As the Alliance of Californians for Community Empowerment wrote in a powerful report Thursday, Californians suffer from an unprecedented housing crisis.

California’s colossal housing shortage is made worse, ACCE said, by the fact that several hundred thousand units are empty and currently unavailable for sale or rental. In at least some cases, that’s probably because their owners plan to ride the wave of rising prices that the state’s long-term shortage will continue to induce. The report and ACCE’s accompanying campaign emphasize the horrifying fact that Los Angeles in particular has more “non-market vacant” units than there are Angelenos experiencing homelessness on any given night.

ACCE is pushing for new taxes on long-term vacant homes, partly inspired by the one in Vancouver, BC. If a city has a high number of mostly-vacant “investment” properties, it’s a reasonable proposal.

But there’s an even bigger injustice this report overlooked, as do most of the similar exercises about empty apartments that circulate now and then.

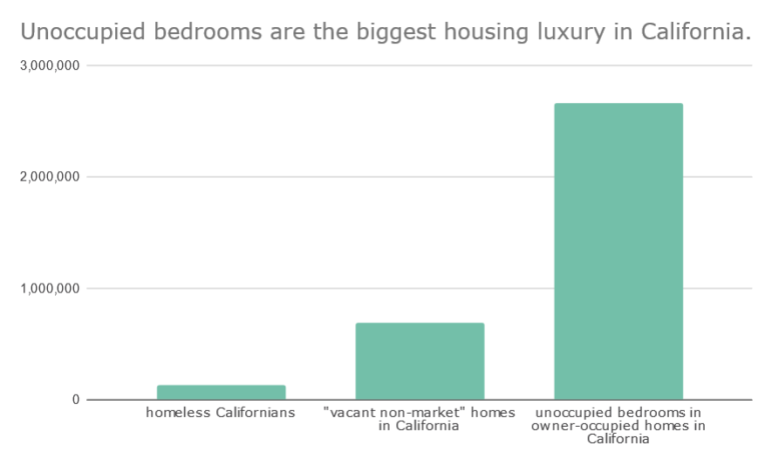

It’s true that for 2013-2017, the Census estimates 691,343 totally empty homes in California, including plenty in condo buildings, that ACCE categorizes as “off-market” because they’re either “for seasonal, recreational or occasional use” or otherwise unavailable to rent or buy. This is, disturbingly, more than five times the estimated 129,972 homeless Californians.

It is equally true that even if every adult and every child in one of California’s owner-occupied homes required a bedroom of their own, the state would have 2,660,505 bedrooms where no one sleeps—20 unoccupied bedrooms for every homeless Californian.

One of these inequities is much, much larger than the other.

Not only is California failing to disincentivize this second, larger injustice. In this case, it’s actually subsidizing the injustice with hundreds of millions of dollars every year in the form of California’s cap on property taxes for longtime property owners, which swells the price of housing for anyone not lucky enough to already own.

Not only is California failing to disincentivize this second, larger injustice. In this case, it’s actually subsidizing the injustice with hundreds of millions of dollars every year in the form of California’s cap on property taxes for longtime property owners, which swells the price of housing for anyone not lucky enough to already own.

This isn’t a call to disregard ACCE’s valid criticism of how some homes, including some in condo towers, can sit empty while humans struggle to survive outdoors. (ACCE later pulled the report from its website over problems with a mostly unrelated section of the project that looked specifically at recently constructed buildings; I don’t discuss that problematic section in this article.)

But for Californians (and for Cascadians playing out similar debates) it’s worth asking: Why does the smaller of these two inequalities seem to persistently get more political attention than the bigger one?

And who benefits as a result?

The renter’s shortage, the owner’s surplus

Forty-five percent of Californian households have no such surplus of space: the 45 percent who rent their homes.

Unlike with owned bedrooms, California doesn’t have enough rented bedrooms for every renter. Even if you were to assume that Californians share bedrooms at the same rate as British Columbians (Canada has more precise data on bedroom sharing) only about 4 percent of tenant bedrooms in all of California are unoccupied at night.

In housing-scarce Los Angeles, home to ACCE, things are even tighter for renters: they’ve got fewer bedrooms per person even than British Columbian tenants. And one bedroom per tenant is a distant dream for Angelenos. To do that, the city would need 20 percent more rental bedrooms.

This is how a housing shortage affects its losers: they squeeze tighter and tighter together if they can find anything at all.

Not so in the Los Angeles ownership market, which has about 90,000 more bedrooms than Angelenos. If Angeleno homeowners are sharing bedrooms at BC homeowner rates, it’s more like 160,000 bedrooms, 11 percent of the total owned bedroom count. That’s compared to (in the 2013-2017 Census data) about 46,000 totally vacant “off-market” homes in Los Angeles and 36,000 Angelenos without homes.

Most of these unoccupied bedrooms, of course, have been rising rapidly in value, thanks to the state’s continuing failure to build enough total homes to keep up with job and population growth.

The market price of housing varies wildly by state and (because more than 75 percent of low-income Americans live in market-rate housing*) correlates directly with the rate of homelessness.

What’s to be done?

No, I don’t think it would be a good idea to appropriate every guestroom in Orange County and house homeless people in them. ACCE isn’t calling for empty condos in Beverly Hills to be seized, either. (Satisfying though that might be in some cases.)

Instead, like ACCE, Californians and Cascadians and everyone else should look for structural changes—economic dikes and sluice gates that would channel our wealth away from waste and toward voluntary, abundant sustainability.

In addition to continuing to raise and spend money for below-income housing, we should do things like re-legalizing shared homes, lifting the apartment bans in low-density, job-rich enclaves of San Jose, subverting speculation with community land trusts and reforming California’s monumentally terrible property tax system that systematically transfers wealth from young to old, migrant to incumbent, brown to white. All these things would lower the costs of finding a stable home in California.

And in the meantime, I hope that when we use housing inequality to focus on the need for change, we don’t overlook the single biggest form of luxury in our housing market: big detached homes whose residents aren’t even really using all the space.

* This is a conservative estimate based on 2012-2016 Department of Housing and Urban Development data, the most recent available, and the 2015 American Housing Survey. Adding all households in HUD-subsidized rentals together, and assuming that all US households in subsidized housing are low-income, suggest that at most, 14 percent of all low-income households could be in HUD-backed housing. The 2015 American Housing Survey estimates that 7.2 million units in the US are subject to government rent reductions, including state and local programs; this is 23 percent of low-income households. (I considered a US household “low-income” if its income was less than half the median calculated for its area, as tallied nationwide in HUD’s Comprehensive Housing Affordability Strategy data. Many state and local programs subsidize people with somewhat higher incomes, so this 75 percent figure is probably an underestimate.)

Comments are closed.