[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Methane gas, commonly referred to as “natural gas,” is the fossil fuel with the most positive image. Natural gas is marketed as not just cleaner than other fossil fuels, but as “clean”—a demonstrably false descriptor with an endless number of caveats. Oil and gas companies promote gas subsidiaries by prominently featuring the word “clean” in the company’s name or marketing and suggest we pair natural gas with renewable energy as a solution to our greenhouse gas problems. This dubious pairing has found its way into decarbonization policy at both the state and federal level. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

This is part of a trilogy of articles to provide depth and context to methane leaks. Read the other pieces in this series:

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_btn title=”Part 2″ color=”primary” align=”center” button_block=”true” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.sightline.org%2F2019%2F02%2F12%2Fmethane-climate-change-co2-on-steroids%2F||target:%20_blank|”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_btn title=”Part 3″ color=”primary” align=”center” button_block=”true” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.sightline.org%2F2019%2F02%2F12%2Fstudy-methane-life-cycle-critical-pacific-northwest%2F||target:%20_blank|”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][vc_column][vc_column_text] [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]The oil and gas industry’s greenwashing campaign for methane gas began decades ago when it rebranded the product as “natural gas”—a hugely successful strategy. Studies show that the average American believes natural gas to be a clean fuel that does little harm from a climate or pollution perspective. Natural gas proponents point out that gas produces less carbon emissions than coal or oil at the point of combustion. That’s an accurate statement. At the point of combustion, natural gas has a smaller carbon footprint than other fossil fuels, and it can yield as much energy as coal with roughly half the carbon emissions. The reduction of carbon dioxide—the most prevalent greenhouse gas in the atmosphere—is a goal around which most climate policy is focused. Measured per unit of energy produced, natural gas combustion also emits fewer air pollutants including carbon dioxide, small particulate matter, nitrous oxide, and sulfur dioxide. Some of these pollutants, like diesel particulate matter, pose serious health risks. [/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]But the point of combustion is just one stage in the life-cycle of natural gas. There’s a reason the industry deliberately ignores the remainder of emissions produced by natural gas: there is strong evidence that when the full life cycle is taken into account, natural gas can produce the same amount or more greenhouse gas emissions as other fossil fuels. The problem with gas—and it’s a big one—is that it contributes to global warming before ever reaching the point of combustion. Transporting and processing natural gas leaks methane, a much more potent greenhouse gas, directly into the atmosphere. Methane makes up 85 to 95 percent of the natural gas customers receive, and it is 34 to 87 times more potent than carbon dioxide when it comes to trapping heat in the atmosphere.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]The oil and gas industry’s greenwashing campaign for methane gas began decades ago when it rebranded the product as “natural gas”—a hugely successful strategy. Studies show that the average American believes natural gas to be a clean fuel that does little harm from a climate or pollution perspective. Natural gas proponents point out that gas produces less carbon emissions than coal or oil at the point of combustion. That’s an accurate statement. At the point of combustion, natural gas has a smaller carbon footprint than other fossil fuels, and it can yield as much energy as coal with roughly half the carbon emissions. The reduction of carbon dioxide—the most prevalent greenhouse gas in the atmosphere—is a goal around which most climate policy is focused. Measured per unit of energy produced, natural gas combustion also emits fewer air pollutants including carbon dioxide, small particulate matter, nitrous oxide, and sulfur dioxide. Some of these pollutants, like diesel particulate matter, pose serious health risks. [/vc_column_text][vc_column_text]But the point of combustion is just one stage in the life-cycle of natural gas. There’s a reason the industry deliberately ignores the remainder of emissions produced by natural gas: there is strong evidence that when the full life cycle is taken into account, natural gas can produce the same amount or more greenhouse gas emissions as other fossil fuels. The problem with gas—and it’s a big one—is that it contributes to global warming before ever reaching the point of combustion. Transporting and processing natural gas leaks methane, a much more potent greenhouse gas, directly into the atmosphere. Methane makes up 85 to 95 percent of the natural gas customers receive, and it is 34 to 87 times more potent than carbon dioxide when it comes to trapping heat in the atmosphere.

“When the full life cycle is taken into account, natural gas can produce the same amount or more greenhouse gas emissions as other fossil fuels.”

From the drilling site to the consumer, methane easily escapes into the atmosphere at various points along the supply chain. The release of methane gas offsets the climate benefits at the point of combustion. Methane leaks from fossil fuel infrastructure take two forms: fugitive emissions and venting. “Fugitive emissions” are unintentional leaks from gas distribution infrastructure such as drilling sites, pipelines, and compressor stations. Aging natural gas infrastructure in the US is spewing untold amounts of methane directly into the atmosphere on a daily basis. “Venting” is the intentional release of methane, which happens all along the supply chain—from drilling sites to gas processing and storage sites such as LNG facilities.1[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]All told, drillers on federal lands alone released enough gas into the atmosphere between 2009 and 2014 to power 5.1 million homes for a full year. Several high profile incidents, including the disastrous 2016 Aliso Canyon gas leak in California, are merely the tip of a proverbial iceberg containing millions of ongoing leaks and intentional methane releases. Over the past decade, widespread observations of high methane emissions have not only called into question whether we are getting the facts right on natural gas but strongly suggested that we are not.

Methane leakage is an oft-ignored pathway to global warming and the nexus of debate over the true climate impacts of gas. Understanding and engaging in this debate is vital before we expand natural gas infrastructure in the Pacific Northwest. Focusing only on the point of combustion produces confusion and misinformation about natural gas’s ability to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, or serve as a “bridge fuel” to renewable sources of energy.2 Then there’s the confusing terminology, unsettled and emerging science, and deliberate misrepresentations by the gas industry. The result is an alarming lack of awareness when it comes to the true climate implications of natural gas. People who in good faith believe that natural gas is a cleaner alternative have been deceived for decades.

It’s time for a reality check: When researchers examine the full impact of natural gas, many conclude that it is not substantially better for the climate than coal. In fact, under some circumstances, it may even be worse.

The purpose of this series is to demystify the “natural” gas debate.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row css=”.vc_custom_1549412017115{padding-top: 0px !important;padding-right: 3px !important;padding-bottom: 0px !important;padding-left: 3px !important;}”][vc_column][vc_column_text]

- Methane traps more heat per pound than carbon dioxide but has a shorter atmospheric lifespan. Policy decisions should look at impacts over multiple time frames.

- The climate benefits of switching to natural gas vary depending on the fuel it is replacing, and it has a break-even point with any “dirtier” fuel. Methane leakage rates must be kept low to avoid breaking even or to justify the significant investments of infrastructure conversion.

- US methane emissions are increasing just as natural gas production is increasing. While there is still debate over the fossil fuel industry’s precise contribution to the increase, we have enough information to take action. Indeed, taking action is the only way we’ll clarify the debate.

- There is widespread agreement that we are underestimating methane emissions and need to strengthen our data through better industry oversight.

- The supposed benefits only consider emissions reductions at the point of combustion, omitting the full picture of natural gas’ greenhouse impact.

These five key facts should inform Northwest policy decisions about natural facilities claiming to be “clean.”

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Why you should care about the natural gas problem

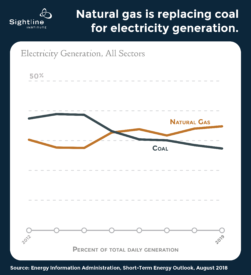

The stakes could hardly be higher. Nationwide in the United States, natural gas extraction and burning are increasing dramatically. The US fracking boom has produced surplus gas supplies and lowered prices. Gas-fired power plants produced 34 percent of US electricity in 2016, up from 22 percent in 2007. In fact, 2016 marked the first year that natural gas was the leading fuel source for US power generation, and it is expected to maintain the largest share of the electricity mix through at least 2040.

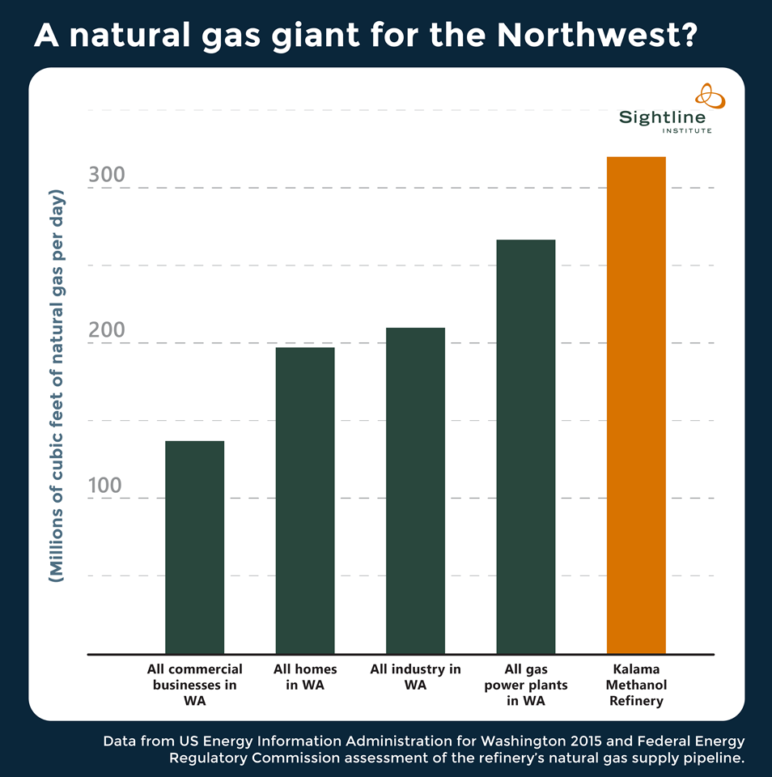

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]In regions like the Pacific Northwest, a range of gas export proposals would further ramp-up fracking, gas consumption, and methane leakage. Just one of these projects, a gas-to-methanol refinery slated for development at Kalama, Washington, would consume more gas than the amount burned by every gas-fired power plant in the state.

The Kalama project, while very large, is not unique. A companion methanol proposal near Clatskanie, Oregon, is just as big. Fossil fuel companies around the Northwest are aiming to build new, large-scale, gas-consuming infrastructure. Over the last few years the Northwest has been confronted with new gas development projects that would consume roughly two billion cubic feet per day. This staggering figure exceeds the total current usage of Idaho, Oregon, and Washington combined. Two such projects are liquefied natural gas (LNG) facilities in Tacoma, Washington, and Coos Bay, Oregon. Meanwhile, the Canadian government has granted export licenses for more than a dozen LNG export projects along the British Columbia coast.

The backers of these projects have marketed their gas expansion plans as environmentally beneficial. The claims are often dubious. While natural gas could have some benefits—replacing existing coal-fired power plants, for example—the rapid expansion of natural gas infrastructure for every other imaginable use will lock the region into the fuel’s detriments. Modern science indicates that if natural gas can still be used as a bridge fuel, and that’s a big “if,” it’s a bridge that must be traversed with a caution the gas industry has proved unwilling or unable to practice. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

High Momentum, High Risk

In the 1970s, the world experienced an energy crisis. Natural gas hit a market peak in the US, and this decade saw the birth of the concept that natural gas could be used as a “bridge fuel” between fossil fuels and renewable energy. Of the three major fossil fuels, methane has the lowest amount of carbon per unit of energy. The bridge fuel concept did not catch on until decades later but it has more momentum than ever, just when both the natural gas industry and our knowledge of its effect on the environment have drastically changed. Now that we are 40 years past the introduction of the “bridge fuel” concept and need to take urgent action on climate change, many scientists warn that we have passed the timeframe in which natural gas could be used as a bridge without worsening climate change.

That’s not all that’s changed. Up until the last decade, natural gas was derived through conventional extraction—in simplified terms, drillers installed piping systems into underground gas basins and gas readily flowed out. Conventional extraction didn’t put much demand on water resources, especially when compared with other fossil fuels. That made it appealing from both a pollution and water consumption perspective. Today, though, two-thirds (67 percent) of the natural gas produced in the United States comes from a harmful and toxic process known as fracking.

Fracking targets geologic formations that contain fossil fuels that are not so easily extracted, primarily tight sands and organic-rich shales. Companies that engage in fracking inject large quantities of water, sand and chemicals—two billion gallons of chemicals between 2005 and 2013—into a fossil fuel well at high pressure. The pressure fractures the earth inside the gas well, releasing larger quantities of gas or oil.

By 2010, natural gas producers were fracking more than 90 percent of the natural gas wells in the United States. The gas fracking boom led to a surplus gas supply and created a drive for the industry to convince domestic and international customers to buy more gas. In turn, more infrastructure must get built to deliver the surplus gas to customers. The possible result of this build-out makes it likely that states and regions will get locked into reliance on fracked gas for the foreseeable future. This would make fracked gas less of a bridge and more of a destination.

Fracking contributed to a dramatic increase in US natural gas production, multiplying the once less-alarming issues related to natural gas. The fracking boom has produced major environmental risks, including lowered freshwater supply and the generation of millions of gallons of toxic and high-salinity fracking wastewater. Fracking poses a greater risk to air and water quality than conventional extraction, and increased fracked gas production leaks more heat-trapping methane into the atmosphere.

Natural gas has changed and so too should our analysis of it. The perils of fracking and the ongoing expansion of scientific knowledge about methane make it clear that if natural gas is to be used as a bridge fuel, the bridge must be traversed carefully. Unfortunately, Northwest policymakers are not traversing the bridge carefully, but rather rushing across it. In recent years there have been three proposals to turn Washington and Oregon into methanol surrogates for China, to the detriment of three Washington cities and their water resources. The misconceptions around natural gas allowed the methanol project’s backers to sweet talk misinformed officials at multiple levels of state and local government.

The success of decades of greenwashing natural gas—now fracked gas—threatens to put Northwest climate goals at risk.

Thanks to Adrian Down and Marcia Baker, who contributed research to this series.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

This is part of a trilogy of articles to provide depth and context to methane leaks. Read the other pieces in this series:

[/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_btn title=”Part 2″ color=”primary” align=”center” button_block=”true” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.sightline.org%2F2019%2F02%2F12%2Fmethane-climate-change-co2-on-steroids%2F||target:%20_blank|”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_btn title=”Part 3″ color=”primary” align=”center” button_block=”true” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.sightline.org%2F2019%2F02%2F12%2Fstudy-methane-life-cycle-critical-pacific-northwest%2F||target:%20_blank|”][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_column_text]Footnotes:

1. Venting methane is also common practice at oil wells and coal basins during the process of extraction.↩

2. The “bridge fuel” concept was first floated in the 1970s when the public knew less about the harms of methane. It proposed that we use natural gas as a transitional fuel between carbon-intensive fuels like oil and gas and renewable energy.↩[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Comments are closed.