UPDATE 1/18/19: The bill—SB 5334—dropped today.

In Seattle’s post-recession boom, condominiums have mostly gone missing from the construction party. The reason? Apartments offered a better return on investment relative to the risk. And one factor that jacks up risk for condo development is Washington state’s onerous condo warranty law that encourages costly lawsuits over construction defects—real or imagined. The conventional wisdom: if you build condos, you’ll get sued.

Laws to protect condo buyers from shoddy construction can serve the public interest. But Washington’s law puts condo builders at so much risk that all told, it’s doing the opposite.

Early this year, state lawmakers will have the opportunity to give condo production a shot in the arm by reining in frivolous lawsuits. The proposed bill would tighten what qualifies as a warrantable defect, and it would more explicitly shield condo association board members from personal liability so they would be less inclined to file lawsuits just to protect themselves.

As if on cue, recent shifts in the real estate market have sparked a condo resurgence in greater Seattle. But that’s no excuse to leave the condo law broken. The costs of insuring a condo building against a potential lawsuit, or defending against one if sued, are about the same regardless of the condo’s price. So the status-quo law puts a bigger hole in the budget of lower-priced condo projects. In other words, dysfunctional condo law slows construction of the homes most needed in Washington, as across Cascadia: less-expensive ones.

Even subsidized affordable condo projects get hit: one Seattle nonprofit developer had to shell out about $400,000 extra for insurance that covers lawsuits—roughly the production cost of one and a half condo units in the building. The fixes soon to be on the legislative table would help put an end to the condo law’s scourge and bring more home ownership options to communities throughout Washington state.

How condos help affordability

Seattle called on the state legislature to revamp the condo warranty law in its 2015 housing affordability plan. How do condos help affordability? Though popular opinion derides them for their presumed extravagance, most condos don’t look like Frasier’s glassy pad with the Space Needle view. No, most condos are run-of-the mill apartments, filling a niche for people who wish to enjoy the advantages of home ownership but can’t afford—or don’t want—a detached house on a grassy lot.

According to Zillow, as of November in Seattle the median value of condos was $487,000, compared with $760,700 for houses. That’s 56 percent more for a house. Condos form the bottom rungs of the ownership ladder, from which households can climb over the years, trading up for larger or more valuable homes, and accumulating wealth.

On the flip side, when people downsize into condos, the houses they vacate relieve the upward price pressure caused by too many people competing for too few family-sized homes. But a city lacking condos strands many potential downsizers in their big houses, even if they don’t need the space.

The years of the missing condo and the recent comeback

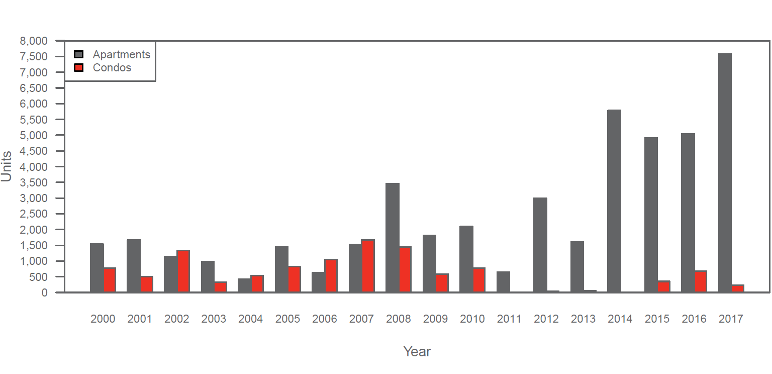

My Sightline colleague Margaret Morales previously documented the dearth of condo construction in Seattle: from 2012 to 2017, fewer than 4 percent of all new dwellings were condos while more than 80 percent were apartments. The chart below shows production of condos and rental apartments for Seattle and neighboring cities Bellevue, Kirkland, and Redmond. A University of Washington report documents a similar story in several western US cities.

The condo lull has been a national phenomenon in the US, but sales data reported by the Seattle Times indicate that the shortage is more severe in Seattle than in other high-cost cities:

“Just 19 percent of homes for sale in Seattle are condos, lower than other pricey markets such as New York (52 percent), Chicago (48 percent), Washington, D.C. (41 percent), San Francisco (37 percent), San Diego (33 percent), Denver (23 percent), Los Angeles (22 percent) and San Jose (20 percent).”

Remarkably, in 2018, greater Seattle saw a great awakening of condos, with some 6,000 units in the pipeline over the next four years. If most of the planned condos get built, 2022 will surpass the previous peak of 1,674 in 2007 (see bar chart above). Check out this article from marketing firm Realogic for some new condo examples. At least a half dozen projects originally planned as apartments have converted to condos prior to construction.

The economics that hold back condos and how the scales can tip

What happened in the Seattle area? Across the US, condo development suffers financial handicaps that make apartments more attractive. (The opposite is largely true north of the border.) Tax rules treat revenue from selling new condos as ordinary income, which is taxed at a relatively high rate. In contrast, apartment developers can refinance or hold their buildings to avoid a big tax payout at completion. In particular, large institutional investors tend to prefer apartments over the short-term, heavily taxed condo alternative—especially when condos are saddled with the risk of lawsuits. Also, higher quality standards for condos raise construction cost.

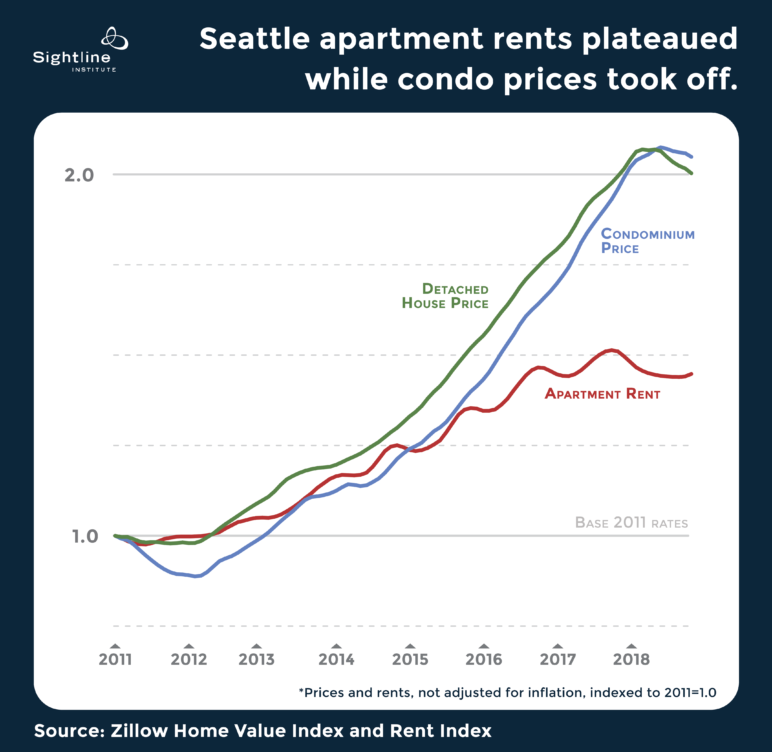

The graph below shows how the prices of detached houses and condos, and the rents of apartments, have changed in Seattle since 2011, according to Zillow’s price and rent indices (not inflation adjusted). Starting in 2015, prices began rising faster than rents. Then, in mid-2015, condo prices started climbing faster than house prices: in August 2015, the average house price was 74 percent more than the average condo price; as of November 2018, the house premium had dropped to 56 percent, reflecting unmet condo demand. Together, the price-boosting condo shortage and cooling interest in the saturated apartment market explains the recent blossoming of new condo projects.

The condo law and the damage done

Over the nearly three decades since Washington passed its Condominium Act, policy wonks and builders have denounced its chilling effect on condo production throughout the state. The law sets a higher construction warranty standard for condos than for houses or apartment buildings. Over time, it has spawned a legion of attorneys who specialize in persuading condo association board members to sue their builder for something—anything!—because it’s better to be safe than sorry when the statute of limitations is running out. The lawyers have gotten so good at inciting lawsuits that developers take it as given that they’ll get hit with legal action. Sometimes the claims are legitimate, of course. Because most lawsuits settle out of court, there’s little publicly available information on claims and their outcomes.

Almost all condo developers in Washington state buy additional insurance to cover the risk of construction defect lawsuits. Insurance cost varies, reportedly falling in the range of $5,000 to $35,000 per unit in the building. The need for insurance adds cost to for-profit and nonprofit condo development alike, though publicly subsidized condos are a rarity in Seattle. Affordable housing developer Homesight paid nearly $800,000 for insurance on a 102-unit, mid-rise condo, while insuring the developer and contractors for a similar building with rental apartments inside instead of condos might cost around $400,000. Homesight’s added insurance expense could have paid for the construction of one and a half of the building’s condo homes.

It’s not just developers. Most contractors also fork out extra for condo insurance. One Seattle architect told me they add a 10 percent surcharge to their design fee to compensate for the expense and potential legal hassle. Some designers and contractors simply refuse to work on condos because of the lawsuit risk, reducing competition and driving up construction costs. Likewise, some investors and lenders won’t touch condo projects, inflating the cost of financing. All of these costs get passed on to the condo buyer.

That is, unless buyers aren’t willing to pay that much. If so, the builder probably wouldn’t have pursued the project in the first place. Unfortunately it’s impossible to estimate how many new condo homes never got built because the condo law piled risk and expense on builders, but Seattle’s condo drought, even during a period of sky-high real-estate prices, suggests it is a big number.

Previous efforts to make condo laws less onerous

Other states have faced the same problem, and in recent years, several of them decided to to address it by updating their legislation, including Colorado, Idaho, Minnesota, and Nevada. Initial reports from Denver are encouraging: condo starts in the second quarter of 2017, after Colorado’s reform, were up 112 percent over a year prior.

Washington has faced a broken Condominium Act for three decades, and in 2005, the state passed a set of amendments to improve it. One provision was intended to ease risk by standardizing insurance, but the private insurance market has not offered policies that meet the state guidelines. Policymakers hoped to emulate British Columbia’s insurance system that supports condo construction by establishing predictability for builders (good explanation here). Another provision established a new requirement for inspections to ward off water infiltration damage. The post-recession condo drought indicates that these reforms weren’t enough.

Early in 2018, Washington lawmakers proposed a bill that would have required approval from at least half of a condo building’s owners before a lawsuit could be filed. It also would have made it easier for builders to avoid court by simply repairing defects. The bill didn’t make it out of committee, partly because some legislators thought it rolled back liability too far.

Washington’s latest attempt to fix its condo law

Representative Tana Senn and Senator Jamie Pedersen are leading the effort on a bill for Washington’s 2019 session that aims to quell frivolous lawsuits in two ways. It reduces the incentives for condo association board members to file lawsuits by explicitly stating that they cannot be held personally liable to pay for defects they did not sue builders for causing. And it prunes out bogus claims by refining the definition of a warrantable defect.

Condo board members are just ordinary people, elected by their neighbors and rarely legal experts. Understandably, they are defensive about their own liability for defects in their buildings. But Washington’s law leaves some of them worried about having to pay personally to repair defects—sums that can run into the millions of dollars. Some lawyers advise board members that the only way to protect themselves is to sue the builder for every possible defect that may arise, a scenario that begets a lot of lawsuits. In fact, under the current law, in all but cases of extreme negligence board members cannot be held liable. But to put the issue to rest, the draft bill carefully spells out board member immunity.

To refine the definition of a defect, first, the proposed bill strikes the requirement that construction must comply “with all laws,” in order to stop absurd, nitpicky disputes: owners suing, for example, because someone was able to find two nails spaced 13 inches apart when the building code says it has to be 12. Second, it replaces “sound” construction standards with “generally accepted.” That difference may not sound like much, but in the arcane world of The Law, it matters. It shifts the burden of proof to the appellant, and keeps cases from devolving into protracted battles of competing expert witnesses.

How much would these incremental tweaks spur condo construction? Multiple economic factors influence a developer’s go/no-go decision, but every bit of reduced risk and cost helps tip the scales toward “go.” Meanwhile, condo buyers can put more of their dollars into the actual home they’re purchasing—dollars that otherwise would have lined the pockets of lawyers and insurance companies. Enacting these fixes promises lots to win and little to lose. (For other ideas to tame the condo law and boost construction, see the appendix below.)

Ending condo warranty fishing expeditions

Washington’s onerous condo warranty law is exacerbating its affordability squeeze, particularly in the state’s biggest city, where the condo drought has put home-ownership out of reach for those who can’t afford a detached house. Despite the recent surge in new condo projects, the law still needs fixing. The risk and cost it inflicts creates an especially high barrier to lower-priced condos, which are in shortest supply.

No need to throw the whole thing out—condo buyers deserve protection. The proposed state bill for 2019 would make a smart set of incremental changes intended to thwart the “fishing expeditions” that lead to far too many frivolous lawsuits. If they can get this done, lawmakers will help resurrect an essential piece of Washington’s housing affordability puzzle.

APPENDIX

Other potential fixes to ease risk and boost condo construction

Strengthen right to repair: For cases in which the builder is clearly at fault, a common sense solution is to let the builder fix the defect, saving both sides the time and expense of a legal battle. Washington’s law already has such a “right to repair” provision, but owners can reject the builder’s repair proposal—all the more likely when there’s bad blood between parties. California mandates that if mediation fails owners must accept repair offers, but allows the owner to choose a different contractor from a list that the builder is obligated to provide.

Refine the definition of a defect: Minnesota defines a construction defect to only include those caused by initial design or improvements done by the original builder; Nevada defines it to only include those posing unreasonable risk of injury. Ideally the definition is precise as possible without being too narrow. Nevada’s would appear to push into the “too narrow” realm—does a leaky roof pose risk of injury?

Extend requirements for owner approval: In Colorado and Minnesota, a majority of the condo owners must vote in favor of proceeding with a lawsuit. Presumably, this discourages iffy lawsuits that don’t garner much support among owners.

Limit remedies to specific performance of repairs: This approach could reduce the incentive to go after cash awards when repairs aren’t actually necessary, though it wouldn’t stop disputes over the cost of repairs.

Cap attorney fees paid to plaintiff’s counsel: This provision could reduce lawyers’ incentive to pursue baseless litigation. However, it would be politically challenging to pull off: no such caps exist in many other areas of law. Alternatively, state condo law could ban so-called contingent fees, those based on a percent of the settlement.

Remove the right of appeal of arbitration awards: This reform would make arbitration more reliable for avoiding court, but would require changing a separate state law. As an alternative, purchase contracts can provide for binding arbitration to prevent appeals.

Loosen restrictions on pre-sale deposits: Industry insiders with whom I spoke flagged another factor that may put condos at a disadvantage in Washington: the 5 percent limit on non-refundable deposits for pre-sales and the prohibition on using those funds to help finance construction. In Vancouver, BC, for example, typical deposits fall in the 15 to 20 percent range. Buyers with money to lose are less likely to bail if the market sours, and that reduces risk for the builder. Laws in most states require builders to hold the whole deposit in escrow, but Florida only mandates that for 10 percent of the purchase price. Florida builders can use any part of the deposit above that 10 percent as cash equity to help secure construction loans, and that helps more condo projects get off the ground.

Comments are closed.