For three years, Portland’s proposal to re-legalize fourplexes citywide has been overshadowing another, related reform.

That other reform applies not to low-density lots but to mid-density areas: The ones currently zoned for townhomes and small to medium-size apartment buildings. It’s finally coming before Portland’s city council in a public hearing Wednesday. (The city is also accepting online testimony right now.)

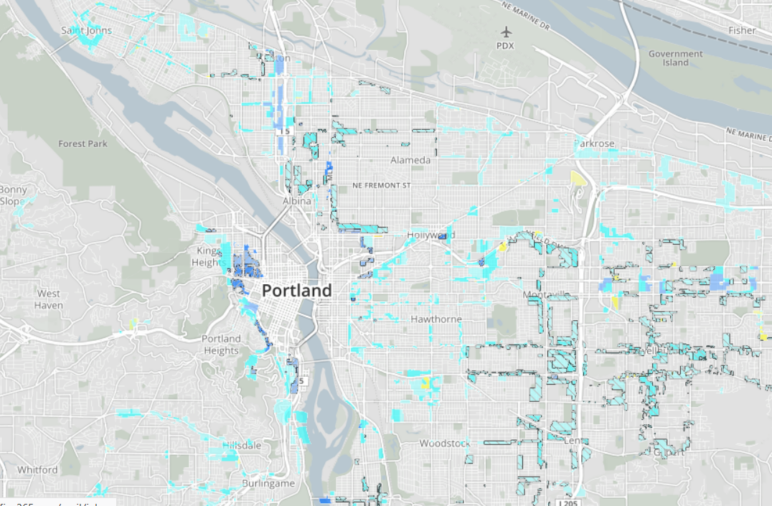

Lots affected by Portland’s “Better Housing by Design” reform to mid-density residential zones. Image courtesy of Portland Bureau of Planning and Sustainability. Map generated by Esri.

This proposed mid-density reform, dubbed “Better Housing by Design,” includes various good ideas, like helping East Portland’s big blocks include shared interior courtyards; regulating buildings by size rather than unit count; and giving nonprofit developers of below-market housing a leg up with size bonuses.

But one detail in this proposal is almost shocking in its clarity. It turns out that there is one simple factor that determines whether these lots are likely to eventually redevelop as:

- high-cost townhomes, or as

- mixed-income condo buildings for the middle and working class.

The difference between these options is whether they need to provide storage for cars—i.e. parking.

According to calculations from the city’s own contracted analysts, if an average of 1.5 off-street parking spaces per stacked condo unit were required in the city’s new “RM2” zone, then the most profitable thing for a landowner to build on one of these properties in inner Portland would be 10 townhomes, each valued at $733,000, with an on-site garage.

But if off-street parking isn’t required, then the most profitable thing to build is a 32-unit mixed-income building, including 28 market-rate condos selling for an average of $280,000 and four below-market condos—potentially created in partnership with a community land trust like Portland’s Proud Ground—sold to households making no more than 60 percent of the area’s median income.

This is worth repeating: As long as parking isn’t necessary, the most profitable homes a developer can build on a lot like this in inner Portland would already be within the reach of most Portland households on day one.

But if we require parking on these lots, we block this scenario. If we were to require just one space for every two condos, the most profitable building would be more expensive condos with zero below market homes. And if stacked flats had to come with 3 parking stalls for every two units, the most profitable thing to build becomes, instead, a much more expensive townhome.

When people say cities can choose either housing people or housing cars, this is what they’re talking about.

Fellow nerds: Here are the numbers

Here’s the math, as calculated last year by real-estate economics firm EPS Inc.

First, some necessary jargon: “stacked flats” refers to a series of one-level condos on top of each other, arranged in a building looking something like this:

Image courtesy of Portland Bureau of Planning and Sustainability, used with permission.

“Townhomes” refers to homes attached to each other at the side, looking like this:

Image courtesy of Portland Bureau of Planning and Sustainability, used with permission.

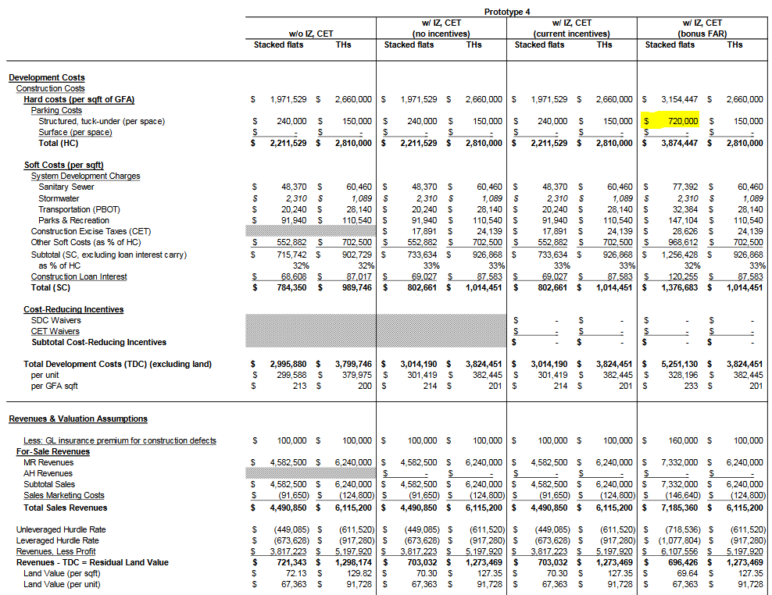

We’re interested in what the analysts referred to as “prototype 4”: a hypothetical 100’x100′ lot (maybe assembled from two or more smaller lots) in the new RM2 zone in an “inner neighborhood” of Portland. EPS ran numbers on a “stacked flats” condo project and a “townhomes” project on this lot. (They considered rental homes, too, but concluded that occupant-owned homes would be a bit more financially feasible in this zone than rental homes.)

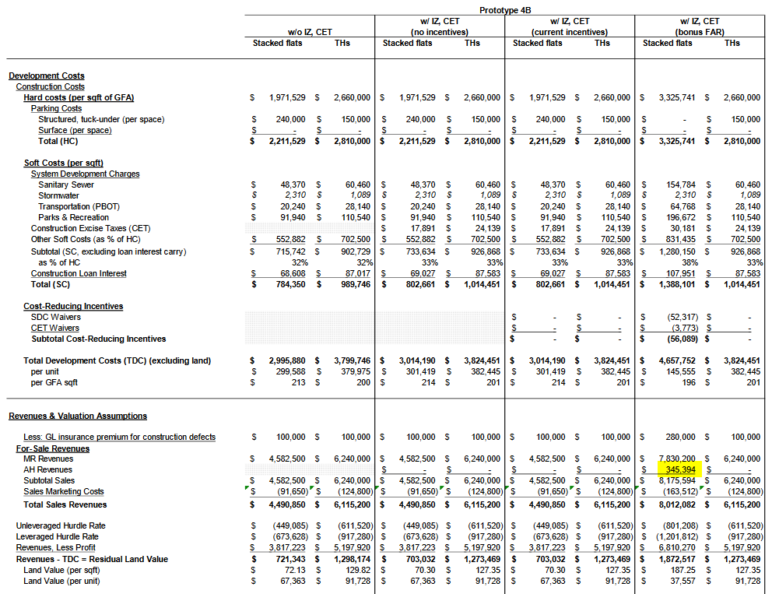

First, EPS added up the costs and probable revenues of such projects if they have parking. You can see their estimates in the rightmost column of the table below. (The other columns refer to different regulatory scenarios.)

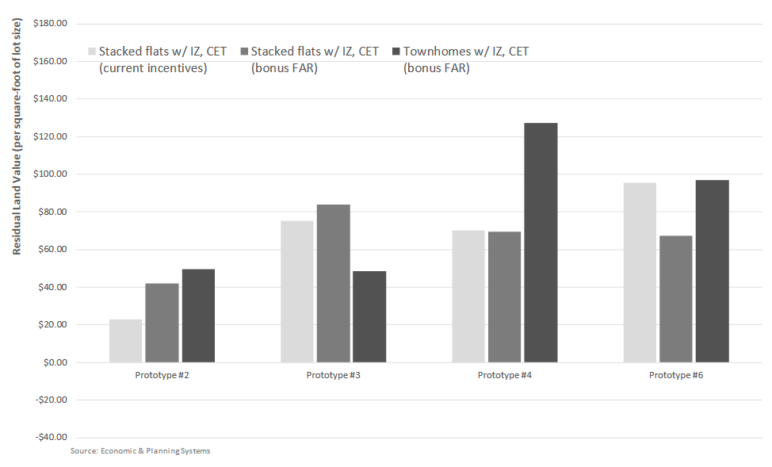

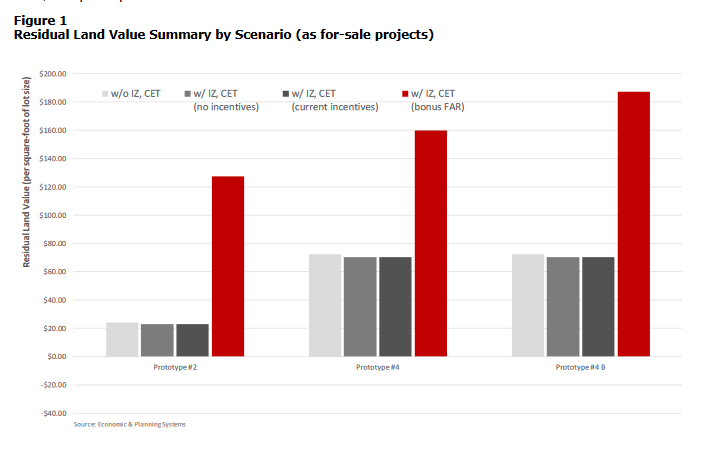

Check out the number I highlighted. If someone tried to create 1.5 parking spaces for each stacked-flat home on a lot like this, they’d end up having to pour almost three quarters of a million dollars into a 24-car garage: Well, it turns out that constructing a small apartment building with a $720,000 garage is an unprofitable business venture. EPS calculates that this additional expense would sink such projects. The likelier outcome would instead be 10 much more expensive townhomes, which is the project type represented by the tallest bar below:

Well, it turns out that constructing a small apartment building with a $720,000 garage is an unprofitable business venture. EPS calculates that this additional expense would sink such projects. The likelier outcome would instead be 10 much more expensive townhomes, which is the project type represented by the tallest bar below:

Then the analysts flipped one switch—the presence of parking—and everything else changed, too.

See the number I highlighted in the revised table below, “AH revenue”? That’s the amount of money the developer would be bringing in, total, from the four “affordable housing” homes under the parking-free scenario 4B. Notice how none of the other scenarios include that figure? That’s because none of the other scenarios here would create any below-market housing. This project would.

Notice how none of the other scenarios include that figure? That’s because none of the other scenarios here would create any below-market housing. This project would.

The parking-free stacked flats scenario (4B) still includes market-rate homes too: 28 of them in this case. But if you look at the number immediately above the one I’ve highlighted, you’ll see the developer would be bringing in about $7.8 million total from those homes—an average of $280,000 each.

With 20 percent down and a mortgage interest rate of 3.9 percent, that comes out to a monthly payment of $1,390, including taxes and insurance, for a small, newly built home in inner Portland.

And—I’m just going to point this out a third time—this building full of middle- and working-class homes would be the most profitable thing someone could build on this land, as shown by the rightmost bar below: That’s a lot of charts and figures.

That’s a lot of charts and figures.

But for the people who would live in these homes, having a stable home they could afford in central Portland would be an extremely concrete blessing in their lives. Even if it means parking their car, if they have one, on the street.

Many projects will include parking, but that doesn’t mean the city should require it

The bad news is that it’s far from certain that many developers—or, more to the point, the banks that issue developers’ construction loans—would actually choose to build 32-unit buildings without off-street parking. It just isn’t easy enough yet to get around Portland without a car.

If banks decide they simply have to have lots of off-street parking in order to sell these homes, goodbye stacked flats; hello townhomes. Goodbye, affordable community land trust homes. Goodbye, market-rate homes for the middle class.

That’s depressing, and it’s one of the many reasons cities should be investing heavily in making low-car life possible for more people.

But Portland is currently proposing something downright foolish: It wants to keep requiring garages on some of these lots. The mandate would apply to any lots that are more than 10,000 square feet, more than 500 feet from a frequent-service bus stop, and more than 1,500 feet from a rail stop.

As the numbers above show, the city may as well be banning below-market housing from many lots that don’t meet that standard, including lots that may be zoned “RM2” in the future. And every lot where the city requires parking shuts the door to future entrepreneurs who might come up with creative ways to help people avoid car ownership.

More broadly, there’s an issue of principle here that could apply in any city: Mandating off-street parking, even when we’re fully aware that it makes more and cheaper homes impossible, requires a judgment that housing cars is more important than housing people.

Nowhere in Portland—nowhere on the planet—is that true.

Take it from Portland’s mayor, Ted Wheeler, who said the following a few months after coming to office:

“I want to put a marker down. The debate: Parking vs. Housing? It’s really over. That piece of the conversation is over. When younger families or younger people say they want to locate here, the first thing they’re saying isn’t ‘Boy I wish I had another parking space, or had access to a parking space.’ What they’re saying is, ‘I can’t afford to live in this city.’ And, so, the city, meaning the debate that happened over the last three years actually made a choice, and the choice was affordability and housing over access to parking. I just want you to be aware that that is a real dynamic and is a real choice and it was made with full community involvement.”

I don’t always agree with Mayor Wheeler. But I can’t disagree with any of that.

Correction 10/29: An earlier version of this post repeated several errors that stemmed from a clerical error by EPS, the city’s consultants on this project. EPS had described their model for townhomes as reflecting a 1:1 parking ratio rather than the 0.5:1 ratio actually modeled by the rightmost column in the first table shown above. EPS had also described their model for stacked flats as reflecting a 0.5:1 parking ratio rather than the 1.5:1 ratio actually modeled. If EPS’s models had used the ratios promised in their narrative, they would have found these results for “prototype 4” instead: assuming the market does not demand on-site parking, 32 stacked flats without parking would be most likely to be built, followed by 19 stacked flats without parking, followed by 16 stacked flats with parking (at 0.5:1), followed by 10 townhomes with parking (at 1:1).

So it’s still parking that determines which scenario is most likely, but the switch from townhomes to flats occurs at a different parking ratio than the earlier version of this post claimed. EPS has confirmed these revised figures. Thanks to reader Judi Draper for calling this to our attention in the comments below.

Tim Duncan

It’s not an either/or scenario. It’d be dishonest to assume that people in condos won’t have cars or have visitors with cars. Delivery vehicles need somewhere to go.

If the city does not mandate parking for new development, the developer will happily offload the parking onto city streets. The city and its citizens end up paying for the parking.

CM

Ban parking on public streets.

Michael Andersen

What’s your new plan for that space?

Marti L. Bridges

Relying on street parking is bogus. Boise has done this and it’s a nightmare. Every home or Apartment should have parking, preferably under ground or the first two building floors. I’ve found few cities with a grocery store nearby in Downtown you can afford or walk to. A minimum of parking for one -2 vehicles is indeed necessary.

Sherri Schultz

Very helpful article and awesome number-crunching, but I have to take issue with the curious statement

WTF??!! Since 1981, I have lived a happy and full car-free life in Eugene, Oregon; Washington, DC; Seattle; and San Francisco. Portland is no different than these other cities, and is arguably superior to some. I have visited Portland many times, using Max, TriMet, Uber, Lyft, and of course my feet to get around. It is marvelously easy. Please re-examine this puzzling assertion, as buying into it undercuts the excellence of your work.

Sherri Schultz

[reposting, since this platform doesnt like angle brackets]

Very helpful article and awesome number-crunching, but I have to take issue with the curious statement “It just isn’t easy enough yet to get around Portland without a car.“

WTF??!! Since 1981, I have lived a happy and full car-free life in Eugene, Oregon; Washington, DC; Seattle; and San Francisco. Portland is no different than these other cities, and is arguably superior to some. I have visited Portland many times, using Max, TriMet, Uber, Lyft, and of course my feet to get around. It is marvelously easy.

Please re-examine this puzzling assertion, as buying into it undercuts the excellence of your work. Cheers from Eugene (again).

Michael Andersen

Sherri, good feedback! Maybe it would have been more accurate for me to say that “it isn’t hard enough yet to get around Portland with a car.”

I lived car-free in Portland from 2010 to 2014, at which point my now-wife moved in with her ancient Honda. (I’m not counting car-sharing … one could also say that I have had hundreds of cars at my disposal the whole time.) There is no question that fulfilling car-free lives are possible in Portland. Tens of thousands of us live them, though not always by choice of course–many Portlanders don’t have the means to buy a car if they wanted one.

We live near the NE 60th Avenue MAX stop, with nonfrequent north-south and east-west bus lines a few minutes’ walk away, so we’ve got better transit access than the average Portland household. But the main reason we own a car is that my wife works nights at OHSU, and when she gets off a 12.5-hour shift, a car is the difference between a 12-minute commute home and a 45-minute bike-to-transit trip home. That’s an hour per day, which is quite a lot of the 3.5 hours she has on those days to spend doing something other than working or sleeping.

She probably won’t work nights on the hill forever. And we won’t have a young kid (our other main reason for car ownership, especially when he was a baby) forever. I hope future phases of our life will let us return to almost exclusive use of foot, bike and transit. But until more transit trips can compete with car trips, and/or until everyone has an ebike, it’s hard for me to imagine very many Portlanders who can afford a $730,000 townhome choosing not to own both a car and a garage. Even in neighborhoods like ours.

t ashoff

I am the proud user of an uncrowded and safe for kids NE street because of off street parking – which now is turning into a park and ride for suburban employees. I sure am glad I can plug in my LEAF in a garage without having it messed with at night.

asdf2

I was recently house-hunting in Kirkland and, somewhat ironically, the combination of not owning a car and moving to the city with excessive parking requirements *increased* my willingness to pay a premium for an individual garage.

Basically, thanks to excessive parking requirements, the only alternative to a garage was paying for 300 sq. ft. of parking spaces in a shared garage, which I could not use. In Kirkland, a private garage is the only way to convert your city-mandated parking spaces into space which is good for anything other than storing cars.

After moving in, I have managed to get good use out of the garage space. I use it to store multiple bikes, all my biking accessories, and other tools. I will say that it is extremely convenient having your bikes in a garage, ready to go, rather than tucked away in a storage room, where just getting the bike out onto the street can take more time than the bike ride itself.

Michael Andersen

I totally agree, garages are perfect for storing bikes. (Better than they are at storing cars, actually?) My family owns both a car and three bikes, and it’s annoying that we no longer have an on-site garage to put the bikes in.

But the reason we don’t have an on-site garage is that our friends/landlords knocked it down to build the backyard cottage we now live in. If we didn’t have a home, I would find that much more annoying!

Shane

What about the livability of the neighborhood with the impact of 32 cars now crowding into street parking? There’s just about enough street parking in my neighborhood as it is, jamming 32 more cars in would decrease the satisfaction of living. It’s fantasy thinking people are going to give up their cars if there’s not a garage. True, some people are car free, and I applaud them, however, there’s no way you build 32 units and not one person living there has a car.

Michael Andersen

The public owns the street. However many cars these residents may own are only annoying to me if I, too, am looking to park in the public street (my own family does indeed do this, for the record). Why am I any more entitled to use that space than they are, especially if the cost of preventing this annoyance to me would be that their homes wouldn’t get to exist?

The fact is that Portland (like all large US cities) has tens of thousands of garages and driveways that aren’t being used for car storage. This is because thousands of acres of public curb space are made available for free to store exactly one type of object: the car. So people do. If scarcity of curb space becomes annoying to us, we could use permits to start controlling that public space. That would motivate people to clear out their garages and park there, and it would obligate developers to build adequate off-street space. But until you’re willing to use a permit system too, I don’t think you have a very strong argument to make.

Cam

I may have missed this, but I’m curious about the _size_ of the apartments in the condo building. This analysis seems to take into account only the per-unit price, ignoring the per-bedroom price.

A townhome will actually make for much cheaper per-person housing if an entire family, multi-generational family, or group of 3-6 renters is occupying it. This is because in my experience (in Seattle) condo and apartment buildings are almost exclusively studios and 1-bed apartments, with occasional 2-bed units.

As an example, my family is myself, my wife, and our daughter. Our in-laws frequently come to live with us. We would actually prefer to live in an apartment but apartments with 3+ bedrooms are extremely rare in Seattle, so we settled on a townhouse.

Interesting stuff, thanks Michael!

Michael Andersen

This is a totally fair point: the condos in this model are 600 sqft (so fine for a couple interested in prioritizing location rather than size, but pretty tight for 3+) whereas the townhomes are 1900 sqft (quite a bit larger than the median detached home in Portland today, which is probably more like 1100).

But the thing is: we *want* people, especially people who can scrape together the cash for a 600 sqft condo but not for a 1900 sqft townhouse, to at least have the option prioritize location rather than size. That’s how we enable voluntary carbon reductions. In the long run, that’s part of how we integrate our schools and neighborhoods by wealth and race.

I think we still need to build some larger homes. But at least in Pacific Northwest cities, the shortage of small homes for 1-2 person households is far more acute than the shortage of large homes for larger households — that’s why so many people are in involuntary co-housing situations in shared larger homes. The families those larger homes are really designed for were priced out by groups of 3+ renters who could bring in more income per bedroom.

Therefore our affordability strategy for large homes shouldn’t be to deter the building of small homes — it should be to build enough small homes that more of those involuntary co-housing situations can afford to split up into multiple households, which will free up more of the larger homes for larger families.

Got a piece on this in the works right now.

Chris Carlton

Well… That’s a huge disparity in size and function, with the condo costing more per sf, especially if you add the garage area to the townhouse’s 1900.. I want reasonable zoning solutions, but separately, we have to get building regulations, accessibility standards, and the rest sorted out or we will still be hurting. Building taller and bigger isn’t usually cheaper.

Michael Andersen

Smaller homes will always cost more per sqft until we stop requiring all of them to include their own kitchen and bathroom! Though we should be doing everything within safety and reason to cut the hard cost of construction, unfortunately there’s no magic wand that makes the construction process inexpensive.

The best we can do is to (a) build enough new stuff that prices remain stable for the older stuff and (b) make a variety of unit sizes legal in every neighborhood, to give people the option to live in small but conveniently located homes if that’s their preference.

Ernest

Thank you so much Michael, for performing and sharing this analysis.

In addition to highlighting a very specific instance in which the city is literally choosing cars over people, I believe your work also illustrates why it’s vital that the issue of livability/housing affordability be considered as part of a holistic plan for the city.

For example, I believe it’s right for the city to include building requirements tied to the availability of public transit (though I think the “500 feet from a frequent-service bus stop” provision is overly restrictive). As several commenters have mentioned, absent easy access to public transit, eliminating off-street parking will amplify issues of on-street congestion. So this provision also helps to highlight how far we still have to go in terms of our public transit infrastructure.

But this is a classic chicken-or-egg scenario: If we wait until our public transit infrastructure is built-out to enable the development of more affordable housing, neither is ever going to happen, because we’re not going to build-out the public transit infrastructure until the demand exists to justify it. So it seems clear that the housing HAS to come first. It means we’ll have to deal with some headaches while we wait for transit availability to catch up to housing density, but the former won’t happen without the latter. I wish someone in city leadership would advocate for this in an open and honest way.

On a somewhat related note: This also highlights to me the madness of our city investing so much in light rail. The billions that have been spent on a handful of fixed service light rail lines could have, instead, funded a robust city-wide bus network with bus-only lanes along key thoroughfares. Yet, still, instead of expanding access through buses, our leaders continue to funnel billions of dollars into extensions of light rail, including the insane boondoggle that is the Barbur MAX extension.

These decisions all go together: By diverting funding to these handful of showpiece light rail lines, we’re limiting access to affordable public transit, which is in turn limiting the develop-able area for affordable housing. If we continue to look at these decisions in discrete silos—transit is transit; housing is housing; homelessness is homelessness—we’re never going to be able to solve these big issues that will only become more acute in the decades ahead.

Oh well, enough soapboxing from me—thank you again for sharing this!

Judi Draper

Nice analysis but unfortunately the EPS paper on which it relies has some faulty math.

According to page 4 of the source document EPS stipulated $30,000 per tuck-under parking space even when podium-style construction is used. Parking spaces were allotted with a ratio of one space for every two units of stacked flats and one space per one unit of townhome. The parking space costs should then be $300,000 in each of the Prototype 4 townhome estimates and $150,000 for the first three Prototype 4 stacked flat estimates with the final stacked unit estimate at $240,000 based on slightly higher unit density in that example. There were other math errors present in the EPS paper but that was the most glaring. I read the entirety of what was linked and did not find any explanation for why the numbers as presented may have differed from what was expected. If they have amended their work with updating calculations, I apologize as I only had what was linked from which to work.

While I am all for choosing housing and people over cars, I think that to argue our case with wobbly data will be damaging.

Michael Andersen

Thanks for this, Judi – I agree with you about wobbly data. I just sent you an email in hopes of getting to the bottom of any errors here, and will correct the post above as necessary if there are in fact problems.

Michael Andersen

Thanks again for this and our email exchange, Judi. As the article now notes (with thanks to you), I’ve corrected the post to reflect these errors by EPS.

Theresa Cashion. tntcash3535@aol.com. Without this,years before this area will be no different than the projects. Theresa

Will these areas be for adults only? I ask this because the drawing shows building to building with almost no land area. Will there be parks across the street? Or perhaps you think it’s OK for children to live indoors all the time. This idea appears to be a pie in the sky because the two very important issues are ignored. Cars parked somewhere and young people having some outdoor spaces are essential to quality living. Without this, it will not be many years before this area will be no different than the projects. Theresa

Michael Andersen

As the father of a three-year-old and the resident of an ADU in a neighborhood that lacks either a park or a public school, I will say that I completely agree that kids need outdoor time. I’ll also note that in Portland, every new home built contributes between $5,118 and $14,633 to local park development, depending on size, in addition to its future property taxes.

If I had to choose between spending my $10,000 on 100 additional square feet of backyard or on my share of getting a park in my neighborhood, you bet I’d rather have the park. That’s how every city does it as it fills in, isn’t it? Open space shifts from private to public for the sake of greater efficiency.

If Portland were running short on homes with yards, I might be more concerned. Instead, what it’s short of is homes for the many more small households without kids that we, like every city in the developed world, has added in the last 60 years or so.

https://www.sightline.org/2019/12/12/we-need-homes-of-all-sizes-but-our-main-shortage-is-of-small-ones/

Juanita Ross

If your talking about low income housing yes not everyone owns a car.but those same people cant afford to take a lift bus everytime they need to go grocery shopping either.not counting having to possibly walk two blocks or so to unload your car or 5 blocks to carry groc.from a bus stop.or taking kids to the dr.and should a person have guest not being able to even find a parking space at all.if you have an urban neighborhood with one story houses you come out to find car stolen or parts stripped off your car.on the street I live they had to put bumps in the road to slow people down so kids were not hit and killed anymore.so if you add a lot of parked cars it that much easier for kids not to be seen.lwt alone the stress on sewer in those areas.i dont think these kind of buildings should be allowed to be built in one ore story dwelling areas. At all thank you J R