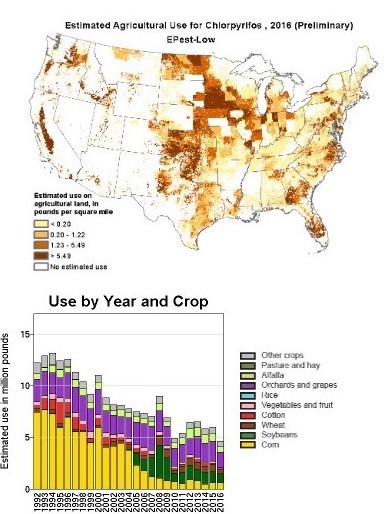

These findings are especially troubling given that Chlorpyrifos is widely used to control food crop pests. Cascadia’s farmers commonly spray it on regional staples including apples, pears, cherries, Christmas trees, lentils, and wheat.

Cascadia’s farmers commonly spray Chlorpyrifos on regional staples including apples, pears, cherries, Christmas trees, lentils, and wheat.

Foresters also apply Chlorpyrifos to control bark beetles or other boring insects.

So far, no Cascadian government has banned the pesticide. Oregon and Washington lawmakers have each considered legislation to reduce exposure risks, but neither state has taken decisive action. In both 2019 and 2020, Oregon lawmakers considered bills to ban Chlorpyrifos within the state, but in each chaotic session the legislature adjourned before voting on the proposals. Washington’s legislature passed a bill this year requiring the state’s Department of Agriculture to further regulate application of the pesticide, but Governor Inslee vetoed the bill due to budget concerns related to the Covid-19 pandemic.

British Columbia has also failed to act, though the chemical is already much less common in the province than in Pacific Northwest states. In 2015, BC residents bought fewer than 5,000 pounds of Chlorpyrifos, equivalent to less than four percent the amount sprayed on Washington apples that year alone.

Despite the lack of Cascadian action, California’s leadership on Chlorpyrifos may improve the safety of the food system in the Pacific Northwest and beyond.

Four decades of federal inaction despite mounting evidence of harm

In 1965, the United States approved application of Chrlorpyrifos in agriculture and for residential use. Within two decades, studies began rolling in linking exposure to the pesticide with adverse health outcomes, including delayed motor function and brain development in children. Though Congress tightened national pesticide regulations in the mid-1990s, high rates of childhood exposure to the potent neurotoxin continued.

Finally, in 2000, responding to mounting evidence of harm, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) negotiated a voluntary agreement with Chlorpyrifos manufacturers to end application in locations where children are mostly likely to be directly exposed—homes, schools, and daycare centers. But food crop application continued.

Unsatisfied with the voluntary agreement, the Natural Resource Defense Council and Pesticide Action Network continued to urge the federal government to ban the chemical outright. The request fell on deaf ears until five years ago, when EPA staff at last recommended ending Chlorpyrifos application on food crops. A year later, in 2016, the EPA reiterated the guidance, adding that food exposures to all age groups exceed safe levels. Children under the age of three face exposure 140 times “acceptable” levels. Farmworker families and their neighbors also bear high risk of acute exposure.

Despite the staff’s strong recommendation, president Donald Trump’s first EPA administrator, Scott Pruitt, refused to ban the chemical in 2017, and the US federal government has not taken action since.

Health Canada recommended a near total ban on Chlorpyrifos across Canada last year. As of this writing, the Canadian federal government has yet to act.

States step in

In the absence of federal action to ban Chlorpyrifos, state governments are stepping up. Attorneys general in multiple US states, including Oregon and Washington, have filed an administrative challenge against the EPA, calling on the Agency to cancel agricultural uses of the neurotoxin.

State legislators around the US are also taking action within their borders. In January, 2019, Hawaii became the first state to ban Chlorpyrifos application within its borders. California followed suit last fall, announcing that it would ban in-state sales of the pesticide by February 2020. In December 2019, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo also announced a state-wide ban, set to take effect July, 2021.

California is the largest US state by both population and agricultural sales, giving its pesticide regulations exceptional influence on the industry. Unsurprisingly, Corteva’s February announcement that it will terminate its Chlorpyrifos production followed on the heels of the Golden State’s ban.

Looking ahead

As the largest manufacturer of Chlorpyrifos, Corteva’s decision could radically slash use of the chemical across North America. Still, at least four other companies manufacture the pesticide: Cheminova, Makteshim-Agan, Gharda and Platte Chemical. None of these companies have yet announced plans to discontinue production.

California Governor Gavin Newson’s 2019 budget committed $5.7 million to look for alternative insecticides to replace Chlorpyrifos. Many of the options present risks of their own; for example, Imidacloprid and Clothianidin are neonicotinoids, a pesticide class linked with the decline in bee populations.

As the US federal government fails to act, and Canada’s lawmakers proceed with their review process, Cascadian governments could follow California’s lead and implement state- or province-wide bans. Though Oregon and Washington legislators failed to take decisive action on Chlorpyrifos in this year’s legislative sessions, they’ll have another chance next January.

John Abbotts is a former Sightline research consultant who occasionally contributes to Sightline articles. He recently served as in-house support contractor to EPA in Seattle, until he resigned in September 2019 in protest of the Trump administration’s efforts to damage the Agency’s mission to protect children and other living things.

A previous version of this article stated that the Washington legislature passed Senate Bill 6518 in its 2020 session, requiring additional in-state regulations on Chlorpyrifos application. While the bill did pass the legislature, Governor Inslee vetoed it due to budget concerns related to the Covid-19 pandemic. The article has been updated to reflect this.