Although Alberta is not in Cascadia, the decisions made there have a disproportionate impact on the lives of West Coast Canadians and Americans. Besides being home to the largest oil sands mines in the world—with a correspondingly high contribution to greenhouse gas emissions—Alberta is also the origin of the existing Trans Mountain pipeline, and the Albertan government is fighting hard to ensure construction of the newer, bigger Trans Mountain twin that is so strongly opposed by communities throughout the Salish Sea and along the pipeline route in British Columbia.

Alberta is the eighth-largest producer of oil and natural gas in the world and is responsible for an impressive 80 percent of Canada’s total crude oil production. The province is also Canada’s largest greenhouse gas emitter—and the most polarized when it comes to opinions on climate change.

There is a desperate need for a constructive dialogue about energy, climate change, and the province’s future, yet most Albertans rarely discuss these issues. This is why a coalition of nonprofits, foundations, and research institutions came together to produce the Alberta Narratives Project: “a community-based initiative to seek ways of talking about climate and energy that reflect the shared values and identities of Albertans and to provide a more open and constructive basis for conversation.”

Although fossil fuels are a pillar of the economy, Albertans across political ideologies tend to be proud of the province’s environmental regulations—the oil and gas industry is seen as a leader in technological advances to reduce the sector’s environmental footprint. There’s also a strong shared belief that much of Alberta’s prosperity is in thanks to oil and gas. It is especially important to find ways to talk about climate and energy issues without implying blame or shaming those who are connected to the industry.

Despite their pride in Alberta’s abundant wilderness and outdoor recreation opportunities, polling shows Albertans report a far lower level of concern about climate change than the rest of Canada. In keeping with their American counterparts, conservatives especially have a tendency to downplay or deny the issue.

So, what can we learn from Alberta about how to talk about climate and energy in a way that reduces polarization, rather than crystalizes it? That opens people up to possibilities, rather than alienating or insulting them? Using Climate Outreach’s peer-reviewed Narrative Workshop methodology and enlisting a range of community partners, the project hosted 55 narrative workshops across Alberta over the course of 2018.

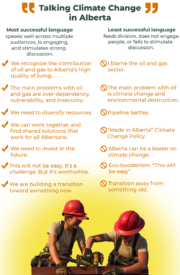

Through an intensive facilitated dialogue with more than 480 Albertans from all walks of life, the team of social scientists and communications specialists developed a core narrative to spark public engagement as well as an extensive guidebook for climate communicators. The report identifies approaches that are common sense for any type of communication—building language around values and identities, finding common values from the outset, finding a trusted messenger, and avoiding absolutes—as well as a number of key finding specific to Albertans’ diversity of values and identities.

Here are some of the most important things to keep in mind:

Recognize the contribution of oil and gas to Alberta’s high quality of living.

To initiate a positive conversation, communicators should reflect on the connection that many Albertans have with the oil and gas industry and recognize the contribution that those working in the industry have made to their prosperity and way of life.

The main problems with oil and gas are over-dependency, vulnerability, and insecurity.

People’s primary concern is that the provincial economy—and their livelihoods— are tied to a volatile global demand and oil prices. This boom and bust cycle, external criticism, and the tightening of national and international climate change policy generate insecurity and uncertainty.

We need to diversify; we can’t solely count on fossil fuels.

There is a strong interest in building a broader economic base and supporting new growth sectors, including renewables.

We can work together and find shared solutions that work for all of us.

People responded most positively to cooperative language rather than combative language. The experience in many jurisdictions (including British Columbia, California, Germany, and the United Kingdom) is that building a cross-party consensus, based on shared values, has been essential for building lasting policy.

We need to invest in the future.

Study participants were widely concerned about the long-term implications of investment decisions, especially in infrastructure. They questioned the cost of pipelines, whether they could pay back their high-capital costs and the lack of investment in oil refining. A discussion about the choices of where to make long-term investment decisions would initiate a broad and open discussion.

This will not be easy—but we’re up to the challenge and it’ll be worth it.

People in Alberta are proud of their ability to respond, adapt and cope. Study participants strongly favored language that responded to climate change by saying an energy transition will “not be easy” and will be “challenging” but, through that process, it could be rewarding. This language was seen as authentic and honest.

We are building a transition toward something new.

People are proud to see Albertans as “builders.” A transition to new energy sources can be presented as building new infrastructure toward a positive objective (clean energy, diversified economy, new opportunities). A transition should also be a move toward a diversified economy with increased growth outside of the energy sector.

Comments are closed.