Critics of congestion pricing argue that the policy favors the rich and hurts the poor. A new proposal to break gridlock in downtown Seattle offers a progressive approach to get traffic moving. Few low-income households would pay the toll and the revenues from higher-income households could put free, multi-modal transit passes in the hands of low- and moderate-income people who travel to downtown.

Workers in downtown Seattle—Cascadia’s biggest jobs hub—who earn less than the median income of $35 per hour would, as a group, receive more money for mobility than they would pay in tolls and transit fares, according to the proposal. They would also waste less time stuck in traffic because commute speeds would increase by as much as 30 percent.

Washington has the most regressive tax system in Cascadia or, in fact, anywhere in the United States, so any plan to make transportation fairer and faster should get a close look. Because of Washington’s exclusive reliance on sales, gas, excise and property taxes, the poorest 20 percent of households spend nearly 18 percent of their income on those taxes while the wealthiest 1 percent pay just 3 percent.

In 2014, state and local governments within the four counties of central Puget Sound levied $7.8 billion in taxes to pay for roads, transit, and ferries that fell most heavily on the poor. With gas tax revenues projected to fall because of rising fuel efficiency and vehicle electrification in the next decade, the region needs a new approach. Fortunately, one has recently emerged. It’s called Fair and Efficient pricing and it’s the brainchild of Matthew Kitchen of ECONorthwest, a local economic consulting firm.

Kitchen used to work at the Puget Sound Regional Council (PSRC), which develops long-term transportation plans, so he knows his way around the regional data. He took an enormous dataset of regional trip-making behavior from PSRC and combined it with new public data from Uber (the study sponsor) on hour-by-hour travel speeds on the street network. He mixed in local research on how drivers respond to price changes and insights gathered from other toll projects across the country.

From all the number crunching emerged a picture of how Fair and Efficient pricing could work in Seattle:

- Auto travel time to and from downtown would decline by 30 percent during the morning and afternoon commute.

- Bus transit speeds would increase, and so would ridership. Consequently, transit trips into downtown would increase by 4 percent, even without investments in new transit service.

- Auto trips during commute hours would decline by 7 percent.

- Tolls would range from zero on weekends, between 11 pm and 5 am on weekdays, to $1.50 at midday to $3.80 during the afternoon rush hour.

- Drivers would only pay once, for the most expensive hour the vehicle traveled within downtown. The maximum charge any private vehicle would pay per day is $3.80. Uber, Lyft, and taxis would pay a charge per ride delivered.

- The program would generate at least $130 million per year in gross revenues.

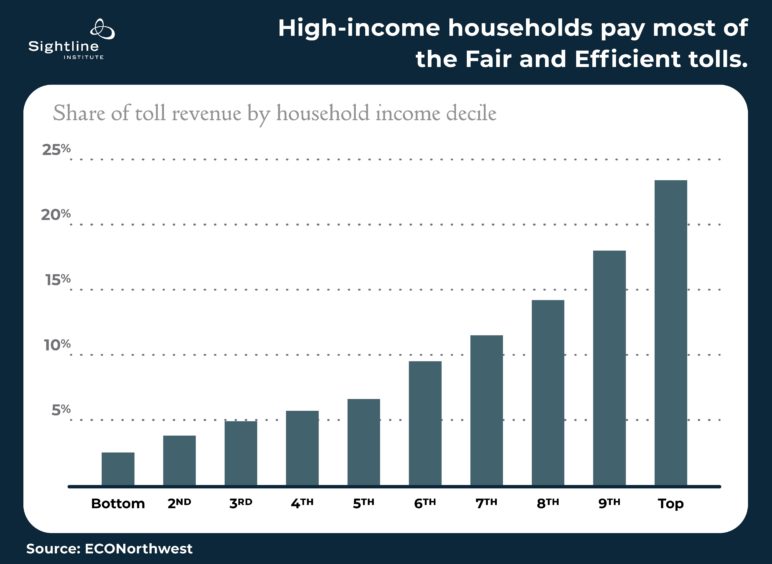

The analysis also shows that high-income households would pay most of the toll revenue, which makes sense because high-income drivers make up a disproportionate share of the auto trips into downtown.

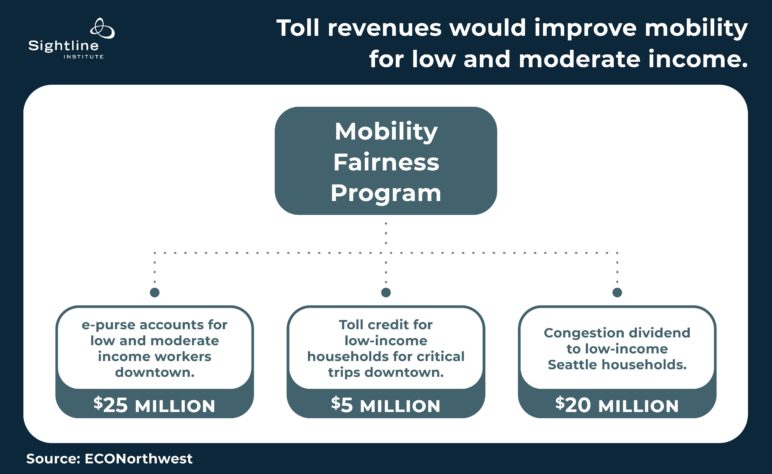

But for those households earning less than the regional median income (the left half of the chart above) who need to drive into downtown, the toll rates would still represent a larger share of their income than for the higher income groups. To stem this regressive element of tolls, the Fair and Efficient plan devotes $50 million of the more than $130 million in gross revenue to fund a three-part Mobility Fairness Program.

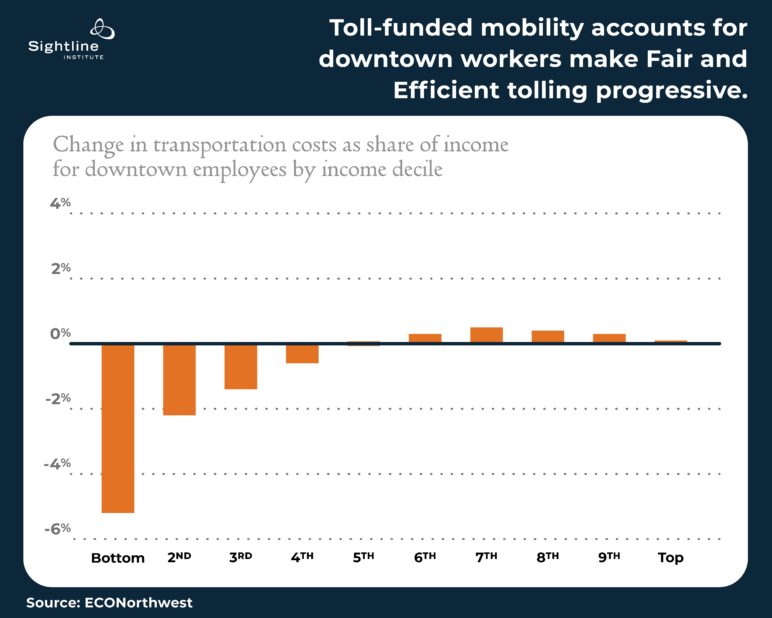

The first part involves all employers with workers in the downtown area administering a new transportation benefit for employees whose incomes are near, or below, the regional median. Think of it as an e-purse or super Orca card of $85 per month that can pay transit fares, bike-sharing expenses, shared-ride fees, parking charges and tolls. Workers downtown who earn less than $35 per hour would receive toll revenues back in the form of the super Orca card independent of whether or not they pay tolls. For workers who pay the toll daily to enter downtown Seattle, the e-purse would offset daily toll expenses. For workers who avoid the toll entirely by taking transit, the super Orca card would represent new money in their pocket.

The second part of mobility fairness would provide rebates to offset toll charges associated with important trips into downtown by low-income households that qualify for programs such as Medicaid or the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. Hospitals and other essential service providers would validate visits by qualifying households so they can receive a credit on their toll payment account, much in the way some medical providers validate parking in nearby garages. Finally, some 30,000 Seattle households with the lowest incomes that qualify for the city’s utility discount program would receive a super Orca card worth $50 each month to ensure better mobility for the low-income.

For low-income workers downtown, the Mobility Fairness Program would represent a meaningful decrease in costs. For those earning close to minimum wage, the value of the super Orca card after subtracting what they would pay in tolls is more than 5 percent of their annual income.

This new study lands just weeks after the City of Seattle published its Phase 1 summary report that surveyed the lessons from other cities that have implemented congestion pricing solutions. The Fair and Efficient plan offers a promising approach that cuts congestion and improves equity that the city will want to consider as it moves into discussion with community stakeholders about next steps.

Polling shows little enthusiasm for congestion pricing now. But experience in cities that implement pricing shows public opinion can flip from opposition to support when the benefits become obvious. A plan that cuts traffic by 30 percent and puts money in the pockets of low- and moderate-income workers could start to tip the balance in Seattle, setting an example for cities across Cascadia and beyond.

Disclosure: Uber has authorized a grant to Sightline Institute to underwrite a portion of an effort to convene stakeholders in Seattle to discuss congestion pricing. Daniel Malarkey served as a third-party reviewer of an early draft of the ECONorthwest study described in this blog post.

Editor’s note: We’ve clarified the article to reflect what type of vehicle would pay for rides downtown in the fifth bullet point that spells out how Fair and Efficient pricing could work in Seattle.

Comments are closed.