The big, hard-fought housing ballot issue that Portland-area voters approved this month set aside 10 percent of its revenue—$65 million—specifically for low-income-affordable housing near transit lines.

But as the same regional government draws up plans for the region’s next light-rail line, it’s also been quietly preparing to give the rest of the Pacific Northwest an object lesson in what not to do.

It’s weighing whether to dedicate $168 million or more to free parking garages.

Greater Portland’s “Southwest Corridor” line, as the route mostly along Barbur Boulevard and Interstate 5 is known, could become the most parking-heavy rail line in the history of TriMet, Portland’s regional transit agency. Tucked into one of the scenarios for the $2.7 billion, 13-station project are five free-to-use parking garages with up to 3,350 structured parking spaces among them.

Even in its leanest scenario, TriMet currently expects to pour something like $100 million into these structures with 45-year lifespans at a time when autonomous vehicle experts are wondering whether anyone will use parking lots at all in 20 years—and a time when the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has given the planet 12 years to dramatically and permanently reduce its energy use or face decades of deepening climate-driven catastrophe.

Last month, Marianne Fitzgerald, a longtime advocate for better transportation in Southwest Portland, described the cost of all that parking as “the biggest-kept secret.” No public documents associated with the project have estimated the cost to taxpayers of the new parking already being promised along the line.

Asked to estimate the likely cost to the public per parking stall, a spokesperson for Metro referred the question to TriMet. (The day after this post was first published, TriMet responded to questions sent Nov. 15 by sharing figures on hard cost estimates that would put total costs in the range of $50,000 per structured stall.)

Assuming the standard industry average of $50,000 per stall, 3,350 garage spaces would cost the public $168 million.

For comparison’s sake, that’s enough money to build or acquire roughly 1,000 below-market-rate homes along the line; to install networks of protected bike lanes for miles in every direction around each proposed rail station; or to double the scale of TriMet’s big 2018 regionwide bus service improvement for the next 12 years.

Oddest of all, the free park-and-rides are expected to generate so few riders that every parking stall TriMet builds digs a deeper and deeper hole in the transit agency’s finances.

Southwest Corridor is on track to be among the most parking-heavy rail projects in Portland history

Free-to-use park-and-rides are so central to the way TriMet thinks about its mission that when it listed the major rail projects in its most comprehensive account of its own history, park-and-ride spaces were one of the five facts about each rail project that the agency felt were worth listing. (Not mentioned: projected or actual ridership; number of bus lines linked; number of homes or jobs served.)

TriMet’s most parking-heavy rail line until now was its Westside expansion in 1998, which was 50 percent longer than the proposed Southwest Corridor line and included seven more stations. At opening, that project created 3,613 parking spaces. (In the 2015 self-history linked above, TriMet put that figure at 2,733, but it now says the smaller figure was inaccurate.) That’s 181 parking spaces per new station. The Southwest Corridor is considering up to 269 spaces per station, a 49 percent increase. Even in its leanest parking scenario, it’d create 154 spaces per station, more than for any expansion except the Westside.

TriMet’s focus on free park-and-rides has continued despite the fact that, on an average weekday, its own figures show 38 percent of MAX park-and-ride parking stalls sit empty.

If the Southwest Corridor’s future park and rides were to have the same parking ratio long-term, it’d mean TriMet spent as much as $64 million—again, almost the entire regional budget for acquiring transit-oriented affordable housing—to build parking spaces that are available for free next to a frequent rail line but sit empty anyway.

Parking garages are ridiculously expensive

Many people do not realize that every stall in a basic parking garage costs about $50,000 to develop and construct.

That’s not driven by bureaucratic process or union labor; it’s an estimate for private projects. It’s simply the cost of buying land, finding cash, and laying concrete floors on top of concrete pillars strong enough to hold many thousands of pounds of steel.

Rick Williams, perhaps Portland’s leading parking consultant, told me each stall in a new local parking garage ranges from $45,000 to $60,000, with more attractive garages—like the gleaming car palace at TriMet’s Park Avenue station, built in 2015—coming in at the higher end or above. For TriMet’s never-built MAX extension to downtown Vancouver, which was once supposed to open in 2019, a pair of park-and-rides there would have been expected to cost $55,000 to $61,000 per stall.

But let’s assume each stall can be built for $50,000. Do the math, charitably assume a vacancy rate of just 20 percent, and it turns out that over the 45-year initial life of each parking space, TriMet is spending about $5.34 for every weekday the space will be used. (This doesn’t include the costs of either capital or replacement.)

In other words, taxpayers are handing out the equivalent of an entire career’s worth of free transit to anyone, as long as they show up to one of TriMet’s garages with a car.

If only there were other, more useful ways for a public transit agency to spend vast sums of money!

Free park-and-rides don’t even lure in very many riders

There’s one exception to TriMet’s sad track record of spending tens of millions of public dollars on empty park-and-ride stalls: its newest line, the Orange Line through inner Southeast Portland and Milwaukie. That line has two park-and-ride garages with 719 spaces between them, and both are usually 100 percent full.

If free park-and-rides were the secret to strong rail ridership, building them might plausibly make sense. Unfortunately, they aren’t.

Here’s the thing: Those two parking garages deliver less than 1,000 additional riders per day. And TriMet’s Orange Line is in desperate need of many more riders than that.

Based on the projections TriMet submitted in its federal government application and its latest ridership figures, the Orange Line has spent the last two years missing its ridership growth trajectory by 62 percent.

(The numbers: In 2010, TriMet projected 22,770 rides to and from for the Orange Line’s 10 stations south of downtown on an average 2030 weekday. The first spring after it opened, in 2016, the figure was 10,225, far below the projection of 17,000 weekday riders in year one; as of spring 2018, ridership was 10,912. That’s annual growth of 344 weekday rides … 62 percent below the growth rate needed to hit the 2030 target.)

Why has ridership growth on the Orange Line been so weak? In part, because even during one of the biggest booms in Portland history, there was little housing being built along it. In some cases, that’ll be a matter of time. But sometimes it’s due to exclusionary zoning that makes it illegal to build apartments near its stations, like at the 17th and Rhine station; and sometimes it’s also due to park-and-rides eating up the precious developable land next to the station, like at the Tacoma station.

Most rail passengers come from two places: buses and buildings

TriMet’s passenger counts show that when it comes to maximizing ridership, free parking garages pale in comparison to integrating rail with a grid of frequent-service bus lines—and simply making it legal for people to put up nearby buildings where they can live or work.

There are 24 light rail stations on the trunk lines within Portland’s pre-automotive core, from the central city east to 82nd Avenue. Served by multiple MAX lines, they’re the heart of TriMet’s rail system and the source of half its boardings—these stations are twice as busy, on average, as the rest of the system.

But these highly productive stations have a grand total of zero park-and-rides. Instead, their secret is that the streets and buildings around them were mostly developed before the age of mandatory driveways and widespread low-density zoning.

We haven’t lost the technology to build our cities this way. Along the Blue Line in Hillsboro, TriMet’s Orenco Station is a widely praised example of building for transit in the suburbs. It’s also one of the highest-ridership stations in TriMet’s system to be served by a single MAX line—thanks mostly to all the nearby homes and jobs. (Orenco also has a small park-and-ride lot. It’s usually half-empty.)

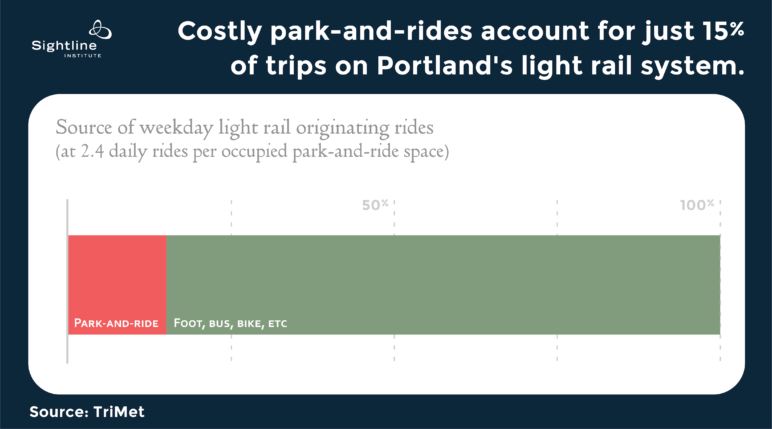

Metro’s own projections show the proposed Southwest Corridor park-and-rides aren’t expected to make or break ridership, either. According to this slide from a City of Tigard presentation about the plan, TriMet and Metro expect park-and-rides to account for just 15 percent of trips on the new line—4,200 boardings per day—in 2035.

But what would ridership be like if we could spend $168 million on something else?

At the cost per home assumed by this month’s regional housing bond, that sum could pay for 1,000 below-market homes, many of them affordable to very-low-income residents—enough to triple the sum voters set aside this month for housing along new transit lines. Think of all the ridership those homes would generate—especially if they were integrated with new market-rate apartments along the new line, including on the lots that would no longer have to be dedicated to parking cars.

Or what about $168 million for bike infrastructure? At about $650,000 per mile, that’d be enough to fund 13 separate 20-mile networks of low-stress protected bike lanes to feed each of the 13 stations on the new line.

Or $168 million for bus service? That’d be enough to double TriMet’s 2018 regional service expansion, the biggest in its history, for more than 12 years.

The real force behind park-and-rides is probably politics

The staff at TriMet and Metro are gifted pros who know their work better than I ever will. So why, despite all of the above, are they contemplating so much waste?

Why, for that matter, have transit agencies in the Seattle and Vancouver metro areas also subsidized park-and-rides—though neither is as absolutist as TriMet about making them free?

There are probably three reasons.

For these local agencies, the most convenient justification is that federal transit grants have long rewarded park-and-rides. In the United States, federal programs have rewarded projects that pull cars off the road—not projects that keep cars off the road in the first place. A naive bureaucrat looking at a park-and-ride sees a building full of cars that didn’t drive downtown, and scores it as a victory; a wise one sees a building that might otherwise be full of people who didn’t have to drive anywhere at all, and scores it as a loss. Fortunately, the wise bureaucrats won out on this question in 2012, thanks to the federal transportation bill signed that year; the Federal Transit Administration now rates projects based on trips generated.

In any case, it’s looking less and less reasonable to plan local transit decisions around federal grants. As you can see in the table near the top of this post, the federal share of MAX funding has been falling steadily. And with the Republican Party’s policy establishment pushing hard to replace the New Starts program that funds most new US light-rail projects, the Trump administration has been all but refusing to actually award New Starts money approved by Congress. (In Republicans’ defense, some of them argue that New Starts is flawed because it creates perverse incentives to spend money on things that make no sense—which is exactly what’s been going on with park-and-rides. Other Republicans, of course, simply oppose federal spending on mass transit.)

The second reason transit agencies are tempted to build park-and-rides is that park-and-rides may help people trapped by their own car-head visualize themselves—or at least their neighbors—riding transit. That includes plenty of politicians and the mostly well-off peers who tend to shape politicians’ opinions. It may not be enough to make someone actually drive to a garage, but it might be enough to make them vote in favor of having the option.

The third reason is that by surrounding their stations with seas or towers of free parking, transit agencies reduce the chance that commuters “park and hide” instead—that is, drop their car at a nearby curb and hoof it into the station. This is annoying to nearby residents. But there’s a simple answer to this problem that doesn’t cost $168 million: if their cities and counties allow it, neighborhoods near transit stations can create parking permit districts that prevent nonresidents from parking on the street. Or if it wanted, a local jurisdiction could sell street permits to transit commuters and use the revenue for crosswalks, playgrounds or other nice things. When a transit agency builds a free park-and-ride instead, it makes such systems indefinitely impossible.

In the end, the staff of Cascadia’s transit agencies tend to be mostly interested in completing their projects. They know what formulas have worked politically for them in the past, and they’ll change nothing until the politics of those formulas cease to work.

That’s why it’s relevant that a growing number of transit boosters—from neighborhood advocate Fitzgerald to Portland’s planning commission to the group OPAL Environmental Justice Oregon—are singling out the large proposed park-and-rides as a waste of cash and space.

“The automobile is one of the most destructive aspects of modern life, and we’re catering to them still,” said Shawn Fleek, a spokesperson for OPAL. “It boggles the mind that a transit agency with a mandate to address climate change and move people around our region would want to put even more cars on our roads by installing parking structures with precious resources that could otherwise go to transit operations and construction.”

Applications to join the Southwest Corridor community advisory committee, incidentally, are due Dec. 7.

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this post miscalculated several ridership figures for the Orange Line; in its first two full years, that line missed its target growth trajectory by 62 percent, not 61 percent. It also failed to reflect the fact that in 2013 (after the Orange Line had been planned) the Federal Transit Administration revised its methodology to mostly eliminate perverse incentives to overbuild park-and-rides; the earlier version said this perverse incentive still existed. And due to an apparent error in TriMet’s historical records, the initial post understated the amount of parking built along the Westside Blue Line expansion, though the proposed Southwest Corridor expansion could still create far more parking spaces per station.

Comments are closed.