How much can onerous city rules hold people back from adding in-law apartments to their homes? Based on what happened in California, a lot.

At the start of 2017, a California state law went into effect that forced cities to relax their regulations on basement suites, garage apartments, and backyard cottages—known collectively as accessory dwelling units (ADUs). Two years later, building permits for ADUs in Los Angeles have surged by a factor of 30—yes, 30!—comprising a whopping one fifth of permits issued for all homes.

The pent up demand that’s driving Los Angeles’ ADU explosion may not be sustainable. But it clearly demonstrates the potential for ADUs to make a big contribution toward easing the housing shortages that plague so many growing cities.

The pent up demand that’s driving Los Angeles’ ADU explosion clearly demonstrates the potential for ADUs to make a big contribution toward easing the housing shortages that plague so many growing cities.

Meanwhile in Seattle, during the three years from 2016 through 2018—the height of the city’s building boom—just 2 percent of permitted new homes were ADUs. The long-running trickle of ADU construction motivated Seattle policymakers in 2015 to make it easier for homeowners to build them by liberalizing rules, but anti-housing activists filed appeals that have delayed passage of legislation for going on three years.

This year Washington state legislators also took up ADU reform to expand housing choices and help ease the statewide shortage of homes. The bill is currently wending its way through the legislative process, but at the time of this writing it appears unlikely that legislators will pass anything as forceful as California’s law.

The California story is a lesson for Washington: ambitious ADU reform at the state level works. Washington’s ADU legislation has sparked heated debate over local control of land use. But if cities would proactively adopt rules that welcome ADUs rather than treat them like a necessary evil, then they would have nothing to fear from a state law because it wouldn’t require them to do much, if anything. And then more homeowners and renters statewide could enjoy the benefits of these flexible, green, relatively affordable housing options.

What does California’s ADU law do?

In 2016, California passed statewide ADU reform in SB 1069, later tweaked in 2017 by SB 229 and AB 494. These laws require cities to:

- permit one ADU per single-family home

- streamline ADU permitting by using a ministerial rather than discretionary process

- set utility fees in proportion to the burden of the ADU and reduce them for ADUs built inside the main house

- waive parking requirements for ADUs located within a half-mile radius of a transit stop or within a block of a car-share; for ADUs built inside the existing primary house that don’t involve additions; and for ADUs in historic districts.

- otherwise require no more than one parking space per ADU, and allow that space to be tandem

- waive requirements for “passageways”—a commonly required ten-foot-wide, open walkway from sidewalk to ADU

- allow zero setbacks for existing garages converted ADUs, and five-foot side and rear setbacks for ADUs above garages

- cap ADU floorspace to 1,200 square feet for detached ADUs (backyard cottages); 1,200 square feet or 50 percent of house size, whichever is less, for an attached ADU that involves an addition to the main house; and no size limit for ADUs built entirely inside existing houses.

How the law played out in Los Angeles

SB 1069 set a January 2017 deadline after which cities that failed to update their ADU code to comply with the state law had to regulate ADUs using the state law as written. Los Angeles is one such city that missed that deadline, though it now has a new ADU ordinance in the works.

Because the state law is mute on requiring the owner to live on site when there’s an ADU on the property, Los Angeles cannot require owner occupancy, eliminating a major impediment to ADU construction.

The law also knocks down what is often the single biggest ADU barrier—parking. Because Los Angeles has a robust bus system, the state law’s waiver of parking quotas for transit proximity applies to most city land. That, along with the other prohibitions on parking means most ADU projects are not burdened with finding room for spaces on the lot and paying for their construction.

The ban on requiring passageways was particularly impactful in Los Angeles where houses are commonly laid out in a way that makes them impossible to fit. Homeowners building ADUs also benefit from relatively generous size maximums: 1,200 square feet for backyard cottages and no size limit for internal ADUs.

All told, the state’s ADU reform endowed Los Angeles an exemplary set of flexible rules. And the permit numbers show it, big time.

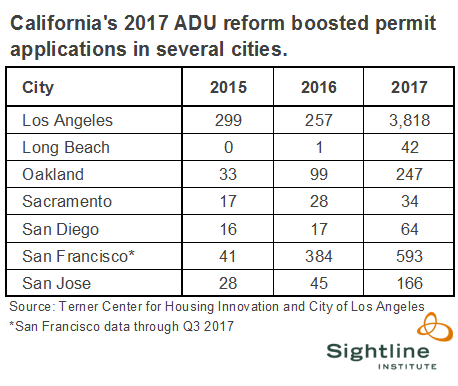

California’s ADU reform law boosted ADU production in cities across the state—especially Los Angeles

As we wrote previously, after the state’s ADU reform went into effect in 2017 permit applications rose dramatically in cities throughout the state, as shown in the table below.

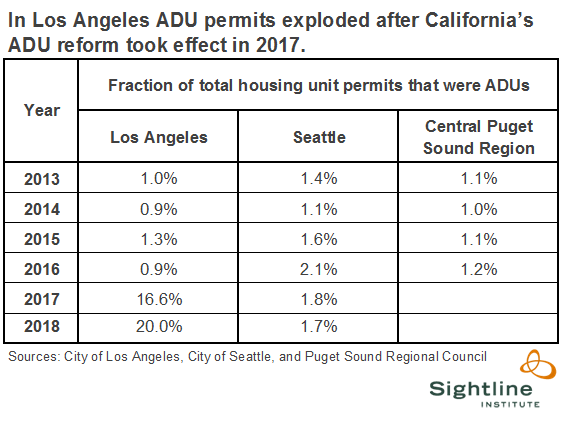

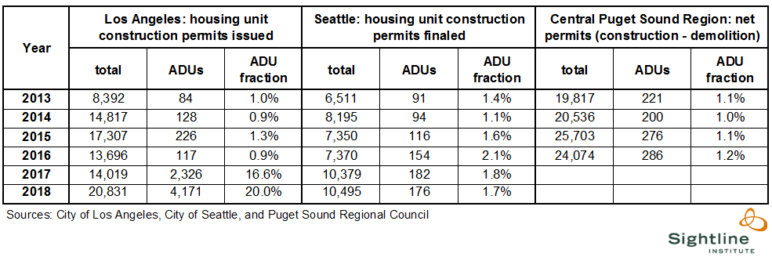

Zooming in on Los Angeles, the latest results are nothing less than spectacular. The table below shows the fraction of the city’s total construction permits that were for ADUs from 2013 to 2018 (see data notes for raw permit numbers). Prior to 2017, Los Angeles was permitting 100 to 200 ADUs per year. In 2017, ADU permits leaped to 2,326, and then in 2018 they nearly doubled to 4,171, accounting for one fifth of all permits. In contrast, in the years before 2017, ADU permits comprised a mere 1 percent of the total.

Some of the permitted ADUs may not be newly created homes—that is, they could have been functioning as ADUs already but not legally permitted—but it’s likely a small portion. In May 2017, Los Angeles launched a program to help owners get permits for existing, unpermitted ADUs that has so far approved 237 permits. About 45 percent of ADU permit applications in 2018 are for conversions within existing space in a house, but city planners believe that most are newly constructed ADUs.

ADU production in the Seattle area has limped along for years

ADU production in the Seattle area has limped along for years

As shown in the table above, in Seattle the fraction of permits issued for ADUs from 2013 to 2018 ranged between 1 and 2 percent. By that gauge, Seattle was doing slightly better than Los Angeles was before state ADU reform sent that city’s numbers skyward.

The fraction of new ADUs relative to total new homes is a useful metric for comparing cities because it normalizes differences in housing market strength, which can have a big effect on the production rate of all types of homes. In other words, it helps isolate the effect of restrictive regulations.

A second way to compare ADU production is to normalize against the number of single-family homes, which approximates the number of sites available for ADUs. Los Angeles’ population is roughly five times Seattle’s, and it has about four times as many single-family houses. On a per-house basis, prior to 2017 Seattle was building from three to five times more ADUs than Los Angeles was. In 2018, however, Los Angeles sprinted so far ahead of Seattle that even on a per-house basis it permitted six times more ADUs.

Seattle is the largest city in the four-county central Puget Sound region, home to about 4.3 million residents. For the region, the fraction of total housing permits that were for ADUs hovered around 1 percent from 2013 to 2016 (see table above). Anemic ADU production is not just a Seattle problem in Washington.

State preemption has its place

If ever there was a compelling argument for enacting state laws to preempt local land use rules, it’s the Los Angeles ADU story. Since the 1980s Los Angeles struggled to reform its ADU policies, and never managed to enact a set of regulations liberal enough to unleash ADU construction.

California’s ADU law didn’t pull any punches: it mandated an extensive and detailed set of rules and limits on requirements, and gave cities a hard deadline with a short timeline by which to comply. Los Angeles missed the deadline, was forced to adopt the state’s rules, and ADUs took off—really took off! As in, by a factor of 30 over what had been typical in prior years. Amazingly, in 2018, ADUs accounted for 1 in 5 construction permits issued for all new homes in Los Angeles.

Lawmakers from Washington and other states, too, please take note!

UPDATE 4/17/19: California legislators are now attempting to push the envelope further with SB 13, which would explicitly ban owner occupancy requirements, eliminate impact fees for ADUs less than 750 square feet, and cap impact fees for larger ADUs at a quarter of the rate applied to single-family homes. The bill must pass out of committee by May 3. Last year California failed to pass SB 831, which would have fully eliminated ADU impact fees, prohibited separate utility connection charges for most ADUs, mandated minor parking reductions, and streamlined permitting. During the session lawmakers nixed the impact fee and utility provisions, but added prohibitions on owner occupancy requirements, lot coverage standards, and inclusion of ADUs in floor area ratio limits.

Data notes

Los Angeles permit data for ADUs and all housing units were generously provided by the Los Angeles Department of City Planning.

Permit data for the Puget Sound Region were generously supplied by Christy Lam with the Puget Sound Regional Council. The data set excludes two cities in the region: Skykomish and South Prairie. Also, for the following cities it includes housing permit data but no separate data for ADUs: Carnation, Milton, North Bend, Tukwila, Yarrow Point, Dupont, Eatonville, Gig Harbor, Pacific, Roy, Ruston, Darrington, Gold Bar, Granite Falls, Index, Mukilteo, and Sultan. These cities account for just 2 percent of typical annual permits in the region, so the missing ADU data should not significantly alter the ADU permit fraction for the region.

Comments are closed.