In Portland and Cascadia’s other growing cities, housing displacement and exclusion seem automatic. They happen without government action. They are the status quo.

Even if Oregon were to pass a dramatically tighter version of the rent stabilization bill it’s now considering, that alone wouldn’t do a thing for tenants who want to move, which of course just about every tenant does at some point. And that’s where allowing more homes comes in: each home added to a growing city prevents a chain of exclusions from rippling across the region by giving one more household a place to live.

But that benefit of additional homes spreads across an entire housing market. In some neighborhoods, higher redevelopment rates might involuntarily uproot larger numbers of lower-income tenants from family, friendships and culture.

Last week, Portland planners took a close look at this issue. They released their first detailed analysis of displacement as it relates to the city’s proposed fourplex re-legalization.

It’s a long-awaited document. The advocacy groups Anti-Displacement PDX, East Portland Action Plan and Portland for Everyone, not to mention the city’s own planning commission, have been urging the city to conduct this work for years.

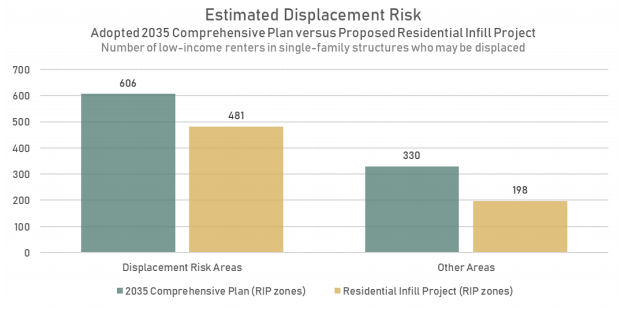

Anti-displacement advocates should generally be heartened by the main finding: A sharp decrease in the number of low-income renters who’d be forced to move from Portland’s lower-density zones due to redevelopment.

But the report is also missing something that some Portlanders seem eager for: A targeted way to reduce low-income renters’ displacement from particularly vulnerable areas. Planners may have valid reasons for omitting this—Anti-Displacement PDX, for example, has opposed geographically specific policies—but if the city ends up looking for neighborhood-level measures anyway, its analysis points toward one useful option.

Fourplex legalization would reduce displacement everywhere except a few critical neighborhoods

Re-legalizing fourplexes, their analysis finds, is good for low-income renters overall:

Exclusive neighborhoods that do not allow for more housing options to absorb a growing and changing population can increase gentrification pressures in other neighborhoods as housing demand spills over and increases housing costs. …

Overall, the proposal is likely to reduce displacement of low-income renters in single-family homes across Portland. This reduction results from allowing more units to be built on one lot, which means fewer lots will be redeveloped across the city. … The proposal will likely significantly reduce the cost of housing for the additional housing types allowed in single-dwelling zones.

The city even puts numbers on this benefit. It calculates that the fourplex legalization would reduce displacement risk of lower-income tenants from detached homes in low-density zones by about 28 percent compared with the status quo. In areas particularly vulnerable to displacement, the net reduction is 21 percent.

It’s worth noting that this reduced rate of demolition-related displacement is due entirely to the lower redevelopment rate in most areas—it doesn’t even capture any indirect anti-displacement benefits of legalizing more homes in the city.

It’s worth noting that this reduced rate of demolition-related displacement is due entirely to the lower redevelopment rate in most areas—it doesn’t even capture any indirect anti-displacement benefits of legalizing more homes in the city.

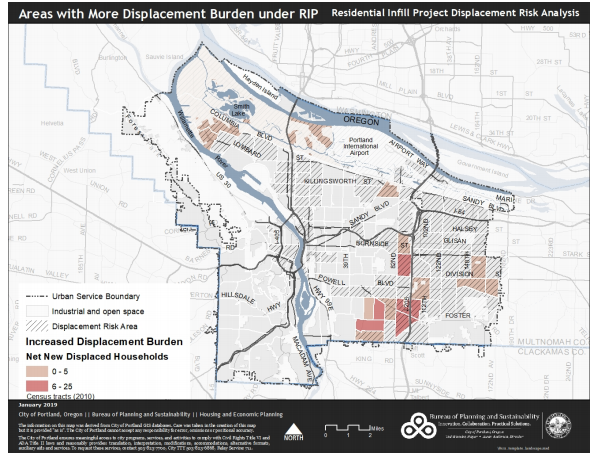

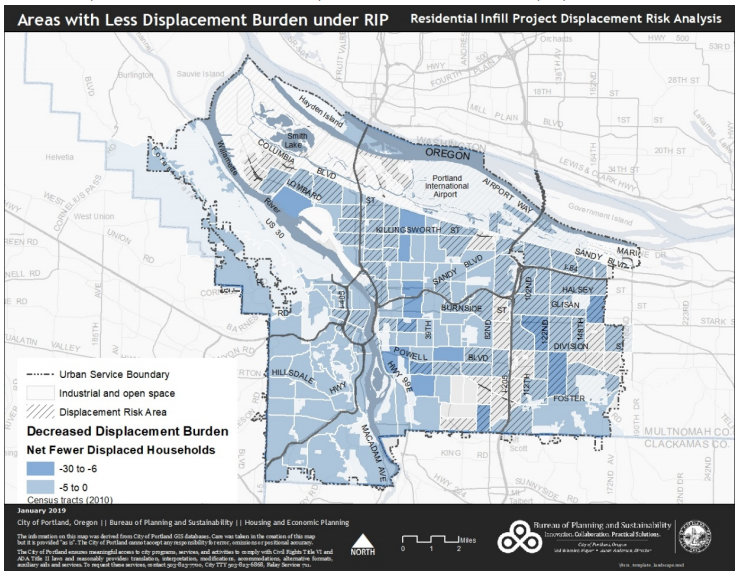

Still, in a few neighborhoods—the borderland between the city’s pre-car and post-car neighborhoods, more or less—the analysis predicts “increases in redevelopment that could lead to the increased displacement of vulnerable households.” Here’s the map:

The city has an option that could, with a pen stroke, sharply reduce demolition in any particular areas it wants to protect

The city’s displacement analysis proposes a handful of mitigation strategies, from renter education to short-term renter assistance to targeted homeownership subsidies. Almost all these ideas are good, and worth raising public money to pay for them.

(One exception: a proposed fee on new homes would end up raising costs for renters and homebuyers. Money for good programs like these should come from the many landowners who aren’t creating homes as well as the handful of landowners who are.)

But none of the ideas presented would be able to target anti-displacement efforts to particular neighborhoods. And for better or worse, that’s a subject many Portlanders are interested in.

So here’s an idea: specifically within particularly vulnerable areas, the city could shrink the allowed size of duplexes, triplexes and quads.

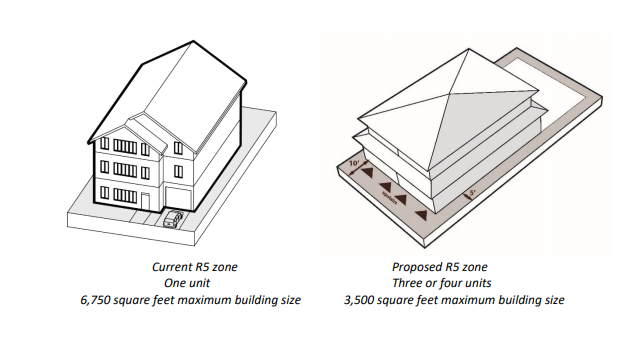

To understand what this means, you need to know how Portland’s unique fourplex legalization proposal works: in an effort to make every demolition count, it penalizes projects that choose to create fewer homes by giving them lower size caps.

For example, a new one-unit building on a standard 5,000 square foot lot in the city’s most common zone could be up to 2,500 square feet, tops. (That’d be down from 6,750 square feet today.) But a duplex could be up to 3,000 square feet (that is, two 1,500 square foot homes) and a triplex or fourplex, up to 3,500 total.

Scaling building sizes this way, it turns out, has a powerful effect on what sort of buildings are likely to get built while also minimizing the number of demolitions per new home. (It’s all based on empirical work that found building size, not unit count, is the main driver of viability for a new building.)

So, essentially, Portland plans to reward buildings that do something good—create more homes—by allowing them to be bigger. If Portland’s zoning reform increases the rate of redevelopment above the status quo in a few neighborhoods, it’s because of this provision. One key finding of a November economic analysis was that adding this provision increases total square footage built in the city’s low-density zones, even though the number of demolitions citywide is essentially unchanged.

So if the city wants to reduce redevelopment rates in those areas, at least until it’s found a way to fund new housing subsidies for them, there’s a fairly simple option: reduce or eliminate this provision for those areas only.

If building size doesn’t scale up with unit count, then the demolition rate won’t scale up, either.

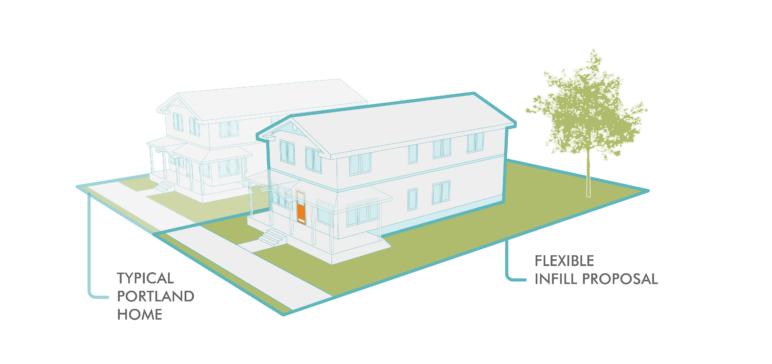

A nice thing about this approach is that even as it reduces redevelopment incentives, it gives new flexibility to homeowners in these areas, who are disproportionately likely to be low-income themselves. If property owners prefer a duplex, triplex or fourplex—for an extended family, for example—they’d still be free to create a small 2,500-square-foot fourplex like this one:

According to the city’s analysis, the building above would be no more likely to cause displacement than the building below, which almost no one is questioning should be legal to build:

Again, allowing buildings to get bigger if they have more homes is basically good—it’s the key reason Portland’s proposal is so effective at reducing displacement citywide. The sooner Portland can get this reform in place, the fewer people will be displaced.

And the city should be very wary of applying the low size cap to too many neighborhoods; a project it prevents in Lents might just trigger a project or two in Centennial instead. A neighborhood-specific size cap isn’t a way to reduce displacement even further, and in fact it might slightly increase total citywide displacement. But it could be one way to distribute the remaining displacements differently.

Bottom line: citywide anti-displacement measures, like the residential infill reform itself, are generally more effective than neighborhood-level ones. But if Portland ends up looking for a relatively straightforward way to offer extra protection to particular neighborhoods, then holding duplexes, triplexes and fourplexes to the same size cap as one-unit buildings is an option worth considering.

Comments are closed.