[content_box type=”border”]

Definitions

Bike-share is evolving rapidly. These are the three most common approaches, though hybrid versions and new twists seem to be popping up weekly:

Station-based: From the time Paris debuted the concept in 2007 until recently, “bike share” meant renting and returning bikes at docking stations distributed within a defined geographic area. Washington DC’s Capital Bikeshare and New York’s Citi Bike are two large and well-known examples.

Free-floating (dockless): In July 2017, “dockless” bike share made its US debut in Seattle. Private companies distribute self-locking bikes that can be located and unlocked with a smartphone, ridden to any destination in the city and parked just about anywhere, no station needed.

Hub-based: With this new take on station-based, “smart bikes” with GPS can be locked either at designated hubs or at conventional bike racks, typically for a surcharge. Portland and Boise are Cascadian examples.[/content_box]

Editor’s note: Uber announced Monday, Nov. 19, plans to launch its bike-share service after receiving its operating permit from the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) last Friday. The announcement was made after this article was originally published.

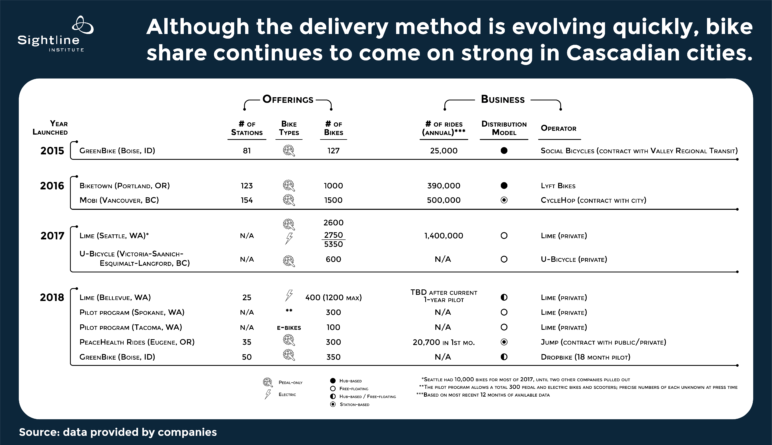

Electric scooter rentals may be getting all the buzz of late, but bike-share growth is still sizzling in Cascadia as cities work to find low-carbon solutions for the proverbial “last mile” from transit to destination.

Legacy systems—you know, those that are two or more years old—such as those in Portland and Vancouver are adding bikes and expanding territory, while smaller cities from Kelowna, British Columbia, to Spokane, Washington, are coming online.

For the purpose of comparison, I’ve highlighted the leaders in various categories of bike-share glory—or ignominy in a case or two.

Longest-running bike share operation

Had it survived, Seattle’s Pronto would have taken the prize. Launched in 2014, the station-based system had 500 bikes and 54 docks throughout the core of the city before the City of Seattle pulled the plug in March 2017. Instead, this honor goes to Boise, Idaho, whose GreenBike launched in April 2015. With 127 bikes and 81 stations, the Boise system is a division of Valley Regional Transit, developed with a federal grant in conjunction with the City of Boise and the Ada County Highway District, and sponsorship from local hospitals.

Newest bike share system

Bellevue—on the east side of Lake Washington from Seattle—stuck a toe in the bike share waters on July 31, opening its first protected bike lane while introducing 400 electric Lime bikes into the city’s transport ecosystem. Though its system is dockless, Bellevue hopes to get around the sidewalk litter problem by painting bicycle corrals on downtown streets and using geofencing to keep people from using parks for parking. The city is couching the nascent bike share option as a year-long pilot.

Runner-up for newest kid: Just before Bellevue, the Okanagan Valley city of Kelowna (pop. 128,000) in June began an 18-month pilot with Canadian bike-share company Dropbike, which has run similar efforts in Toronto and Montreal. Dropbike has created 50 “havens” where bikes can be parked without the extra fee that comes from parking them elsewhere. (The fee becomes a bounty that can be credited to the account of whoever returns the bike to a haven.)

Eugene, Oregon’s PeaceHealth Rides—winner of the longest name category thanks to the sponsoring health care network—rolled out in April. Begun at the impetus of the University of Oregon and operated by Uber’s Jump division, the system comprises 300 “smart bikes” that can be locked at one of 35 stations or at any rack within the service zone.

So new they’re still gestating: On September 4, the city of Spokane announced a two-month pilot program, with plans to launch a permanent system in the spring of 2019. For the pilot, which ended November 16, Lime was permitted to distribute a combined 300 conventional and e-bikes as well as electric scooters. The city is investigating the conditions it should set for companies seeking bike-share permits, as well as “the geographic boundaries for bike placement, the number of bikes that effectively fit our city, and how to manage bikes in the right-of-way.”

Tacoma, Washington, nipped at Spokane’s heels: On September 21, the city and Lime kicked off a 60-day pilot with 100 e-bikes and 250 scooters, that ends Wednesday. In October, Bird also was allowed to deploy 250 scooters. Lime has applied for a 60-day extension, which Tacoma appears prepared to grant as city leaders evaluate results before deciding whether and how to develop a permitting system.

Most aborted bike share operations

That distinction goes to Seattle, with three to date. In July 2017 , four months after pulling the plug on the dock-based Pronto network, the city became the first in the US to take free-floating, dockless bike share for a Spin—and an Ofo and a Lime. Those three private operators ultimately brought 10,000 self-locking bikes to Seattle street corners, parking strips, sidewalks … anywhere riders cared to leave them. At just $1 for a half-hour ride, Seattleites quickly took a shine to the orange, yellow and green bikes. The intended six-month pilot was extended to a year as the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) worked to develop new regulations and permitting fees for ongoing operations; during that time people in the city took about 1.4 million bike-share rides.

The Seattle City Council on July 30 approved an expansion of up to 20,000 bikes along with a permit fee per operator of $250,000 and a plan to build up to 200 new corrals for bike parking. Almost immediately, Ofo announced it would pull out of Seattle. Though it cited the new fees as a reason, the Chinese company already was in the midst of what became a wholesale divestment from US bike-share. Then in mid-August, Spin also complained about the permit fee as it left the city, though the company was in the midst of dropping bikes in favor of electric scooter rentals.

Lime, meanwhile, decided to stay put and filed for a permit, along with the bike-share divisions of ride-hailing companies Uber (operated as Jump) and Lyft. As of publication, Uber had announced its plans but Lyft had not. Meanwhile, absent competition, Lime upped its rates: Still $1 to unlock regular bikes, but now 5 cents a minute to equal $2.50 for a half-hour.

Largest number of bikes

Though it’s getting hard to keep up, it seems certain Seattle still leads. At one point in the early summer, Seattle had nearly a quarter of all the rental-system bikes in the US with 10,000. With the departure of Ofo and Spin, that dropped to nearly 5,000 remaining Limes.

Next comes Vancouver, British Columbia’s Mobi, a station-based system with 1,500 bikes docked at 154 stations in an area that includes the downtown peninsula, bounded by Arbutus Street, 16th Avenue and Victoria Drive. Portland’s BikeTown is next, with 1,000 bikes and 123 docking stations.

Largest public subsidy

This almost certainly goes to Vancouver. Launched in July 2016, the Mobi system is owned by the city and operated under contract with Cyclehop, which also operates systems in Atlanta and Southern California, among others. The municipal government invested Can$5 million in initial infrastructure costs, plus Can$1 million in other startup costs and committed to an annual Can$500,000 subsidy for the first five years. With about 1 million rides in the first year, the city has touted the system as a success.

Most electric-powered bicycles

With its abundance of thigh-busting hills, it makes sense that Seattle would win this category, too. Lime now rents more than 2,700 bikes that provide battery-powered assistance to pedaling, up to 15 mph. The e-bikes are spendier, at $5.50 for 30 minutes, but many riders walk past pedal-only bikes as they seek the e-bikes marked by a lightning-bolt symbol on the Lime app. Seattle’s dominance in this category likely will grow with the expected addition of Uber’s Jump, whose free-floating e-bikes differ from Lime in that they must be locked to a fixed object. Although not as convenient for riders, lock-to bikes can help to reduce roadside clutter, leading cities to make them mandatory.

Electricity appears to be the wave of the future. Bellevue, for example, has declared that the city will only admit vendors offering electric bikes. Portland’s BikeTown is without e-bikes at the moment but is looking into requiring them under the next operating contract in 2019, according to general manager Dorothy Mitchell.

Most Canadian

Although Kelowna’s system is operated by Canada-based Dropbike, it’s a relatively small pilot, so we’ll give this award to Victoria, BC, and its participating neighbors, Saanich, Esquimalt and Langford. Launched in 2017 and expanded to neighboring jurisdictions this year, the system is operated by British Columbia’s homegrown U-bicycle, whose self-locking bikes are meant to be returned to designated areas. Privately owned U-bicycle also is working to expand bike share in greater Vancouver, adding 100 bikes each in Port Moody and Port Coquitlam in August and 200 rolling out in Richmond in October.

Most electric scooters

Although no Cascadian city has so far formally approved ongoing scooter rentals, Portland conducted a boffo trial run with this latest urban mobility craze this summer and early fall. The four-month pilot allowed companies Bird, Lime and Skip to keep up to 2,500 scooters on Portland streets until Tuesday. As of early November, riders had taken more than 643,000 trips averaging 1.2 miles each for a total of more than 745,000 miles, according to the Portland Bureau of Transportation. As city officials whether to bring scooters back long-term early next year, one big question to assess will be the effect on BikeTown ridership.

In Seattle, meanwhile, Lime has urged local users to join a campaign to persuade Mayor Jenny Durkan to relent from her stance that scooters should be banned over safety worries. In a recent Seattle Times story, Gabriel Scheer, Lime’s director of strategic development, noted that cars kill more than 30,000 people a year in the US. “Scooters, bikes, e-bikes, we should be trying them all right now because we don’t have a lot of options that are going to continue to move through downtown,” Scheer said. “They will get through traffic when cars won’t.”

Rapid change, but is it permanent?

Although the delivery method is evolving quickly, bike share continues to come on strong in Cascadian cities, and there are good reasons to think such last-mile alternatives will stick around. Nicole Payne, program manager for bike share at National Association of City Transportation Officials, noted that the Pacific Northwest is characterized by tech-fueled growth and a desire to stave off climate change. Bike share—and potentially scooters and other “micro-mobility” options—will play an important role in addressing those challenges, she said.

“You can’t fill roads with cars as fast as people are moving in,” Payne added, “so you have to make space for all these other ways to get around. It will make cities think a lot more about designing for people walking and biking rather than just cars, it is really turning the conversation around.”

Comments are closed.