[vc_row][vc_column][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner][vc_column_text]It’s official: Cloud Peak Energy, the Powder River Basin coal giant, declared bankruptcy on Friday, May 10.

And in what may turn out to be one of its final quarterly financial filings, the company revealed that it suffered through a brutal first quarter. Cloud Peak hit a trifecta of awfulness—slumping sales volumes, skyrocketing production costs, collapsing export prices—that, all told, yielded a $50 million accounting loss for the quarter, to go along with $31 million in cash losses from selling coal.

But Cloud Peak’s problems didn’t start last quarter, or even last year. The company—along with the rest of the “thermal” coal industry used to generate electricity—has actually been slouching towards insolvency for years.[/vc_column_text][vc_gallery interval=”0″ images=”71414,71413″ img_size=”large” title=”Gallery: Cloud Peak’s Demise”][vc_column_text]I’ve spilled more digital ink on Cloud Peak’s export business than I care to admit. Shipping coal to Asia generated some decent profits for Cloud Peak for a few years. But after the Pacific Rim coal bubble deflated, the company sustained major losses on exports, ultimately writing off hundreds of millions of dollars that it had invested in speculative export projects. It’s fair to say that the company would still be solvent if it hadn’t bet its nest-egg on Asian markets.

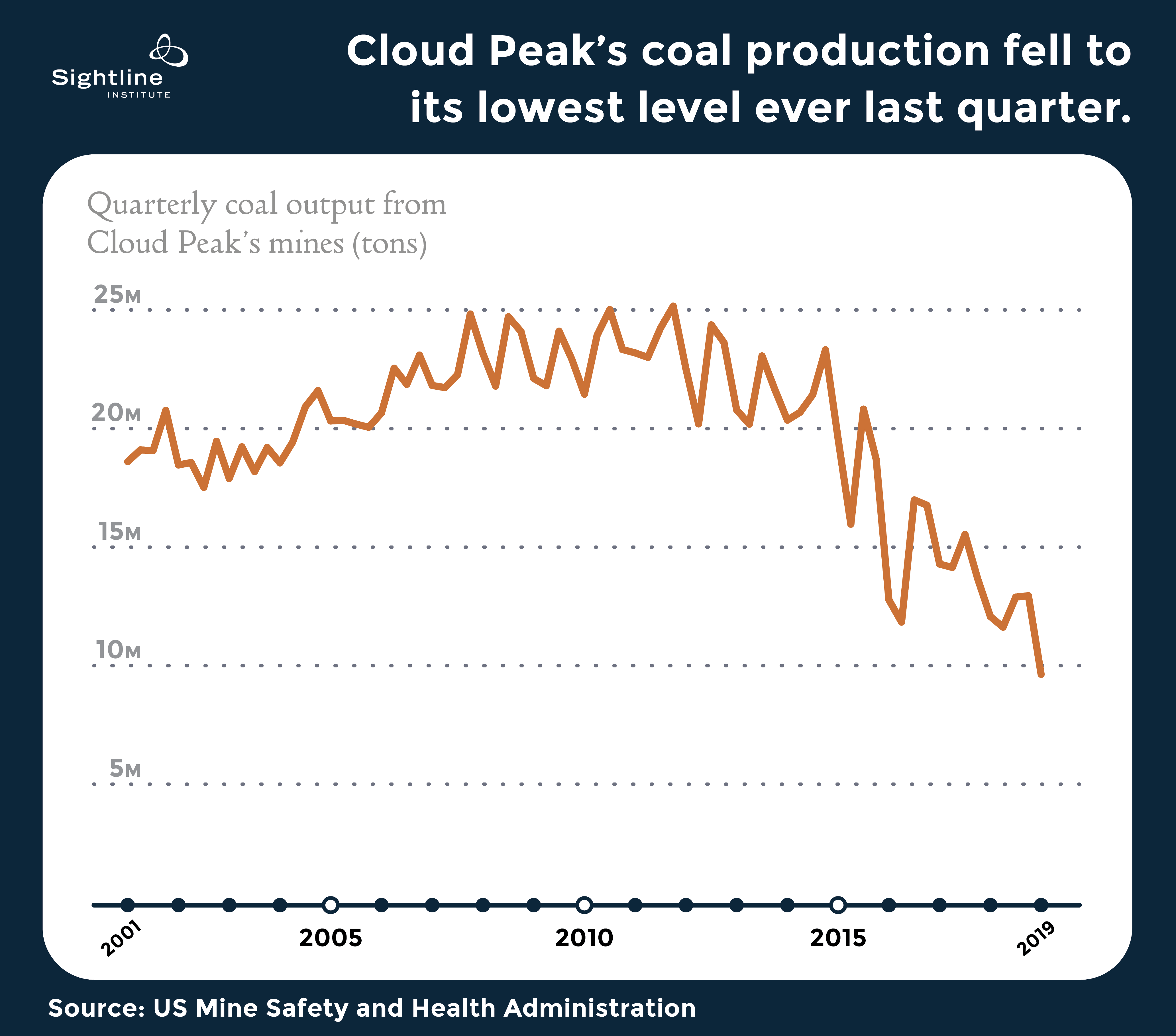

But it wasn’t just exports that sank Cloud Peak. The company’s domestic results have been just as gruesome. Production from Cloud Peak’s three massive mines in the Powder River Basin peaked in 2011, and have been in freefall since—and last quarter was far and away the worst in the company’s decade of existence. (Cloud Peak spun off from international mining giant Rio Tinto in 2009.)[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]Much of the decline in Cloud Peak’s production stems from rapid retirements in coal-fired power plants—not just any plants, but specifically the plants that are designed to burn the lower-energy “sub-bituminous” coal produced in the Powder River Basin. Last year was a big year for coal plant retirements in general. But for “sub-bit” retirements it was the biggest year ever (see the graphs above).

It’s impossible to blame last year’s wave of coal plant retirements on a politically motivated “war on coal.” The US coal industry had the robust support of the White House and the US Congress…and still lost more sub-bituminous power capacity than ever. The trend of coal plant closures underscores an important point: even with political support, coal just can’t compete in today’s electricity market. Renewables, electricity storage—and, distressingly, fracked gas—increasingly outcompete coal. At this point, it’s the electricity market itself that’s waging a “war on coal.”

Cloud Peak’s bankruptcy doesn’t mean that its mines will shut down. Yes, investors will lose a lot of money in the bankruptcy process. But the company’s mines will likely live to see another day.

Still, Cloud Peak’s insolvency is likely a taste of things to come for investors in the fossil fuel industry. It’s an industry that’s heavily in debt and wedded to an old way of doing business in an era of rapid technological and social change. As Cloud Peak’s story shows, that’s a perfect recipe for a financial implosion.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Comments are closed.