Streets are what make a city a city. It’s not the buildings themselves, but the chance to move among and between them, that creates the joys and economic blessings of city life.

Of course, those joys and blessings make city life popular—and the popularity of moving between a city’s buildings causes one of the main challenges of city life: traffic.

That’s why it’s so exciting when a Cascadian city comes up with a plan that would actually make its streets work better, permanently.

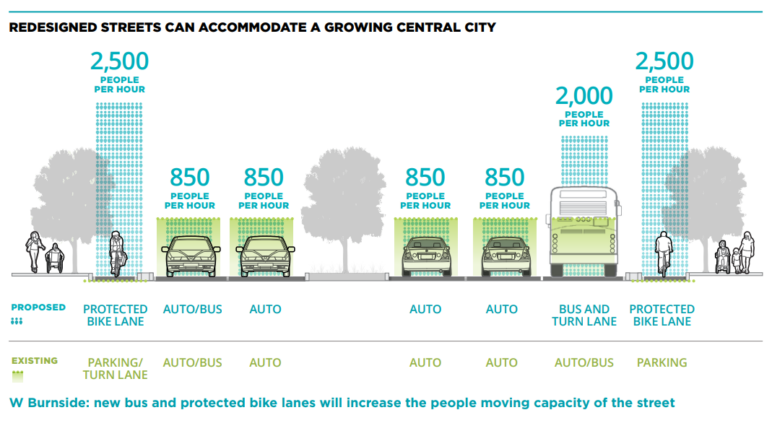

The proposal going before Portland City Council Thursday afternoon avoids the false promise of bigger roads: 39 percent of the central city is already dedicated to street space, it notes. So, instead, it’s planning to dedicate an additional 1 percent of those central streets to bike lanes and another 1 percent to bus lanes.

That little shift in urban space, which would take the form of 18 street projects over the next 10 years, would boost the people-moving capacity of the affected streets by an average of 60 percent.

That’s based on calculations from the National Association of City Transportation Officials. It’d be the city’s most important bus infrastructure investment in 40 years, and its most important biking infrastructure investment in 20.

Price tag: $72 million, or about the cost of a single mile of urban freeway.

It’s worth noting that boosting the potential capacity of a street isn’t the same as getting people to use that potential by riding a bike or getting on a bus. And one potential risk of Portland’s current plan is that a big part of it—a connected lattice of low-stress bike lanes throughout central Portland—might not pay off much until the entire network is finished.

Just like a road network or a computer network, low-stress bikeways have little value to anyone until they’re connected to other low-stress bikeways.

Some cities—Vancouver, BC; Calgary, Alberta; Sevilla, Spain—have recently shown the power of installing a simple protected bike lane network all at once, with relatively cheap and adjustable materials, so transportation habits can shift quickly and everyone—voters, nearby businesses, politicians themselves—can see the payoff. It’s not clear whether or not Portland is planning to learn from that example as it builds its own network.

That said, the only way a city can truly fight traffic is to better use the street space that already exists. If Portland moves this plan forward, it’ll become the latest city to show the rest of the world how to fight congestion right, letting more people enjoy the promise and joys of the city.

Comments are closed.