Oregonians have been pushing for comprehensive climate action for more than a decade. Other states and provinces in North America have forged ahead, attracting clean energy investments, creating local jobs, and cleaning up the air they breathe but Oregonians are still paying price for someone else’s pollution—hospital bills for our kids’ asthma, a faltering seafood industry, wildfires, and more.

With not a moment to spare, Oregon’s elected leaders are united in making carbon pricing legislation a priority for this session. A joint committee spent most of last year holding hearings and drafting a cap-and-invest bill to limit pollution and put proceeds toward clean energy and jobs. House Bill 2020 has seen several public hearings so far this session and legislators are currently working on amendments. We’ll update our analysis once those amendments are released.

Here’s how the current bill stacks up against Sightline’s three big policy questions for any carbon pricing proposal.

- The cap will be pretty good, but not quite strict enough.

- Much of the revenue, sadly, will go for free to utilities and industrial facilities, as well as to the Highway Trust Fund.

- The bill still gets a lot of design details right but includes a few worrying aspects.

How strict will the cap be?

The cap limits how much pollution large polluters can release into the air each year from 2021 through 2050. For the program to be effective at curbing pollution, the cap must decline quickly enough so that pollution goes down faster, and also covers most of the pollutants and polluters in the state.

As it stands, Oregon’s cap is pretty darn good… but could be better. Maybe the amendments, expected any day now, will tighten it.

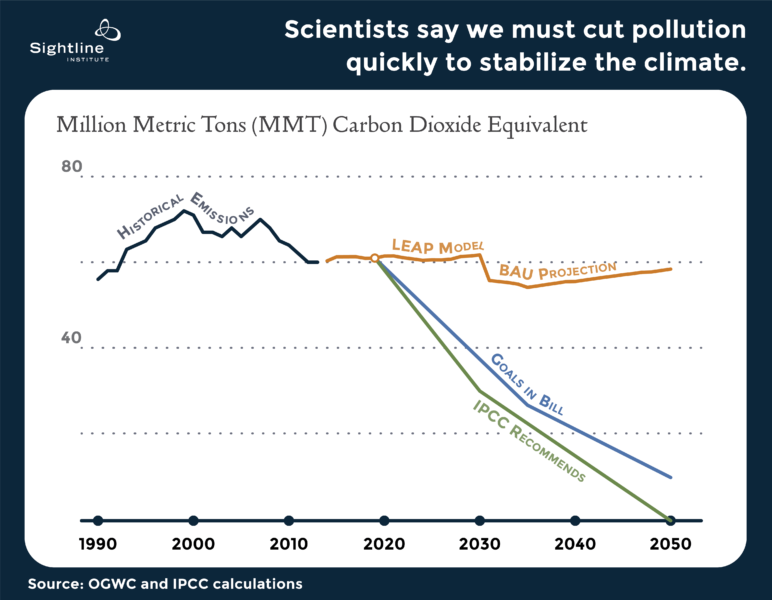

Oregon’s cap doesn’t go down far or fast enough

On the upside: Oregon leaders briefly flirted with the idea of eliminating a 2035 goal so the cap would decline more slowly but they ultimately kept both a 2035 goal (cut pollution to at least 45 percent below 1990 levels) and a 2050 goal (slash pollution to at least 80 percent below 1990 levels).

This is a respectable rate of decline and if Oregon had enacted an enforceable limit on pollution ten years ago, it might have been a sufficient contribution toward stabilizing the climate. But unfortunately, each passing year adds more pollution to the atmosphere, which brings us to the downside: The next decade is critical to climate stability. As environmental justice advocates in Oregon have pointed out, a stricter cap—a 2025 goal of 25 percent cuts, a 2035 goal of 55 percent cuts, and a 2050 goal of net zero pollution, for example—would put Oregon more in line with where scientists say we need to be. International scientists now recommend cutting pollution 45 percent below 2010 levels by 2030, and to net zero emissions by 2050.

Oregon’s cap covers all major pollutants

Although advocates sometimes talk about limiting “carbon,” a well-designed program needs to cover more than just carbon dioxide. Happily, Oregon’s cap covers all seven major pollutants: carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O), hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), perfluorocarbons (PFCs), sulfur hexafluoride (SF6) and nitrogen trifluoride (NF3).

Oregon’s cap covers major polluters

Oregon’s cap would also cover most polluters, including electricity, natural gas, transportation, and large industrial sources. Together, these add up to about 85 percent of all climate pollution in the state. The cap does not cover waste disposal sites, agricultural sources, airplanes, boats, railroads, and it exempts cogeneration facilities (plants that produce both electricity and heat) operated by a public university or the state.

What would revenue be used for?

A cap-and-invest program uses permits to enforce limits on pollution. A permit, also called an allowance, lets the holder emit one ton of pollution. The number of allowances created is equal to the cap (if the cap is set at 100 tons annually, there are 100 allowances available per year). Polluters must submit an allowance for every ton they pollute or face steep monetary penalties. The state can choose to auction off the allowances, which sets a market price for pollution and generates revenue. The state may also choose to give the allowances to polluters for free, in which case the polluters get the full value of the allowance and the state gets no revenue.

Oregon’s current bill chooses to give a lot of allowances away for free, and almost all of what remains gets siphoned into the Highway Trust Fund. Hopefully, the amendments will give less away to polluters and keep more for investing in Oregon.

Unfortunately, Oregon’s bill gives lots of free handouts.

The Oregon bill would give electric utilities all their allowances for free through 2030, and natural gas utilities might get the same. Certain industrial plants would get all their allowances free in the first year. This could have two negative outcomes: first, there isn’t any revenue coming in from these sectors to invest in clean energy and jobs. Second, it could undermine the market and lead to distorted prices.

The Oregon bill could avoid the pitfalls of totally free allowances by taking the minimal step of forcing utilities to buy some of their allowances in a consignment auction. Other programs have given utilities all or most of their allowances for free, but then forced them to sell and buy back those allowances in a “consignment” auction—meaning the allowances belong to the utilities, but they temporarily consign them to auction and then buy them back. Experience shows that even a small “consignment” auction can ensure a more accurate price. Giving utilities their allowances for free lets them ignore their pollution, but forcing them to bid in a consignment auction compels them to grapple with the question of how much they would be willing to pay for allowances. In other words, it forces them to take the cost of pollution seriously.

Some important investments

After all those free allowances, there might be precious little revenue from the program (outside the Highway Trust Fund, which is explained below), especially in the early years. We’re talking less than $80 million per year for the whole state. That’s on the same order of magnitude as what the city of Portland alone will raise for investments from its Clean Energy Fund. The meager revenue that remains for the state will go into the Climate Investments Fund to support important things like energy efficiency, renewable energy, land use planning, natural and working lands, reducing air pollution, and improving the resiliency of Oregon’s fish and wildlife ecosystems.

Within the Climate Investments Fund, 10 percent of the money must benefit Indian Tribes, and a yet-to-be-determined portion must go to the Just Transition Fund to support job creation, job training, and support for workers adversely affected by climate change or climate change policies.

And the Highway Trust Fund

The transportation sector is the biggest source of pollution and therefore the biggest source of revenue in Oregon. At the start, sellers of dirty transportation fuels will collectively pay around $400 million per year for allowances and the amount will increase as the cap tightens, allowances become scarcer, and their price goes up. However, the state’s Constitution puts limits on how the state can use that money. Namely, it must spend it on “the construction, reconstruction, improvement, repair, maintenance, operation and use of public highways, roads, streets and roadside rest areas.” The bill creates a Transportation Decarbonization Investments Account within the Highway Trust Fund in an attempt to put the money toward purposes that both meet constitutional requirements and also help with the state’s climate goals.

Here’s the thing: there are oodles of great opportunities for a true Transportation Decarbonization Investment Account. To name a few:

- Enhancing operations so that more people can conveniently use transit to get where they need to go

- Investing in safe streets so that people who walk or bike can choose to do so without fear

- Investing in charging infrastructure for electric vehicles, especially for fleets that serve many people rather than private vehicles that serve just one owner

But the current restrictions will cut out many of those important investments.

To make the most of the Oregon Clean Energy Jobs Bill, Oregon needs to revise its Constitution to allow investments in clean transportation options.

Short of that, Oregon could use the transportation sector money to create a “Climate Kicker,” instead of letting all the money bleed into new mega-highway projects. By refunding all of the transportation money back to drivers in the form of a “Climate Kicker,” Oregon could give a financial bump to Oregon drivers. And it could avoid digging the climate hole deeper by providing funding that might encourage driving by widening highways.

Does the policy get the design details right?

The devil is in the details. Oregon’s bill gets a lot of design details right but includes a few worrying aspects. In particular, Oregon does not appear to have learned from other program’s experience and set up a way to deal with oversupply. But it has set a hard price floor, which ensures polluters will pay at least that amount for allowances.

Adjusting the cap in case of oversupply

Other pollution caps—including the northeastern states’ RGGI program, the European Union’s, and California’s—all set the bar too low at the outset or found their pollution limits were too high as the program went on. In other words, polluters were able to reduce pollution more quickly than expected, so the cap no longer kept the pressure on to continue cutting. Oregon should learn from the programs that came before it and include a mechanism for adjusting the cap. One simple mechanism would be to track the number of unused allowances, and, if the pool of unused allowances gets too high, automatically divert allowances from the program into a price reserve. That price reserve could then be used to create a softer price ceiling that doesn’t violate the cap (see below).

Banking and borrowing

The Oregon bill gets this right, encouraging early action because every year counts when it comes to stabilizing the planet. It allows banking but not borrowing. This encourages polluters to:

- Cut emissions as soon as possible because they can always bank extra allowances for a future date

- Not to procrastinate because they can’t borrow against hoped-for future reductions to make up for polluting more today.

However, banking needs to be paired with a mechanism to adjust the cap, as described above, in case too many allowances go into the bank.

Price floor, ceiling, and reserve

As we at Sightline have said before, a carbon tax gives certainty about the price but leaves questions about how much it can reduce pollution. A cap gives certainty about pollution reduction but also leaves room for price volatility. Oregon’s bill sets a hard floor that prices can’t dip below (and guarantees that it’ll get more expensive for polluters) and sets a ceiling that triggers unlimited allowances to bring prices back down.

Unfortunately, that hard price ceiling is like a get-out-of-jail-free card. It flouts the whole idea of putting a hard limit on pollution, which is the entire point of the cap. Other programs have used a soft price ceiling that releases allowances from a reserve pot to moderate the price without breaking the cap.

Linkage

Oregon is a relatively small market. It would benefit from joining the broader North American market through more market flexibility, less market volatility, and lower administrative costs. The bill seems set up to link, but its cap doesn’t exactly track California’s goal of 40 percent below 1990 levels by 2030. It might run into problems convincing California and Quebec that its cap is as strict as theirs and therefore qualified to link. It would be a disappointment for the Beaver State to come this far just to go it alone.

Offsets

Offsets are pollution reductions outside the cap that a capped entity can purchase and use in place of an allowance. For example, an industrial facility that is covered by the cap could purchase an offset that funds reductions in emissions from agricultural operations that aren’t covered by the cap. Advocates for offsets argue that they can spur innovation and reductions in sectors that are harder to regulate, such as forestry. Opponents of offsets worry that they let polluters off the hook, and in particular that they allow polluters to keep spewing into already-bad air quality areas while purchasing offsets elsewhere. Oregon’s bill attempts to strike a balance, by limiting offsets to no more than 8 percent of an entity’s compliance obligations (like California and Quebec do) and also allowing additional restrictions on offsets in bad air quality areas.

Oregon’s Chance to Act

Ten American states and three Canadian provinces are already leading the way with their own successful pollution pricing programs, which are attracting clean energy investments, creating local jobs, and cleaning up the air they breathe. Meanwhile, Oregonians are still paying the prices of someone else’s pollution through hospital bills for our kids’ asthma, a faltering seafood industry, wildfires, and more. In the face of a deafening lack of climate action at the federal level, Oregon can join the burgeoning ranks of climate realists and chart a healthier, safer path forward by finalizing the 2019 Clean Energy Jobs Bill. Oregon legislators have until the end of June to pass this bill into law.

Comments are closed.