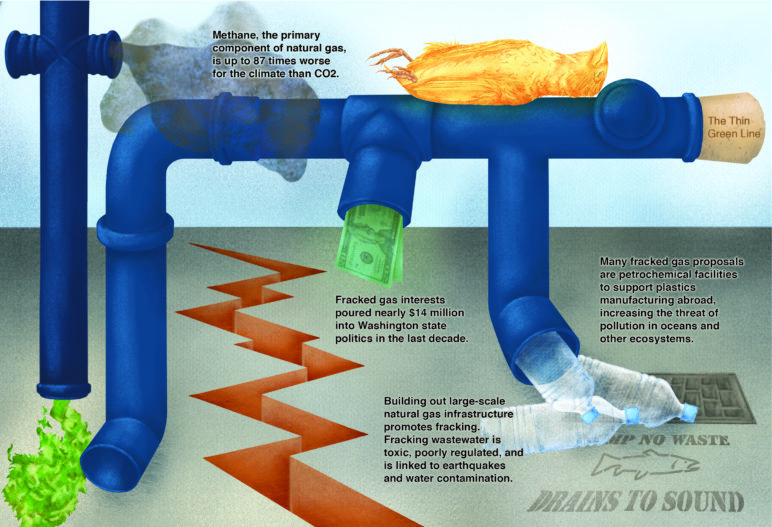

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]The fossil fuel industry purports that natural gas is “clean,” but that claim fails to account for climate-damaging methane leaks along the supply chain. Poor external reporting requirements mean gas companies don’t have to share how much fugitive methane escapes into the atmosphere each year. With no one to compel more data-sharing from the industry, it can convince policymakers and the public that any uncertainty in independent research is enough reason to discredit the questions themselves.

Despite uncertainty outside the industry about how much methane is leaking, the available data make a few things clear: natural gas is most likely a climate disaster dressed as a solution, and better accounting of methane releases could help us avoid the tremendous mistake of investing in large-scale fracked gas infrastructure that will compound our climate crisis.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

This is part of a trilogy of articles to provide depth and context to methane leaks. Read the other pieces in this series:

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_btn title=”Part 1″ color=”primary” size=”lg” align=”center” button_block=”true” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.sightline.org%2F2019%2F02%2F12%2Fcalling-natural-gas-a-bridge-fuel-is-alarmingly-deceptive%2F||target:%20_blank|”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_btn title=”Part 2″ color=”primary” size=”lg” align=”center” button_block=”true” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.sightline.org%2F2019%2F02%2F12%2Fmethane-climate-change-co2-on-steroids%2F||target:%20_blank|”][/vc_column][vc_column][vc_column_text] [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]The Union of Concerned Scientists estimates that annual US “fugitive” methane emissions—methane unintentionally released into the atmosphere—from fracked gas infrastructure are equivalent to the heat-trapping pollution from between 35 and 314 coal-fired power plants. The range is so broad because scientists have to draw conclusions from partial data. There are relatively few rules (and weak, inconsistent ones at that) to govern the industry’s reporting of fugitive emissions, so researchers are still uncertain about exactly how much methane is leaking into the atmosphere from fossil fuel infrastructure such as pipelines, extraction sites, and processing equipment.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]The Union of Concerned Scientists estimates that annual US “fugitive” methane emissions—methane unintentionally released into the atmosphere—from fracked gas infrastructure are equivalent to the heat-trapping pollution from between 35 and 314 coal-fired power plants. The range is so broad because scientists have to draw conclusions from partial data. There are relatively few rules (and weak, inconsistent ones at that) to govern the industry’s reporting of fugitive emissions, so researchers are still uncertain about exactly how much methane is leaking into the atmosphere from fossil fuel infrastructure such as pipelines, extraction sites, and processing equipment.

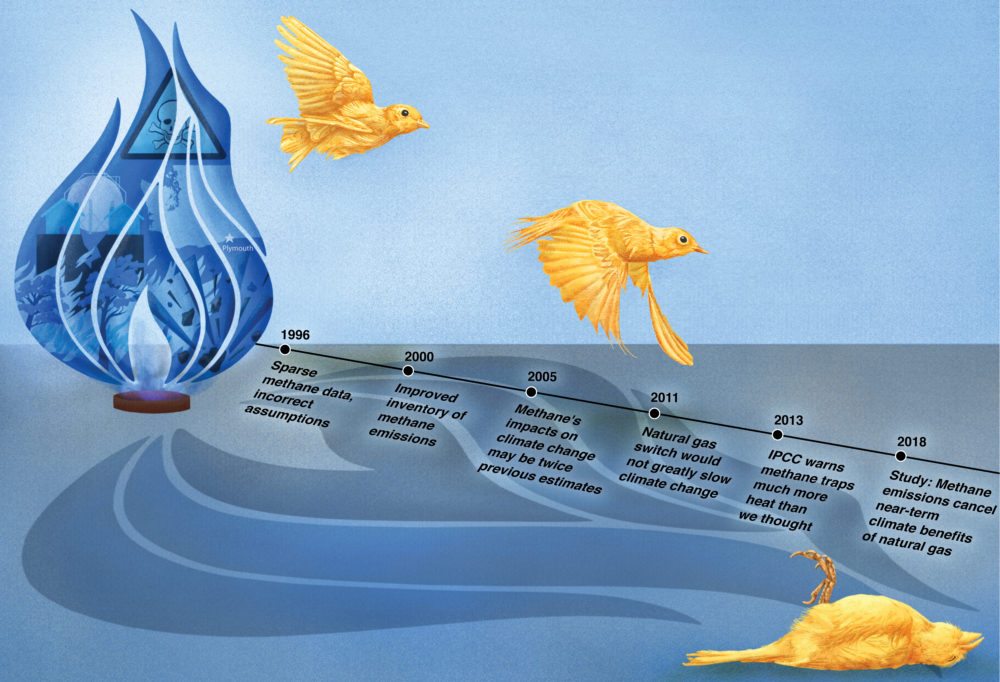

In our previous articles in this series, we discussed the global warming potential (GWP) of methane.

This article will take a look at how much methane is leaking into the atmosphere—what we know and what we yet need to find out. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Despite debate over source, there’s no doubt US methane emissions are increasing

Atmospheric concentrations of methane are much higher than pre-industrial levels. In fact, they have more than doubled over the last two centuries largely due to human activities and man-made emissions, which account for 50 to 65 percent of the total amount of methane that enters the atmosphere each year.

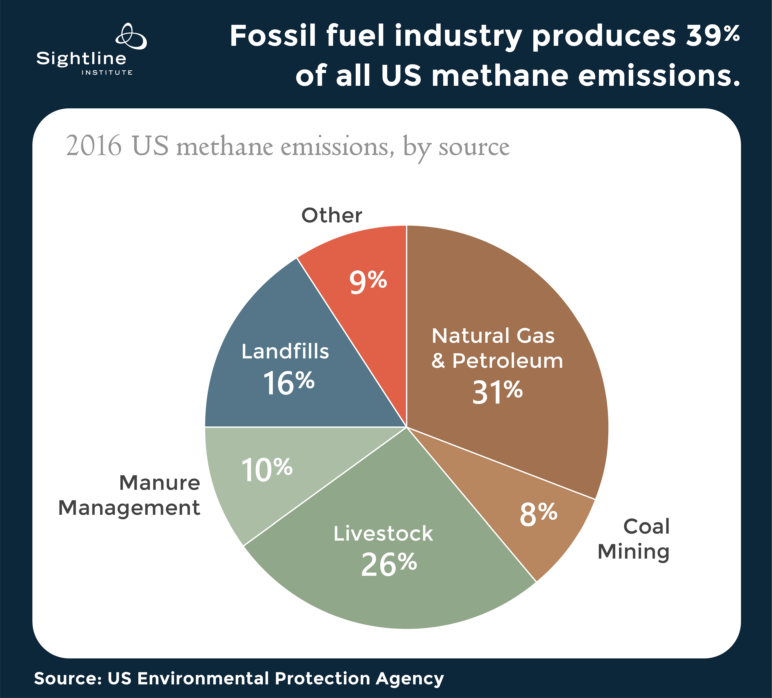

In the United States, methane emissions have increased rapidly in the 21st century, perhaps by more than 30 percent. The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimates that in 2016, the principal sources of methane released by human activities in the United States were: oil and gas production and distribution (31 percent), livestock (26 percent), landfills (16 percent), manure management (10 percent), and coal mining (8 percent). All other sources accounted for 9 percent of US methane emissions. The combined methane emissions of the fossil fuel industry (oil, gas, and coal) made up 39 percent of the US total, while the combined methane emissions of livestock (including manure) accounted for 36 percent.

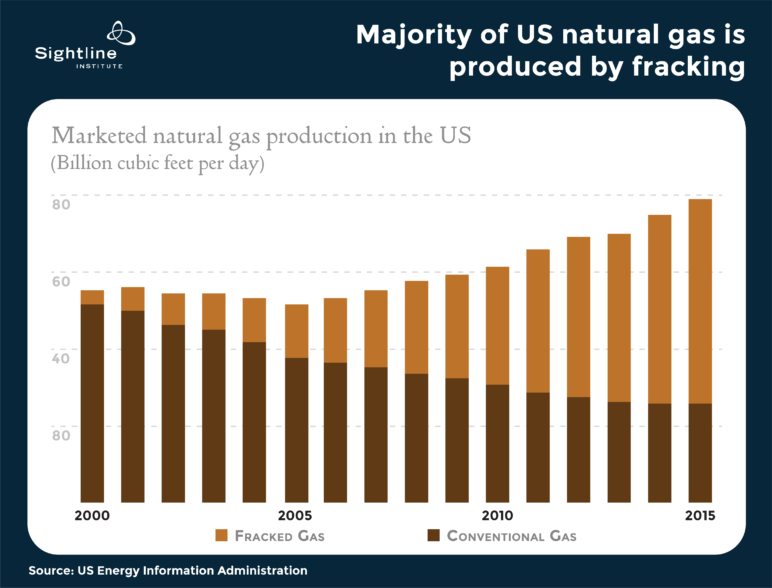

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]The fracked gas sector is particularly worth exploring because it ushered in the rapid increase in US natural gas production. Although agricultural practices account for more than one-third of all US methane emissions and are a serious concern for climate change, the fossil fuel industry represents the largest share. Gas production from fracking more than doubled between 2005 and 2015, going from about a third of US gas production to nearly 70 percent. (Gas production from non-fracked sources actually declined during this period.)

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]The fracked gas sector is particularly worth exploring because it ushered in the rapid increase in US natural gas production. Although agricultural practices account for more than one-third of all US methane emissions and are a serious concern for climate change, the fossil fuel industry represents the largest share. Gas production from fracking more than doubled between 2005 and 2015, going from about a third of US gas production to nearly 70 percent. (Gas production from non-fracked sources actually declined during this period.)

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Because natural gas is composed primarily of methane, it would be easy to assume that fracking is the culprit behind rising methane emissions. That may be true in part, yet correlation is not causation. It is difficult for researchers to unambiguously identify the source of recent increases in methane emissions due to data limitations. Instead of providing clarity, studies that attempt to quantify methane emissions can lead to greater confusion. That’s because scientists use two very different methods of analysis to attempt to quantify methane leaks from the oil and gas industry: top-down studies and bottom-up studies. The method of analysis can have a big impact on a study’s outcome, leading to competing claims about how harmful the fracked gas industry is to the climate.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Because natural gas is composed primarily of methane, it would be easy to assume that fracking is the culprit behind rising methane emissions. That may be true in part, yet correlation is not causation. It is difficult for researchers to unambiguously identify the source of recent increases in methane emissions due to data limitations. Instead of providing clarity, studies that attempt to quantify methane emissions can lead to greater confusion. That’s because scientists use two very different methods of analysis to attempt to quantify methane leaks from the oil and gas industry: top-down studies and bottom-up studies. The method of analysis can have a big impact on a study’s outcome, leading to competing claims about how harmful the fracked gas industry is to the climate.

Bottom-up studies take measurements at select fracked gas facilities and extrapolate the results to the rest of the industry. Researchers conducting bottom-up studies measure emissions by sampling methane leaks directly from several specific sources in a region, then essentially multiplying the results by the number of similar facilities in that region. The top-down approach measures methane concentrations in the atmosphere and then tries to identify the likely emissions sources by estimating or modeling how the methane migrates once it’s in the atmosphere. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Both methods have weaknesses. It’s difficult for top-down studies to unambiguously identify the source of the methane detected in the atmosphere—these studies can’t definitively say whether methane is from a specific fracking site or landfill or manure lagoon. Bottom-up studies notoriously lack enough measurements to capture the range in leakage from one facility to the next, often taking samples only at lowest-emitting facilities, resulting in an underestimation of methane escape. (See 1, 2, 3)

Top-down studies at least capture a more accurate picture of the quantity of methane released into the atmosphere in a given region. By contrast, bottom-up studies on local and regional scales consistently underestimate emissions. The data in bottom-up studies are usually from facilities that volunteered to participate in a study, and they aren’t representative of the range in leakage at different facilities. Many bottom-up studies do not disclose their sampling methods and some experts criticize this method for cherry-picking measurements from low-emitting pieces of infrastructure.

The fracked gas industry is plagued by “super emitter” facilities that are responsible for a disproportionately large share of regional emissions.

Sampling that accurately represents the full range of facilities is critical to methane accounting. The fracked gas industry is plagued by “super emitter” facilities that are responsible for a disproportionately large share of regional emissions. Bottom-up studies that exclude super emitters could grossly underestimate methane emissions. Many scientists recommend verifying bottom-up methane studies with top-down (or atmospheric) measurements. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Since 1990, the EPA has published an annual report that tracks US emissions by greenhouse gas, by source, and by economic sector to try to account for climate-changing emissions from all man-made US sources. For the first 20 years of this greenhouse gas inventory (GHGI), the methane data were based on bottom-up measurements from facilities that the industry volunteered for leakage measurement. There is now widespread agreement, however, that EPA’s bottom-up greenhouse gas inventory consistently underestimated US methane emissions by a factor of 1.5 (50 percent) or more. (See 1, 2, for example.) In the South Central United States, where there are a large number of oil and gas fracking basins, the inventory appears to underestimate methane emissions by nearly a factor of five. (Note that because the source of methane emissions are often difficult to identify, the EPA’s persistent underestimation could also apply to methane from sources such as livestock and wetlands.)

The EPA’s bottom-up greenhouse gas inventory consistently underestimated US methane emissions by a factor of 1.5 (50 percent) or more.

Policymakers should understand that emissions inventories provide estimates. Before policymakers permit further construction of fracked gas facilities, like liquefied natural gas (LNG) export terminals and new pipelines, they should require much better proof that these are cleaner choices. That includes better industry reporting, studies using random sampling techniques, and verification of bottom-up studies with top-down atmospheric methane observations. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

A life cycle analysis: fairly evaluating fracked gas projects

The standard review process for gas-based projects is failing to capture the true sources of harm from fracked gas. To accurately compare gas projects to other energy alternatives, officials should conduct a lifecycle analysis to capture a more complete picture of greenhouse gas emissions. A life cycle analysis is a calculation that takes greenhouse gas emissions throughout the supply chain into account. When applied to fracked gas, life cycle analyses factor in emissions from “upstream” processing (things like building and operating a gas extraction well, processing the gas to remove impurities, and shipping it via pipeline), processes at a fracked gas or LNG facility, shipping emissions, and combustion. This comprehensive review is important because methane is leaked or intentionally released at each of these stages in the fracked gas life cycle.

To understand why a life cycle analysis is critical to evaluating fracked gas projects, we can look at the example of an LNG export facility. A 2015 study on LNG exports found that typical emissions from processes at the facility and shipping account for less than 11 percent of the total life cycle emissions—yet these are often the only emissions that project reviewers are taking into account. In fact, sometimes even the shipping emissions are also omitted from review.

So what about the 89 percent of emissions that are being ignored? The largest share of LNG project emissions come “downstream” from the end-use combustion—the burning of the fuel at its destination. The second-largest release of greenhouse gases comes from “upstream” emissions sources, such as leaks along the transmission infrastructure that moves the gas from wellhead to facility. Using an average assumption about leakage rates, the study estimated that upstream methane emissions are nearly five times the emissions produced at the LNG facility itself. A life cycle analysis is designed to provide a more complete picture of a project’s climate impact by measuring both upstream and downstream emissions.

Life cycle analyses show that focusing on a narrow set of emissions at a gas facility is blinkered accounting. It leaves far more significant emissions in a regulatory blind spot than it counts, thereby grossly understating the actual impacts of fracked gas on climate change.  [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]It’s unlikely that end-use combustion will be included in the environmental assessment of a facility, especially for an export facility where the fuel burning occurs in another country. But there is still some reason for optimism. Northwest regulators are beginning to recognize that upstream methane leakage is an important factor to consider. In 2018, for example, environmental assessments of fracked gas projects in Kalama and Tacoma, Washington, were rejected or sent back for supplemental review because they did not include important life cycle emissions components. Yet without a clear and broad understanding of what modern science says about fracked gas, uncertainty may continue to pay large dividends for the fossil fuel industry.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]It’s unlikely that end-use combustion will be included in the environmental assessment of a facility, especially for an export facility where the fuel burning occurs in another country. But there is still some reason for optimism. Northwest regulators are beginning to recognize that upstream methane leakage is an important factor to consider. In 2018, for example, environmental assessments of fracked gas projects in Kalama and Tacoma, Washington, were rejected or sent back for supplemental review because they did not include important life cycle emissions components. Yet without a clear and broad understanding of what modern science says about fracked gas, uncertainty may continue to pay large dividends for the fossil fuel industry.

Thanks to Adrian Down and Marcia Baker, who contributed research to this series.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

This is part of a trilogy of articles to provide depth and context to methane leaks. Read the other pieces in this series:

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_btn title=”Part 1″ color=”primary” size=”lg” align=”center” button_block=”true” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.sightline.org%2F2019%2F02%2F12%2Fcalling-natural-gas-a-bridge-fuel-is-alarmingly-deceptive%2F||target:%20_blank|”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/2″][vc_btn title=”Part 2″ color=”primary” size=”lg” align=”center” button_block=”true” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.sightline.org%2F2019%2F02%2F12%2Fmethane-climate-change-co2-on-steroids%2F||target:%20_blank|”][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Comments are closed.