Voters often feel their influence is more powerful at the local level than over state or federal decisions. A voter can implore their city council person to fix a pothole or change the noise ordinances and see a tangible result. A voter can elect a school board member who promises to address racial inequities in graduation rates and follows through on that promise. One local elected official can have a major influence on the shape of an entire community, but individual voters often don’t see that same cause-and-effect beyond city or county jurisdictions.

Local elections for city councils, county councils, and school boards are often nonpartisan, so voters might look to other signals, including race and ethnicity, to determine whether a candidate will represent their life experience and views. A recent look at 20 Oregon city councils, 20 county councils and 20 school boards reveals a striking disparity between the makeup of the population and local elected governing bodies. Some Oregon cities with significant populations of color have no representatives of color on school boards, or on city or county councils. One school district has a majority of students of color but no one of color on the school board.

The data, taken from the US Census Bureau, Oregon school districts, and local court jurisdictions’ websites, is one of many signals that the voting system does not yield representative elected bodies. In most of these elections, a slim majority or a mere plurality (less than half) of the vote equates to 100 percent of representation, leaving the rest of voters with no representative of their choice at the table.

To give all residents a chance at fair representation, local jurisdictions need to be able to adopt voting methods that give all voters a voice. An Oregon Voting Rights Act, which could be introduced in the 2019 legislative session, would open new paths for local jurisdictions to switch to fairer voting systems. The Act would open the door for voters to adopt a different voting system and elect officials in proportion to their share of the vote—if one-third of voters want a particular candidate, said candidate could win one seat on a three-person body. The winner-take-all systems in place today mean a candidate with only one-third support will most likely lose.

Districts aren’t necessarily the solution

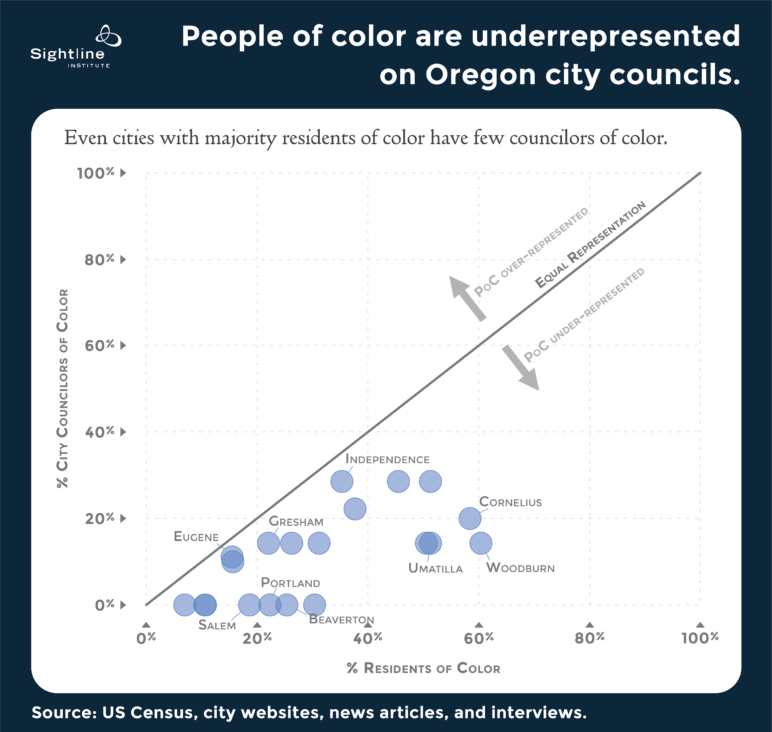

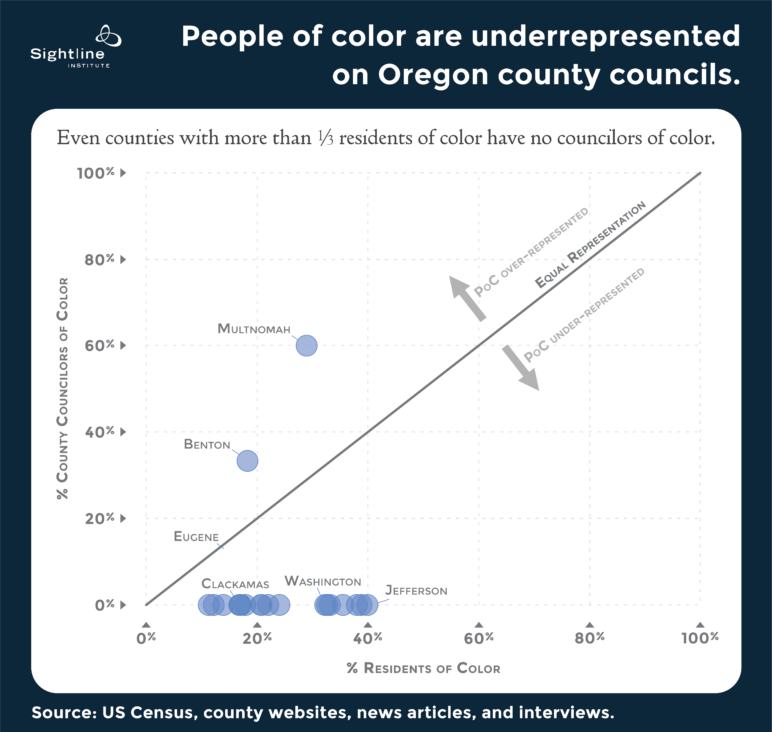

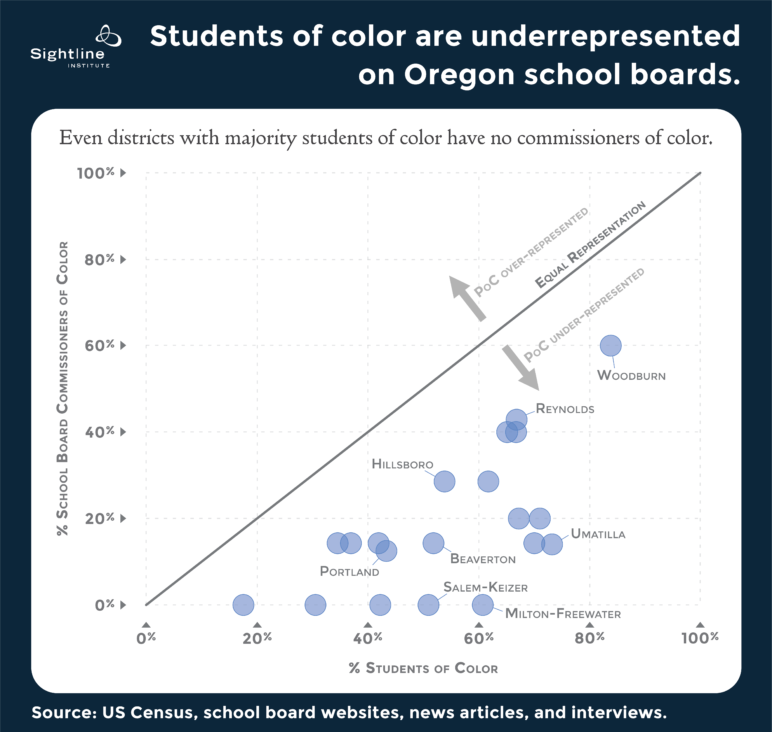

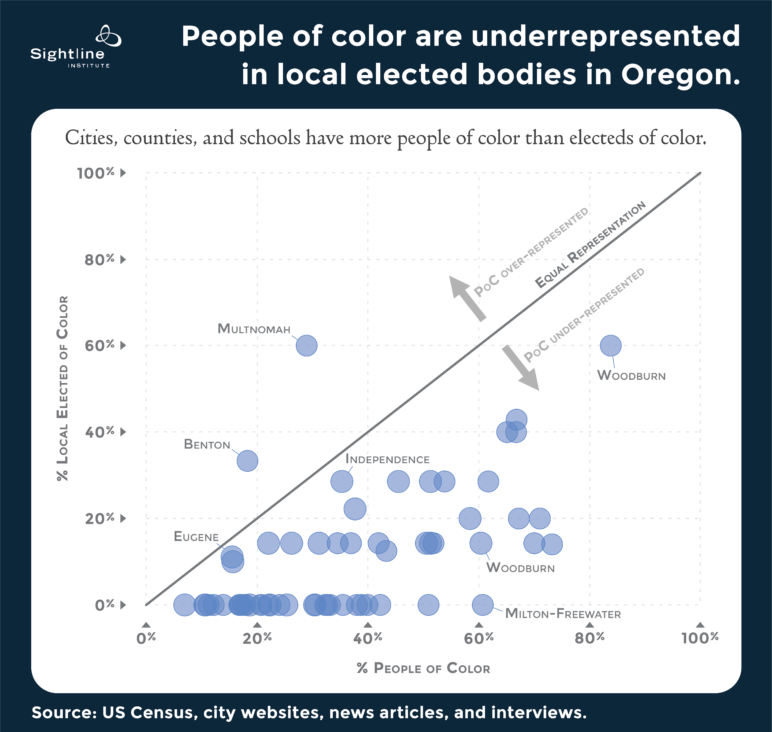

To get some insight into the magnitude of misrepresentation in Oregon localities, we looked at ten of the most populous and ten of the most racially diverse cities, counties, and school districts in Oregon. Of the 60 local Oregon bodies examined, all but two underrepresented people of color. In the graphs below, all bubbles below the gray diagonal line indicate people of color are underrepresented in that jurisdiction (there are more people of color or students of color than there are elected officials of color).

When some reformers see underrepresentation of racial minorities, they think the solution is districts. Examples like Yakima, Washington, show how switching from at-large elections (where everyone runs city-wide) to districts (where candidates run in a smaller district) can help Latinxs win elections. Unfortunately, that approach relies on racial segregation to succeed. When a racial group is concentrated in a certain part of the city and the redistricting process draws the lines of a district around that area, they can create a “majority-minority” district. That’s a district where a racial minority makes up the majority.

Unfortunately, districts are not a cure-all. Several of the cities and counties below already use districts (a.k.a. wards) and more than half of the school district nominate by zone, but they still do not elect a representative number of people of color. The underlying problem is winner-take-all elections. And the solution is multi-winner, proportional elections to give every voter more choice and more voice.

20 Oregon cities

As of December 2018, in 7 of the 20 Oregon cities, there were no people of color on the city council. In 4 of the cities, people of color made up more than 13 percent of the residents, meaning a reflective 7-member council would have included at least one person of color. In four of the cities that did elect at least one person of color, electeds of color were a much smaller portion of the council than of the city’s population as a whole. For example, 60 percent of residents of Woodburn are people of color, but only one out of seven city councilors is a person of color. Similarly, a majority of residents of Umatilla are people of color—including 43 percent of the population who are Latinx—but just one city councilor is Latina. The other six are white.

Eugene comes closer to a racially representative council—one out of its nine councilors is a person of color, as are more than 15 percent of voters. Independence, in Polk County, also has relatively reflective representation. One-third of the people living there are of color, and two of seven council members are of color.

20 Oregon counties

In 18 of the 20 counties we looked at, not a single person of color served on the county council as of December 2018. Using districts didn’t necessarily help counties elect a more racially representative council, either. Three of the counties that didn’t elect any people of color used districts, while Benton County used at-large elections to vote in two Latinx commissioners (we only coded one of them as a person of color as the other states that while she is culturally Latinx, she has benefitted from the privilege of appearing white). But three other counties, Hood River, Lane, and Washington, elect by district and still don’t have any commissioners of color.

Starting in January 2017, Multnomah County had a remarkably diverse board consisting of five women, including one African-American, one Asian-American, and one Latina.

20 Oregon School Boards

Oregon student bodies and school boards are more racially diverse than cities and counties. Although none of the school boards had as many board members of color as they have students of color, some got close. For example, Woodburn School District in Marion County has 84 percent students of color and three of its five commissioners are of color. In Reynolds School District in Multnomah County, two-thirds of the students are of color, as are four of its seven school board members.

On the other hand, an all-white board oversees the Milton-Freewater Unified School District in Umatilla County, where almost 60 percent of the students are of color. Salem-Kaizer, in Marion County, has majority students of color but no commissioners of color.

Put it all together—60 Oregon jurisdictions

Of all 60 Oregon cities, counties, and school boards, only two cities fall above the equal racial representation line. In all others, people of color are somewhat are very much underrepresented.

How can local jurisdiction improve racial representation?

Winner-take-all elections, in which one person wins the race and all other candidates lose, exclude voters in the minority. A city might elect seven councilors-at-large (from the whole city), but each one is running in a winner-take-all race. Only one person can win for position 1, one person for position 2, and so on. Districts are also winner-take-all races—only one person wins from each district. Voters in the majority can elect the one winner for the district, leaving voters in the minority with no representative.

The solution is multi-winner races with some proportional form of voting. When candidates run against each other in a pool, and voters use a proportional method to pick the top several candidates, voters who aren’t in the majority can nonetheless elect their minority proportion of the representatives. A third of the votes secures a third of the seats. And voters in the minority have a voice. Hundreds of US jurisdictions have adopted semi-proportional methods (mostly as a result of a US Voting Rights Act challenge to their lack of racial representation) and have subsequently elected racially representative councils.

Read the next article in this series to see how Oregon cities could make the same shift.

Thanks to Trygve Madsen and Shalyn Pugh-Davis for their help in researching this article.

Notes about the Data

- You can see the tables of data here.

- To determine the percentage people or students of color, we summed every census category other than “white alone / not-Hispanic.”

- To determine whether electeds were people of color, we looked at names, photos, bios and other public statements. When we could not confirm, we contacted the officials directly to ask if they identify as a person of color. In a few cases, particularly for school board members, we were unable to definitively verify in which cases we generally erred towards classifying them as white.

Comments are closed.