In less than two months, Cascadia’s largest city, Seattle, will close its Alaskan Way Viaduct once and for all. During the weeks it takes crews to connect its replacement deep bore tunnel, the city’s downtown traffic will endure a “period of maximum constraint.” Congestion could get nightmarish.

The truth is that ride-hailing services cannot compete with transit when it comes to sluicing thousands of people per hour, but they can complement transit by feeding it with riders and by substituting for expensive, low-ridership bus routes.

The Period of Maximum Constraint is also a golden opportunity. It’s a chance to demonstrate that a marriage between transit and ride-hailing services such as Uber and Lyft can solve the problems of each, easing congestion while improving service.

This marriage could be more than temporary. If it works during the PMC, it could become the new normal for an otherwise perilous relationship—a relationship that is growing increasingly fraught with arguments and distrust.

Consider: in June, the New York Times reported that anti-transit groups funded by the Koch brothers were killing transit projects across the United States; they have been arguing that ride-hailing services such as Uber and Lyft can substitute for buses and trains. It’s not true—as I’ll detail in this article—but it is an argument that inflames critics of ride-hailing and supporters of transit.

The truth is that ride-hailing services cannot compete with transit when it comes to sluicing thousands of people per hour through narrow corridors into and out of central cities, but they can complement transit by feeding it with riders and by substituting for expensive, low-ridership bus routes.

Can’t we all just get along?

A transit/ride-hailing marriage is far from inevitable. Ride-hailing companies, known as transportation network companies (TNCs), took more fire in July from a heavyweight in the transportation establishment. Bruce Schaller, a former senior transportation official with New York City, estimated that TNCs generate 2.8 miles of new driving for each mile of personal driving they replace. If that ratio is right, it would mean that TNCs added 94 million miles of additional road travel in Seattle in 2017. The Seattle Times reported in early November that Uber and Lyft carry 91,000 people per day in Seattle, more than the city’s light rail line.

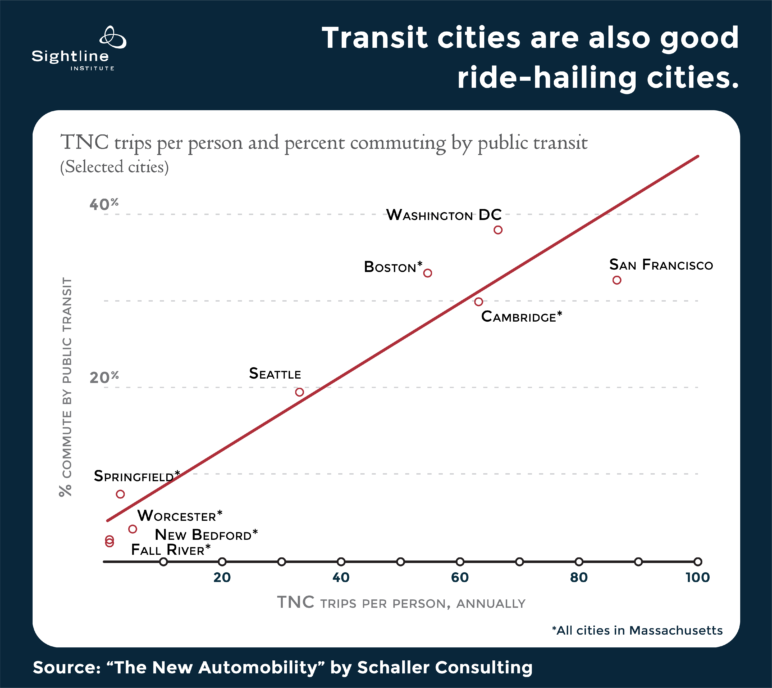

According to Schaller, Uber and Lyft are not primarily replacing private car trips. Instead, they are attracting passengers who otherwise would have walked, rode transit or just not gone. Schaller’s data in the graphic below show that cities’ transit ridership correlate with their TNC usage: cities that are good for transit are also good for TNCs. If public and private mobility services tend to thrive in the same markets, can we make them work well together?

Transit’s share of travel is declining in most US cities, so serious new competition for ridership could be an existential threat to fiscally stressed transit agencies. Ride-hailing services do indeed compete with transit because they outperform transit for certain trips—those not well served by transit, such as ones with lightly populated origins and lightly visited destinations. Intuitively, it seems like TNCs might even starve transit agencies of passengers and fare revenue. But such fears are exaggerated, at least in Cascadia’s cities.

For example, Seattle, unlike the rest of the United States, has seen transit ridership grow; commute trips to the central city on transit increased from 42 percent in 2010 to 48 percent in 2017. The fact that nearly half of the work trips to downtown Seattle are on high-capacity transit corridors debunks the Koch-funded notion that rideshare companies are a plausible substitute. You simply cannot fit that many passenger cars onto city streets during peak periods. A single 60-foot articulated bus can hold up to 90 people, with some standing. Even if TNC riders were to pool with three to a car, replacing just one articulated bus with TNC service could generate up to 30 additional vehicles on the same route. We need high-capacity transit corridors, mostly buses, into city centers because without them, city streets would clog to a standstill.

Using Uber and Lyft to Make Transit Better

As a first approximation, you can think of transit routes as either trunk lines or feeder lines. Trunk lines are transit’s sweet spot: buses and trains run full, fast, and cost-effectively. Feeder lines are not: vehicles run empty, slowly, and with massive financial losses. TNCs, again as a first approximation, are the opposite because they do best with three or fewer passengers in small vehicles on routes customized for each passenger. In other words, they are naturals for feeder lines, not trunk lines, where they get stuck in traffic.

Designing public policy so ride-hailing services strengthen public transit requires utilizing their complementary and competitive features. The commuting public would win if transit agencies focused on trunk lines and TNCs focused on feeder service, including “last mile” service connections from bus stop to destination and replacing buses on low-ridership routes that hemorrhage red ink.

Uber and Lyft have learned that to maintain political support for their business model, they need to cultivate the complementary character of their service for transit. The companies have made recent efforts to build transit alternatives into their apps, undertaken multiple pilots, and adopted public postures of support for strengthening last-mile connections to transit. Last year, for example, Uber ran a pilot with Sound Transit where the company offered discounts of $3.50 for riders it picked up or dropped off at eight stations on the southern end of greater Seattle’s Link Light Rail line. Lyft has a pilot underway with Pierce Transit, south of Seattle, to pick people up in zones with limited bus service and take them to transit stations. Lyft and Pierce Transit have designed the program to work for people without smartphones and those needing wheelchair assistance.

These pilots hold promise for increasing ridership and extending mobility to areas that now depend on private cars. The TNCs and transit agencies need to keep working on data sharing so both parties can better understand how the service influences transit ridership and overall trip making. Closer collaboration could reduce points of friction for riders as well as identifying revenue and payment models that work for all parties.

Using Uber and Lyft to Save Transit Money

For all the efficiency of a fully loaded bus moving into downtowns during the morning commute, the region’s bus transit system also must contend with the inefficiency of serving riders across low densities throughout the day. All you have to do to see big, near-empty buses, especially outside of rush hour, is to pay the scantest amount of attention. Coaches made to hold 40, 60, 80 or more people that instead hold three or five can be seen everywhere. Such bus trips carry exorbitant costs per trip, in public transit-agency dollars and in diesel-fuel emissions. In 2006, my Sightline colleague Clark Williams-Derry pointed out that a typical bus needs to carry at least ten passengers just to be better for carbon emissions than each of those passengers driving alone in average-efficiency cars.

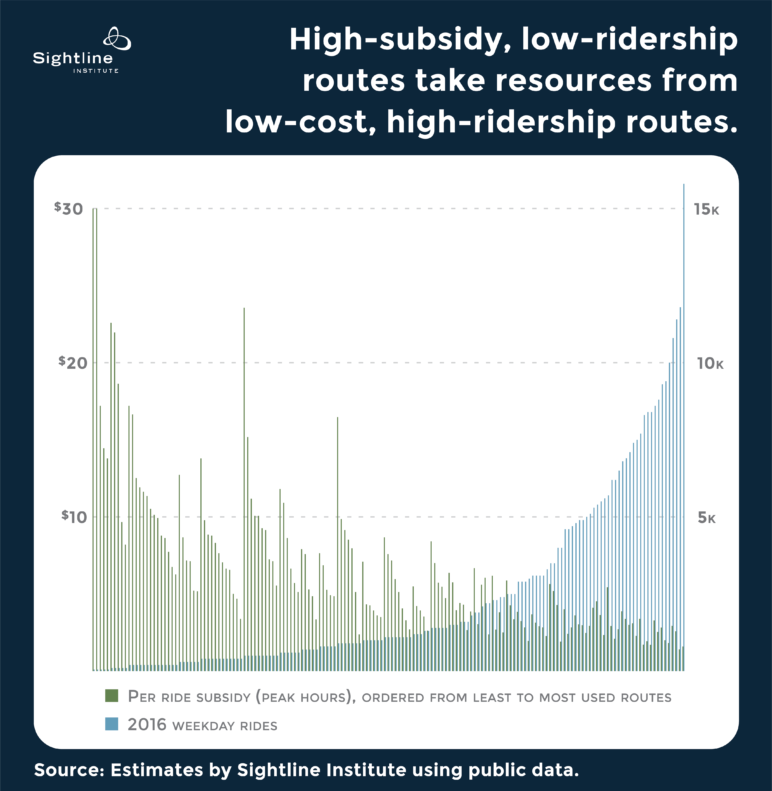

The chart below shows the daytime ridership for 165 King County Metro bus routes in blue. I arranged them from lowest to highest ridership. The “Rapid Ride E Line” at the far right of the chart carries over 15,000 passengers per day while Route 201 at the far left, which roams the south end of suburban Mercer Island, carries just 50 all day. The green lines show estimates of the per ride subsidy for the adjacent route ridership line in blue using Metro’s route productivity data and information from King County’s profile in the National Transportation Database. The per-trip subsidy ranges from over $30 per ride on the least productive routes on the left, such as Route 201, to less than $2 for the most productive routes on the right, such as the E Line.

(At this link, you’ll find my complete dataset, from which these figures derive. There, you can look up any Metro bus route you like and find how subsidized it is. But interpret the data with caution. I made a variety of simplifying assumptions to generate the figure, such as that each mile a bus is driven costs Metro the average amount reported to the National Transportation Database. The figures, therefore, are indicative rather than definitive.)

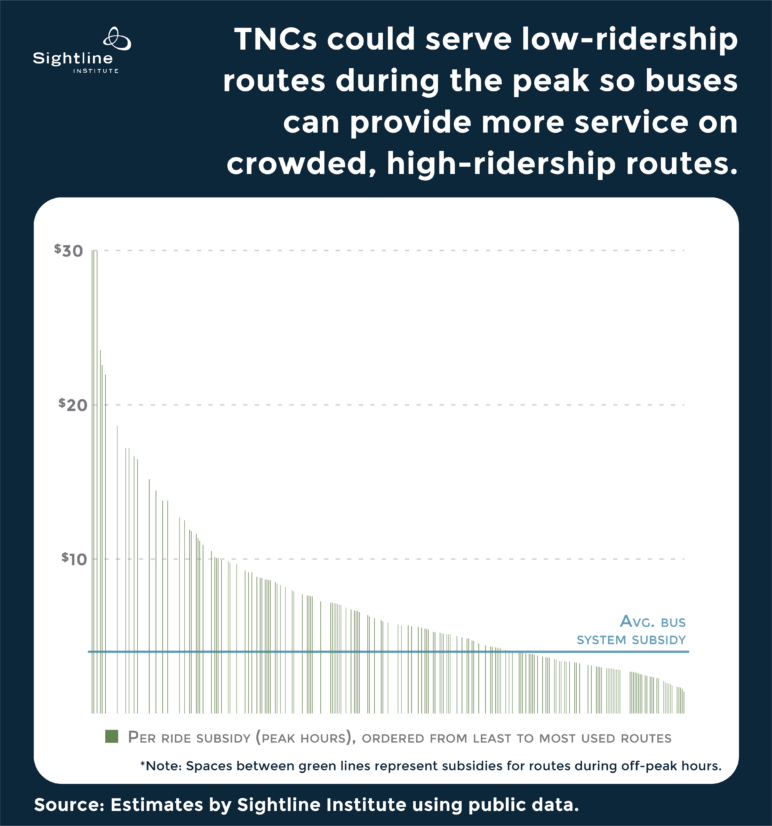

This next graphic shows the subsidy per rider during the rush hour or peak period only and is sorted from highest to lowest subsidy per trip. The average subsidy per trip, shown by the solid blue line, is $4. More than half of ridership during rush hour is on the highly productive routes that are on the far right of the graph, where per-rider subsidies are less than $4. This graph suggests another opportunity for TNCs to improve transit systems. What if transit agencies contracted with TNCs to provide service on low-productivity routes on the left and used the savings to improve service for the high productivity routes on the right?

In Seattle in recent years, buses on the busiest routes have been crowded not only to the point of standing-room only but to the point where drivers are leaving passengers on the curb for lack of space to put them. In April, Metro told the City of Seattle it was unable to add buses during the peak period, despite the crowding, and even though the city offered to pay for the extra bus trips. Metro’s reason was that it cannot find drivers fast enough and that it lacks the overnight storage space for more buses in the near term. Remember now that even during the peak periods, Metro is running buses with few passengers aboard—few enough that the rate of subsidy rises to $30 per ride. These nearly empty buses, of course, have drivers and room at the bus barn for the night.

What if, working with the TNCs, Metro shifted drivers and buses from its near-empty routes (on the left of the figure) to increase the frequency of service on the high productivity routes (on the right of the figure)? If you took the least productive bus routes that average subsidies of $14 trip, such as Route 201, and replaced them with a TNC pooling service at $10 per trip, you could put $4 per trip into adding bus service where the system needs it most. Happily, this doesn’t pit Uber drivers against bus drivers. All the bus drivers keep their jobs. Some would just shift from driving empty buses to driving full ones. TNC drivers would have a new market for their services and the public would get more transit service for the same expenditures.

To their credit, Seattle and King County Metro have studied the possibility of TNCs substituting for buses and identified five routes as potential candidates. The advent of pooling services from Uber and Lyft and my research indicate that Uber and Lyft could cost-effectively service many more, but these five are a good place to start. Metro has stated: “New and innovative mobility services can complement transit by offering riders first- and last-mile connections to and from transit and by creating cost-effective ways to serve low-density areas. The integration of these emerging services with transit can transform regional mobility.”

Metro has a near-term opportunity to turn these lofty policy goals into action.

Don’t Let a Serious Crisis Go to Waste: Traffic Apocalypse Arrives January 2019

On January 11, 2019, Washington’s Highway 99 on the Alaska Way Viaduct will close for at least three weeks to connect the newly constructed tunnel to the existing roadway. About 91,000 vehicles per day use the south end of the viaduct. Washington Department of Transportation has issued a call on its website for employers and travelers to “start making plans” for the closure, which of course includes “use transit.” But buses that are already crowded are unlikely to attract vast new numbers of riders without adding capacity to already crowded routes.

What if, for the three weeks of the viaduct closure, Metro shifted bus service from low-ridership routes to high demand routes to help mitigate congestion downtown? For those three weeks, Uber, Lyft, ReachNow, taxis and other services would connect passengers on low-ridership routes to high-capacity lines and thereby free up buses to better serve congested routes into downtown Seattle. This emergency pilot program could test a number of program design ideas and generate useful data for a carefully considered program that would develop along normal transit planning timelines. As Rahm Emanuel said, “You never want a serious crisis to go to waste.”

The Evolution of Urban Mobility

Using ridesharing service to substitute for bus routes requires the companies and transit agencies to approach their business in new ways. The TNCs would have to get better at sharing data so city and transit planners could track chained trips on and off public transit to evaluate how much of their ridership uses a TNC. The companies also need to take steps to better integrate payment and hailing technologies. Not every bus rider has a smartphone so TNCs will want to build on services like Uber Central and Lyft’s Pierce Transit program. In Seattle, Metro could develop a system that would send a vehicle to a location hailed by phone or text message and allow for payment with an Orca card.

By thinking holistically about how transit and shared mobility services can work together, policymakers can deliver better environmental and economic outcomes for public transit dollars. Cascadia’s clean transportation future requires cost-effective, high-capacity public transit corridors with a complement of shared mobility services that use cars, bikes, e-scooters, and eventually electric robo-taxis to make smart connections. By demonstrating how public transit and private mobility services can work together, Cascadia will move toward a less congested, low-carbon future and help limit the misinformation and petroleum peddled by the Koch brothers.

Comments are closed.