As cities across North America consider re-legalizing duplexes, triplexes and fourplexes in low-density residential areas, housing advocates need to start asking new questions:

How many of these small, attached, relatively affordable homes will actually get built?

Where will they get built?

And for city leaders who face competing political pressures to minimize demolition but also maximize housing opportunity, is there some way to find a balance?

A much-anticipated analysis released Wednesday by the city of Portland sheds some light on those questions. Housing advocates everywhere deserve to understand what it found, because Portland may have stumbled across a formula that could work well in many cities in Cascadia and beyond.

The report from local firm Johnson Economics, hired by the city’s planning bureau to analyze a tentative recommendation from its planning commission, explored the math of Portland’s innovative proposal to do two things at once:

- Cap the size of new buildings.

- But set a slightly lower maximum size for a one-home building than for a duplex, and a slightly lower size for a duplex than for a triplex or fourplex.

In other words, Portland’s idea is to give developers of small projects a reason (other than the goodness of their hearts) to build the sort of buildings the city needs most: those with more homes inside them.

At most, a market-rate triplex (or fourplex) on a 5,000 square foot lot could be up to 3,500 square feet, which is about 20 percent smaller than this Northeast Portland triplex:

1,217 more homes per year, mostly small and attached; only six more demolitions per year

Portland’s two-pronged proposal, Johnson calculated, delivers a lot of new housing.

The combination of sticks and carrots (none of which would require any public subsidy beyond simple enforcement) would lead to 24,333 more homes over the next 20 years than the status quo, which allows small, old homes to be replaced by big, expensive ones and essentially by nothing else.

That’s 14 times more additional housing than under the city’s previous proposal, under which duplexes would have had the same size cap as a one-home building. An earlier analysis found that the earlier proposal would create only 87 net new homes per year, drawing criticism from both pro-housing and anti-demolition activists at planning commission hearings.

The new proposal, meanwhile, would increase the demolition rate by just 8 percent over the status quo—six more homes per year.

How is this possible? Because the proposal would sharply reduce the number of times a landowner spends half a million dollars to replace one house with one house.

Or as Portland pro-housing advocate Holly Balcom put it, it’d make every demolition count.

Analysis: Low-price, lower-income neighborhoods would see no demolition

Another bit of news in Wednesday’s report: creating a small size bonus for duplexes and triplexes wouldn’t increase demolition rates in Portland’s lowest-income areas.

The science is not yet clear on whether redeveloping a property to add more housing accelerates displacement on its block any faster than, say, renovating a property (which also tends to eventually replace lower-income people with higher-income people, but has never been banned).

Still, there’s a legitimate question of whether poorer households—those most vulnerable to regionwide housing shortages—might end up bearing the burden of changes from zoning reform intended to (among other things) reduce Portland’s long-term housing shortage.

Johnson concluded that poorer neighborhoods wouldn’t see any more demolition, simply because newly-built homes in low-amenity areas couldn’t sell or rent for enough to cover the cost of construction, let alone buying and then scrapping a habitable home. The additional size and unit allowances proposed by the city wouldn’t change that basic fact.

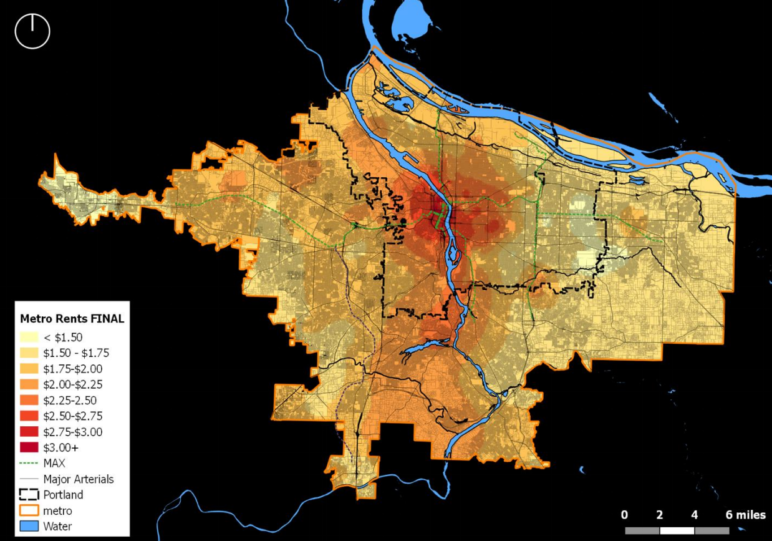

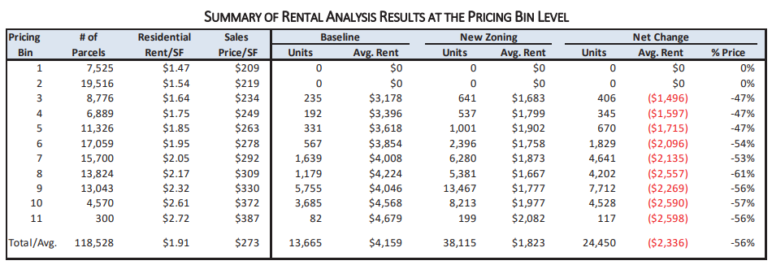

According to Johnson, new homes—and all six of those additional demolitions per year—would be economically possible only in areas where new housing can command rents above $1.64 per square foot—almost nowhere east of Interstate 205, in other words. In Portland, the neighborhoods most likely to see more housing would be those where new homes rent for $2.32 or higher: west of 82nd, north of Holgate, south of Fremont, north of Beaverton-Hillsdale Highway. (Those are the so-called pricing bins labeled 9, 10 and 11 in the table below.) The new market-rate homes in those areas wouldn’t be cheap per square foot—no new market-rate housing is. But Johnson calculated that the new homes, most of them smaller homes in duplexes, triplexes or fourplexes, would be an average of 56 percent cheaper than the big detached homes that would be built there under current zoning rules.

The new market-rate homes in those areas wouldn’t be cheap per square foot—no new market-rate housing is. But Johnson calculated that the new homes, most of them smaller homes in duplexes, triplexes or fourplexes, would be an average of 56 percent cheaper than the big detached homes that would be built there under current zoning rules.

In the same way old triplexes and fourplexes still standing do today for prewar neighborhoods, this new generation of small, attached housing would open the doors of currently exclusive neighborhoods to more people: different ages, different incomes, different wealth levels. Over the long term, it’d integrate the Portland neighborhoods closest to jobs, schools, and public transit.

This issue heads back to Portland’s planning commission for a final vote in the spring, then to its city council in mid-2019. (That’s the latest schedule, at least.) It’s unclear where the city council will come down on one crucial question: striking a politically acceptable balance between allowing more citywide displacement by not building enough, and allowing more demolition in order to add more homes.

But this study, at least, suggests to me that the city’s latest proposal is pretty close to a home run.

Comments are closed.