Middle homes aren’t newfangled. If anything, this kind of legislation effectively re-legalizes home options that are familiar in many Northwest neighborhoods but are no longer allowed.

Legislators in Oregon and Washington are eyeing statewide solutions to keep job centers affordable for middle-income people. Among those being considered in this legislative session are “missing middle” housing proposals aimed to re-legalize a variety of home choices like duplexes, triplexes, and quads in residential city neighborhoods. These kinds of mid-size homes could help curb prices and give moderate-income, working families and small households like seniors or young couples more affordable options.

A bill introduced by Tina Kotek, Oregon’s House of Representatives Speaker, would commit cities with populations of 10,000 and larger to allow a range of home types in more neighborhoods to make sure affordable choices remain available for households of different ages, sizes, and incomes. Lawmakers in Washington State are looking to follow suit, lifting current restrictions that ban all but the most expensive housing in residential neighborhoods across the state.

Middle homes aren’t newfangled. If anything, this kind of legislation effectively re-legalizes home options that are familiar in many Northwest neighborhoods but are no longer allowed. Historically in North American cities, including cities across Washington and Oregon, duplexes, triplexes, and small apartments were built alongside stand-alone houses. Starting in the 1920s, cities began ratcheting up restrictions on what kinds of homes could be built, and by the 1960s, most had banned everything but single-dwelling houses on vast swaths of their land—typically more than half of a city’s residential area. Gradually returning neighborhoods to a healthy mix of homes of all shapes and sizes is a critical part of the affordability solution that so many people in this region need.

Choices about which home types are allowed and which are not shape our communities, especially by determining who can afford to live in them and who cannot. Since 1970, average sizes for new detached houses have soared by 64 percent. When cities choose to stop preventing modest home types and begin again to allow more than one home on a single lot, they can also help reverse the trend to bigger—and pricier—“McMansions.”

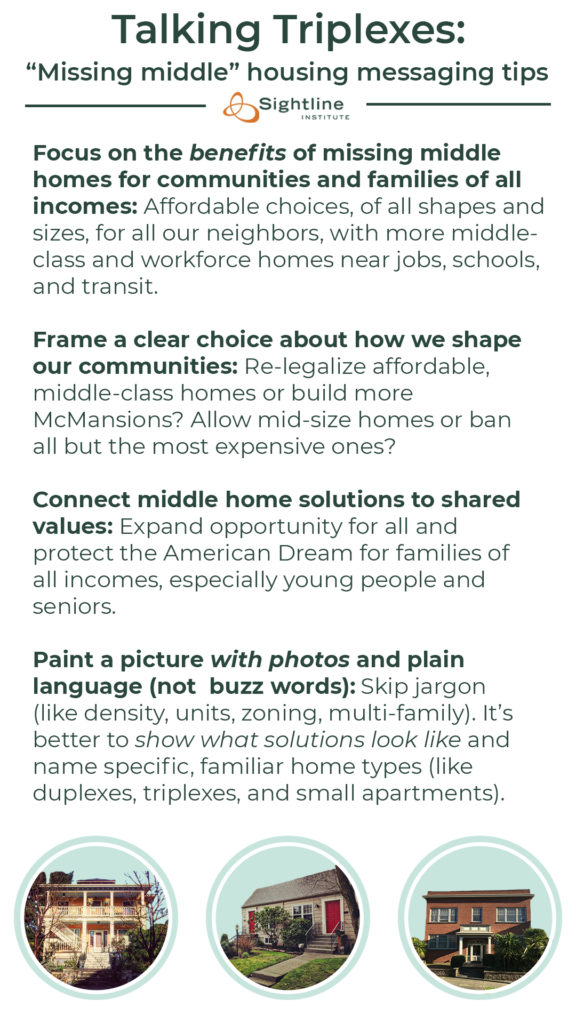

Here are messaging ideas to keep in mind when discussing this kind of middle housing solution:

Focus on the benefits of missing middle home choices for communities and families of all incomes: Re-legalizing middle housing means a range of affordable choices, all shapes and sizes, for all kinds of neighbors. Our communities do better with middle-class and workforce homes near jobs, schools, and transit.

Frame up a clear choice about how we shape our communities: Re-legalize affordable, middle-class homes or more McMansions? Allow mid-size homes or limit communities to all but the most expensive? We either re-legalize homes like duplexes and quads so our communities stay affordable for people of all incomes, or we continue to restrict home choices to the most expensive and exclusive. Allowing a variety of mid-size, modest homes helps protect modest homes—and neighborhoods—from a trend toward bigger and pricier “McMansions” and higher prices.

Connect middle home solutions to shared values: protecting the American Dream for families of all incomes, especially young people and seniors. Where we live shapes our lives and our long-term success–from the length and cost of our commutes to where children go to school. Middle home choices in neighborhoods close to jobs, schools, transit, parks, and businesses expand opportunity for all. Re-legalizing middle housing as an option would put many young people on a better track to build their American dreams and keep many seniors from losing what they’ve built.

Paint a picture with photos and descriptive, plain language (not buzz words): Instead of jargon (like “density,” “units,” “zoning” and “multi-family”), show what solutions look like and name specific home types—duplexes, triplexes, small apartments. These kinds of homes are familiar in many neighborhoods; most people can imagine them fitting into their community and providing options for their neighbors. Showing what they look like helps tame exaggerated fears.

Find more housing affordability talking points here and our affordability policy analysis here.

Comments are closed.