The fight to strike down apartment bans has arrived in Oregon’s legislature.

On Friday, Willamette Week broke some news: Oregon House Speaker Tina Kotek has been working for several months on a bill that’ll require all but the smallest Oregon cities in urban areas to re-legalize up to four homes per lot—a lower-cost housing option that was quite common in the early 20th century but was gradually banned from most parts of most cities.

We’ve had a lot to say about proposals like this before and we’ll have much more to say about this one in the months to come.

But just for today, let’s set aside the housing policy implications and focus on a slightly different question: Would re-legalizing fourplexes everywhere be good for bicycle transportation?

It very much would be.

As BikePortland.org put it 11 years ago, proximity is key to our future. More than bike classes, more than courteous driving, more even than comfortable infrastructure, the number-one way to make bike transportation work for the life of an ordinary Cascadian is to make the trips we have to take shorter.

Making it legal—not mandatory, just legal—to build homes closer to each other is the way to do this.

Legalizing more housing creates more proximity twice.

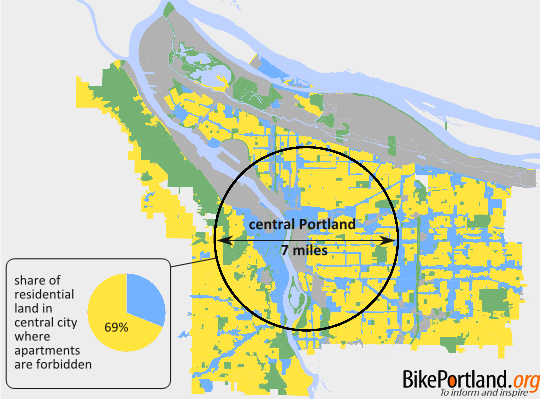

First and most obviously, it creates proximity because it lets more people (and also more varieties of people) choose to live closer to current destinations like jobs, parks, schools, grocery stores, shops, parks, quality transit stops and (oh, yeah) their family and friends. Two weeks ago, an economic report on Portland’s fourplex re-legalization proposal estimated that 87 percent of the new, smaller and relatively cheaper homes built would go into the lower-density neighborhoods up to roughly 3.5 miles from the city center.

Those are the exact same neighborhoods I called out in a 2014 BikePortland piece titled “maybe this is why you can’t afford to rent in the central city.”

These are also, of course, the Portland neighborhoods with the best bike infrastructure. We should be improving biking everywhere, but we can also make our existing investments go further by letting more people live near them.

The second reason re-legalizing duplexes, triplexes and fourplexes creates proximity is that simply by existing, homes help create more new things near them. TriMet can’t justify upgrading a bus line to frequent service until a lot of people live fairly close to it. New Seasons can’t justify opening a new grocery store—and Fred Meyer may not be able to justify keeping an existing grocery store open—unless there are a certain number of people living near it.

Every neighborhood coffee shop and dive bar in the city relies hugely on the people who live close enough to walk or bike there and back without hardly thinking about it.

More homes => more people => more coffee shops and dive bars within biking distance => more biking.

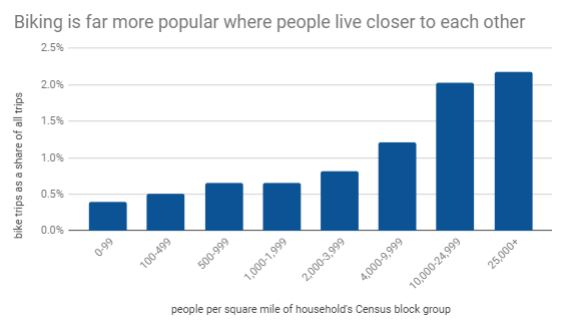

You don’t have to take my word for it. It’s right there in the National Household Travel Survey:

This is the flip side of the phenomenon my colleague Margaret Morales recently observed about backyard cottages. She calculated that adding 7 more homes to each standard city block of 21 lots would reduce average driving per household on that block by about 1,000 miles per year.

(Or for more evidence in various contexts, you could look here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, and here.)

One thing to notice about the chart above is that the difference in biking between 17,500 people per square mile (Portland’s Northwest 23rd Avenue, with lots of the old mid-scale housing that has since been mostly banned) and 27,500 (the south side of Portland’s downtown, with skyscrapers) is much less than the difference between 7,500 people per square mile (a lawn-and-driveway area like Beaumont-Wilshire) and 17,500 people per square mile.

In other words, if we want lots more biking, we don’t have to put towers everywhere (though that wouldn’t hurt, either). We just have to transition into cities with many buildings that are a few stories tall and attached to each other.

Hmm, sounds somehow familiar.

None of this is to say we shouldn’t also be building awesome protected bike lanes and off-street paths and traffic-calmed side streets. Cities in northern Europe, South America and southern China prove that the magic formula for lots of biking is to combine proximity with great streets.

After years of stagnation, Portland is finally doing more to improve its streets. The logical next step is to make it possible for more Portlanders to use them a little bit less.

john Neff

Fourth from last paragraph, you switch from pop/sq mile to pop/acre…

Kelsey Hamlin

John, thank you for pointing this out! That discrepancy is a concern, and I’m making sure we get it addressed. Talking with the relevant researchers right now to update the piece.

Michael Andersen

Thanks, John. My typo, fixed.

kac

The premise of this piece is based on an untested assumption, viz., that proximity in and of itself will induce a significant minority (or perhaps a majority) of commuters to ride bicycles. Would even more density say in the form of high-rise apartments yield even more bike commuters? What if some/most of the potential inhabitants of these new buildings opt instead for automobiles and park them on residential streets? What are the effects on cyclist safety of narrower “greenway” bypasses of major arterial routes due to more parked cars and/or drivers? Perhaps the data to support the hopeful (or maybe fanciful) predicate for this article can be provided to readers by the author.

Swagatika Rath

This is valuable comment for us..