Through five years of deliberation, Portland’s residential infill project has remained a simple concept: an anti-McMansion compromise that simultaneously lowers the maximum size of new buildings in low-density areas and allows buildings to contain more homes.

As the proposal finally arrives at Portland’s city council today for the first of two high-stakes public hearings, it’s also the most significant zoning reform project in the United States or Canada.

Over the years, the proposal has evolved, always for the better. Last year, it got a boost when Oregon ordered cities to legalize duplexes on any lot and fourplexes by right in every area. But Portland’s proposal goes well beyond that state mandate on abundance and affordability—which is why Portland’s anti-housing activists now find themselves arguing for the city to allow nothing on their blocks but the duplexes they previously loathed.

As the city council formally hears from its public, it’s worth reviewing the reasons this proposal would be so significant—in Portland and beyond.

1) Fourplexes are better than just triplexes because fourplexes let people save more money

In 2018, Minneapolis surprised the continent with the news that it would legalize triplexes on any low-density residential lot in the city. “Both simple and brilliant,” the editorial board of the New York Times wrote last June. “The most wonderful plan of the year,” said The Brookings Institution.

This is true, and future Americans will owe a debt of gratitude to Minneapolis for blazing a trail to low-density zoning reform in large cities.

But—no disrespect to my fellow Midwesterners—triplexes just aren’t as good as fourplexes.

It’s not just that a fourplex creates 33 percent more homes than a triplex. It’s not just that a fourplex splits the cost of land four ways instead of three. It’s not just that fourplexes give one more household the chance to join the team and, collectively, outbid one richer household for a particular piece of the city. In a growing city, legalizing fourplexes even reduces the number of demolitions it takes to add more homes—in the words of Portland housing advocate Holly Balcom, it makes every demolition count. (That’s the main reason Portland’s proposal is projected to reduce demolition-related displacement of low-income renters by 28 percent citywide—fewer demolitions would be required to create the number of new homes the city expects to need.)

The main reason fourplex homes would be cheaper than triplex homes is that, under Portland’s proposed rules, they would be smaller. That means they wouldn’t be right for every household—which is why triplexes, duplexes and oneplexes should remain legal. But Portland does not face a shortage of large homes, especially in close-in low-density areas. Just the opposite. Our aging population means more and more households are looking for small homes, especially on quieter streets. If only they’re allowed to exist.

You don’t need abstract theory to show that homes tend to be cheaper when they can share the land cost. You just need Redfin: listings like a sixplex home in Overlook selling for $298,500, a 12plex home in Vernon listing at $276,434, a backyard cottage in Sunnyside selling for $299,900.

All these options are far cheaper than any other newly-built home in their areas. This is not a coincidence. But, thanks to the oneplex-only zoning on three-quarters of Portland’s residential land, it’s not common, either.

2) Portland could pass a “deeper affordability” option that’d give a big leg up to nonprofit builders

Last spring, Austin took a different tack on reforming its low-density zones: it legalized sixplexes on every lot, without a cap on building size and a 40-foot height limit.

If you haven’t heard about this, it’s because the city imposed one key condition: To build up to six homes, at least half would need to be rented or sold well below market price.

This is why sixplex legalization hasn’t shaken up Texas’s high-priced capital city much, or made the national news. The only developers who’ve been able to consider these projects are nonprofits like Habitat for Humanity, which rely on limited external subsidies to close their funding gaps.

But although the homes created by this proposal are a drop in the bucket of the housing market, they’re a huge force multiplier for builders like Habitat, who use volunteers and private subsidies to extend homeownership to working-class families making less than half the median income.

Inspired by Austin’s example, housing advocates in Portland started running numbers—and realized that letting affordable-housing providers build up to eight homes on a lot, instead of just four, was the financial equivalent of cutting a check for $150,000 to every single home. But it wouldn’t cost the city a dime—all that’s required is to change the rules.

3) Building size would be regulated on a sliding scale

This one is wonky. But it’s the single most innovative concept in Portland’s zoning reform proposal. And it turns out to be hugely important.

Instead of simply setting a maximum size for all buildings in a zone, as Portland had originally proposed (and as other cities that have legalized plexes, like Vancouver BC and Minneapolis do), Portland’s current proposal takes advantage of something homeseekers (and therefore homebuilders) truly value: square footage.

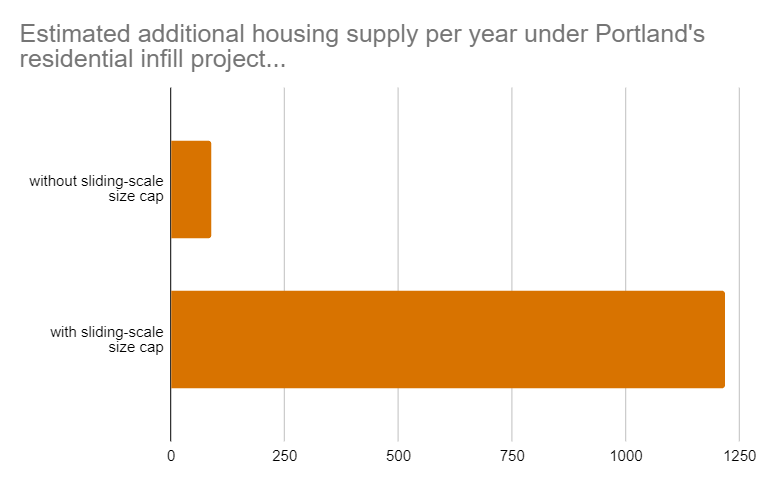

In 2018, Portland’s proposed reform used the same size ratio that’s in place in Minneapolis: the total square footage of a building could be half the size of the lot it sat on. (Technical term: a floor area ratio of 0.5.) This was projected to create just 87 net new homes per year.

Then, using the same methodology as before, the city ran the numbers on a different option (recommended by us, among others): let a building be a little bit larger if it creates either more homes or cheaper homes. It was a sliding scale of building size, designed to give developers a reason to act in the public interest rather than just their own.

Economists calculated that it’d work. The new proposal (which also included other tweaks) was projected to create homes 14 times faster. The reason: it turns out, when you look at actual sale prices, that a project’s value doesn’t depend much on the number of units in its structure. It depends on its size.

Giving developers something they want—a little bit more size—can give them a reason to do something you want, too. For example: creating more homes.

Until Portland, no other city was looking to rechannel private investment this way. Others are now considering it.

4) Garages would finally become optional

If you’ve been reading Sightline.org for very long, you probably know how we feel about mandatory parking rules: They’re hobgoblins that tear down trees, gobble up insane amounts of our civilization’s wealth, block the construction of the sorts of neighborhoods people seem to enjoy spending time in and act as a “fertility drug for cars.” Yet somehow, as the world’s climate clock ticks toward high noon, almost every city has them.

Driveways on low-density lots are particularly ridiculous because every driveway essentially eliminates a curbside parking space.

Garages and other off-street parking would remain a legal option under Portland’s residential infill proposal. But they would no longer be a requirement for residents who, for whatever reason, don’t feel the need for them.

It’s true that many Portlanders will continue to own cars and park them in the street. It’s true that in crowded areas, this can be annoying … but only to other Portlanders who want to do the exact same thing. And annoyance is no reason to prioritize parking a car over housing a family—which is exactly what a city does when it bans car-free homes.

5) The city could help ordinary homeowners use their new zoning

Last year, I pointed out that four is a magic number in disability law: Since 1988, any new building with at least four homes has been federally required to make the ground-floor units wheelchair-accessible.

Four also happens to be a magic number for something else: financing. It’s the largest number of homes for which the US government will back a traditional 30-year mortgage.

In practical terms, this means you don’t have to be friends with a millionaire to consider financing a fourplex on your property. You just have to open the door of a bank. And with a long-term loan, your initial cost basis is likely to be lower than a professional developer’s—which can let you compete with big developers on rent.

This democratization of development could be a good thing for small landlords and tenants alike. But it’ll only happen to the extent that ordinary Portlanders can actually navigate the financing system. The city has been trying for years to nurture an industry of lenders and appraisers with the knowhow to create loan products for accessory dwelling units, and that work finally seems to be paying off as banks and credit unions begin to create new loan products.

The city could build on that work by following in the steps of La Más, a Los Angeles organization whose Backyard Homes Project is a best-in-class program for helping homeowners finance ADUs in exchange for renting them to low-income tenants for several years. A few Portland organizations are eagerly pursuing the subsidized-ADU concept here. The city could support them by planning to fund subsidized-ADU models that work and support housing more generally by putting some effort into helping homeowners navigate the financing process for market-rate additions to their property.

One step in a long road to better housing

For all its big ideas and thoughtful details, Portland’s residential infill project is far from serving as a finish line. Good housing policy requires good zoning, adequate funding, smart taxation and constant attention to fairness and justice.

But Portland’s reform proposal deserves wide attention for what it stands to become: The most progressive reform to low-density zoning in American history.

At least until the next city gets inspired.