The United States and Canada haven’t upgraded their democratic systems in centuries, leading to some of the most unrepresentative legislative bodies and disenfranchised voters across the globe’s democracies. We can fix this by spreading the use of upgraded voting systems such as proportional representation, including multi-winner districts and ranked-choice voting. These improved systems are already in use in cities and states in the United States and in most successful democracies around the world.

If US states replaced their single-winner districts with multi-winner proportional districts, elected representatives would mirror the political composition in their state. This more accurate balance would force lawmakers to be more accountable to voters instead of special interests. They could no longer afford to ignore voters in the minority or in safe districts. Here are just a handful of ways that electoral system upgrades, specifically proportional representation (ProRep), deliver better, more democratic results.

1. Proportional representation makes everyone’s vote matter.

Winner-take-all voting systems, like the ones we use in Canada and the United States, often leave half or more voters with no voice. With 51 percent of the vote (or less) a winner takes all the control in that district. Repeated across districts, one party can take control of the legislature. Proportional systems, by contrast, mean the number of seats reflects the proportion of votes. Twenty percent of the vote means 20 percent of the seats; 40 percent means 40 percent. ProRep ensures almost all voters—even those who support a minority party—can elect someone they like. Proportional systems give almost all voters an advocate at the policy table.

In proportional systems, one winner doesn’t take control, but rather power is divided based on the share of votes each party receives. A minority of votes doesn’t mean total lock-out. Above a minimum threshold, it means a minority share of seats—but still seats at the table! This makes every vote matter. When everyone’s vote counts, candidates can’t take voters in the minority for granted.

2. Proportional representation empowers women and people of color.

Proportional representation has a history of putting more women in office. In countries that use proportional representation, women are almost twice as likely to get elected to office compared to winner-take-all systems. In a comparative study of 36 countries, the share of women elected to the legislature was 8 percentage points higher in proportional representation countries. All the ProRep countries in Western Europe have at least 20 percent women in parliament.

And multi-winner districts with seats elected proportionally would mean that any group in the minority, no matter where they live within the district, would have a good chance of electing someone to represent them. For example, if Green Party voters comprise 20 percent of the vote, they could elect at least one of the five seats. Same for African-American voters, if they tend to vote together. More-proportional voting systems in hundreds of cities across the US have the election results to prove that electoral system reform is a more robust solution to the problem of underrepresentation of people of color than redistricting in single-winner districts.

3. Proportional representation delivers stronger environmental protections.

No electoral system can guarantee certain outcomes, but the record shows that ProRep countries have stronger environmental protections. One reason: With ProRep, voters have more influence. When voters matter, the system has to be more responsive to the people than to moneyed interests. ProRep countries were quicker to ratify the Kyoto Protocol and have slowed their carbon dioxide emissions more than four times as quickly as winner-take-all countries. ProRep countries are more likely to have Green Party representation in their legislatures, too. Once they win seats, Green candidates can introduce innovative policy ideas, some of which steadily work their way into the mainstream. Often, Greens make coalition partners for bigger parties, helping set a pro-environment agenda.

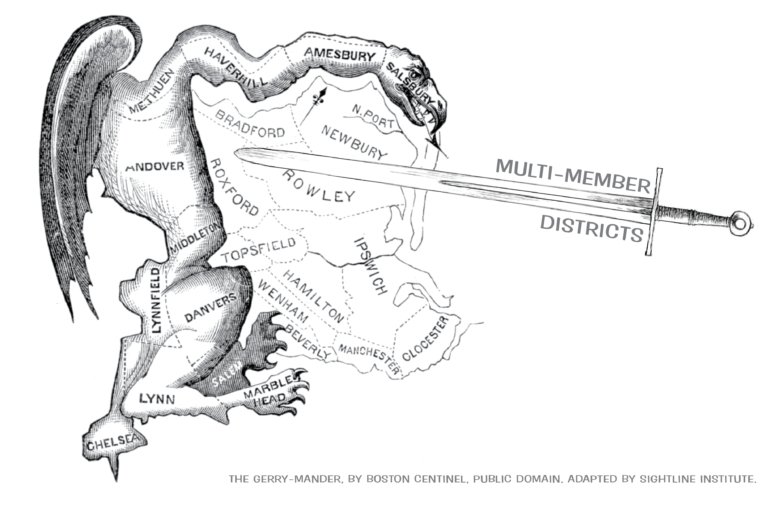

4. Proportional representation defangs gerrymandering.

A supermajority of Americans wants the Supreme Court to rein in partisan gerrymandering, including 80 percent of Democrats, 68 percent of Independents and 65 percent of Republicans. Replacing single-winner districts with larger, multi-winner districts and proportional voting would largely bypass the gerrymandering mess. That switch would eliminate safe seats, diminish the power of cracking and packing, and render partisan redistricting battles irrelevant. It is difficult or impossible to gerrymander the lines in proportional districts.

With winner-take-all districts, whoever holds the pen can draw districts based on party preferences. Even algorithms and independent commissions have trouble drawing fair lines. But when voters belong to much bigger districts and elect multiple candidates, one winner can’t take all the power. Instead, multiple candidates represent each district according to how many votes each gets. Even if 80 percent of voters in a district favor one party, the 20 percent minority electorate isn’t shut out—they still keep 20 percent of the power. No matter how the district lines are drawn and no matter how party voters are distributed among districts, almost all voters have a say in sending representatives they prefer to office.

5. Proportional representation makes politicians more responsive and accountable to voters.

When voters pick their politicians instead of politicians picking their voters (see: gerrymandering, above), representatives have to be more accountable to the people. When seats are based on the share of votes, politicians are more cooperative and more accountable to their constituents.

In multi-winner systems where seats are proportional to votes, even small shifts in voter preferences can shift the share of seats. Races are always competitive. Voters’ preferences always matter. And, when their votes matter, more voters check in instead of checking out. More people turn out to vote in ProRep countries than winner-take-all countries. When more voters participate, leaders are motivated to become more responsive to everyone in their district, not just their base.

6. Proportional representation boosts economic equality and empowers low-income voters.

Countries that use proportional representation (ProRep) have less inequality and more equality-enhancing policies compared with winner-take-all countries such as Canada and the US. Because candidates in winner-take-all countries only have to answer to certain voters, they are more likely to protect the wealthy at the expense of lower-income people. A recent analysis of 24 democracies found that proportional electoral rule reduces underrepresentation of the poor. Representatives in ProRep countries reflect a broader swath of society and the record shows they spend more on public education, health care, and other policies that reduce inequality. Overall, ProRep countries are more economically equal than winner-take-all countries.

7. Proportional representation breaks two-party dominance.

Political scientists have known for nearly a century that plurality voting in single-winner districts leads to two-party domination. Two-party dominance leads to see-sawing between opposing sides, each of which might gain power in any given year with a minority of votes. Voters for the losing side (even if their side actually won more votes) feel locked out of government until the next election. Polarization and bitter partisanship are one result.

Despite the fact that more Americans identify as independent than Democrat or Republican, almost all American legislators are elected under the Democrat or Republican banner. Canada’s parliamentary system lends to more diversity than America’s system, but even so, two major parties still dominate and smaller parties suffer, as a direct result of winner-take-all ridings. In 2015, more than3 percent of Canadian voters voted for the Green Party, but the party won just 0.3 percent of seats in Parliament. The New Democratic Party won 20 percent of the vote but only 13 percent of seats.

Legislatures in proportional systems end up with more parties, better representing a broader range of voter viewpoints. For example, in Ireland, voters who believe in “People before Profit” have six legislators representing them, independents have four legislators. In Australia, the Greens have nine representatives in the Senate.

More diverse viewpoints and robust third parties foster innovative solutions. More parties competing for votes brings new ideas to political debates. Many ProRep countries adopted marriage equality faster than winner-take-all countries because smaller parties brought the then-radical idea into campaigns and political discussions. The idea worked its way into the mainstream. In the US, neither of the two major parties wanted to risk adopting a radical view, so it took much longer for Congress to take the topic seriously. More parties working together also creates more durably popular policies. Lawmakers have to consider many views instead of just steamrolling whichever party is not in power at the moment, then rolling back once the other party comes to power.

8. Proportional representation loosens Big Money’s grip on parties and policymaking.

Most—93 percent—of American voters surveyed in a 2016 poll said they believe elected officials listen more to wealthy donors than regular voters. Majorities want to limit campaign contributions and get rid of Citizens United. When voters have more power to decide who gets into office and results are proportional, big money has less leverage over candidates. Proportional countries have greater success in adopting policies opposed by powerful economic interests.

With more parties, voters discontented with one party can turn to another. Candidates need less money to campaign for a share of votes than they do for single-winner races, so money isn’t as powerful a factor in choosing winners and losers. Plus, lawmakers in proportional governments have to work together to build majorities to pass policies, meaning they can’t simply attack and tear down other lawmakers; they aren’t beholden to the Big Money fueling TV attack ads. Candidates and campaigns are motivated to focus more on issues—and longer-term solutions. When money is less decisive in a campaign, it is also less decisive in who moves up through leadership positions. Lawmakers can focus on being good at their jobs instead of being good at dialing for dollars.

Comments are closed.