For housing advocates, could there be a better way?

As urban housing shortages drive poor people out of job-rich cities, as middle-class families risk their life savings on exurban tract housing because it’s what they can afford, and as the planet keeps ticking toward deeper climate-driven disasters, is there some path to fair, abundant, transit-friendly housing that doesn’t require battling the forces of stasis up an endless staircase of 2 p.m. hearings at City Hall?

Last year in California, a pair of state senators threw up a new idea for how to escape the hand-to-hand warfare currently required to make it legal for more people to live in cities: a higher level of government could intervene.

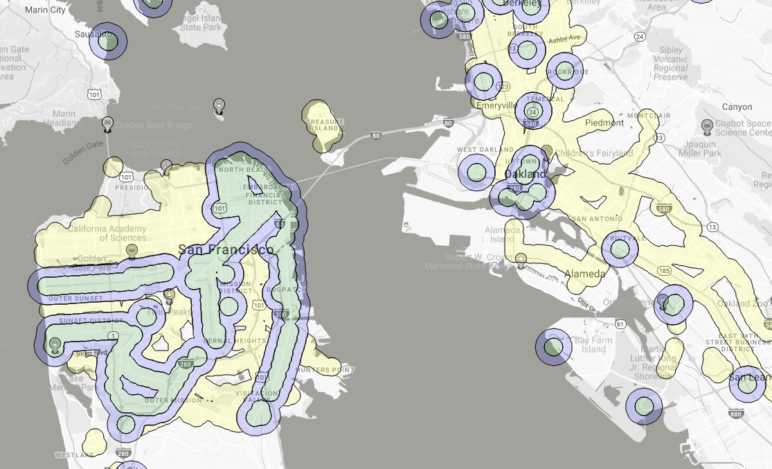

The final version of their conversation-starting bill, SB 827, would have blocked California’s cities and counties from banning housing of less than five stories within a quarter-mile of any bus stop with relatively frequent service, or four stories within a half-mile of any major transit station.

That bill died in committee in April. (A somewhat similar bill passed the Connecticut House of Representatives the following week, but awaits Senate action.) But as a Washington state senator circulates an apartment-legalization bill of his own and Oregonians quietly discuss the same possibility, we at Sightline wanted to know if a game-changing state bill to override local obstacles to housing could happen in the Pacific Northwest.

We also wanted to know if something like it already had—and what lessons Cascadia could draw from past efforts to make transit-rich housing legal.

Here’s what I’ve learned so far.

How British Columbia got its cities to want people

One thing about the transit-oriented housing in greater Vancouver is unquestionable: It is spectacular.

The big streets through most of Vancouver and its suburbs were created in the same postwar boom that built most of Cascadia’s urban areas, and much of metro Vancouver remains just as auto-oriented as suburban Seattle.

Just like elsewhere, retailers are forced to bear the cost of parking for customers who drive. Just like elsewhere, low-density residential neighborhoods stretch for miles (even though most of them also include basement suites and backyard cottages).

But around the transit stations, steel and concrete towers spike skyward.

These towers didn’t just happen. But—and this may be the crucial lesson British Columbia has to offer—they weren’t mandated, either.

British Columbia, inarguably one of North America’s most successful models for modern transit-oriented development, has never forced upzones near transit. Instead, it did two things, which worked at least in part by accident: it indirectly forced local action by blocking urban sprawl, and it gave its cities concrete incentives to work together.

Upzone lesson No. 1: Force a regional conversation by constraining sprawl

Vancouver’s suburban towers sprang from a decades-long negotiation among the region’s cities. The province’s first New Democratic government had forced the conversation when it created a de facto provincial sprawl boundary in the form of the 1973 Agricultural Land Reserve.

Before that law, a city like Burnaby, immediately east of Vancouver proper and packed mostly with detached homes, had generally assumed that it was “fully developed” and wouldn’t need to accommodate more residents.

“They thought they were all done,” said Ken Cameron, former strategic planner for the Metro Vancouver Regional District and author of City Making in Paradise: Nine Decisions that Saved Greater Vancouver’s Livability.

But the agricultural reserve forced cities to think again. They did so in a series of planning efforts convened by the suddenly influential MVRD, a body whose predecessor had been created decades before to coordinate water and sewer service.

“Through this process there was sort of a dialogue that created: if these people are not going to be accomodated in redevelopment in Burnaby, then they’re going to need to be accomodated somewhere else,” Cameron said. “These people may not be living here, but they’re going to be driving through here. What do you want?”

Upzone lesson No. 2: Give cities reasons to want housing growth

Any regional government can talk through its problems and agree on theoretical solutions: 2,000 new homes for Coquitlam, 3,000 for Richmond. But why should those constituent cities—and, crucially, their voters—listen?

It’s a question with new importance after a surge of anti-housing candidates in British Columbia’s most recent local elections.

If cities retain the authority to prevent significant changes to local buildings and watch as the resulting housing scarcity drives home values ever upward, then who cares what the Metro Vancouver Regional District says?

“It’s a relatively toothless body,” said Brendan Hurley, an urban design planner for the city of North Vancouver and a former planner in Burnaby, Seattle and elsewhere. “Except for [two] key pieces, which are water and sewage.”

Hurley argues that even if MVRD never actually used its control of regional water and sewer capacity to force a city to follow its planning commitments, the mere presence of that threat is enough to give weight to MVRD negotiations.

“The reality of cities is waste and water; everything else is just dressing,” Hurley said. “If those are taken away, the city doesn’t exist. … The thing I would recommend highly for any US group is that if you make a regional government, they control water.”

Hurley may have a point. The only regional authority in the United States that combines land use, transportation planning and sewer service is also one of the strongest: the Metro Council of greater Minneapolis.

Cameron, the MVRD planner, offers a more familiar theory: money. Because Vancouver’s cities are funded almost entirely by property taxes, which are relatively flat per household, he said they have a fiscal incentive to add households.

That makes British Columbia unlike California, for example, where tightly capped property taxes make employment land vastly more attractive for a city than residential land; or Washington, where high municipal sales taxes give cities an incentive to attract retail, but not to house low-income people.

“Residential growth is not seen by municipalities, by local governments in this region, as a burden at any income level,” Cameron said. “They don’t plan their cities in a way to have higher-income households and avoid the lower-income households.”

If Cameron is right, British Columbia’s system of funding cities mostly with property taxes echoes a much stronger local growth incentive in Germany. There, an equalization grants system redistributes a share of tax revenue on a per-person basis—giving every German city a very concrete fiscal reward for adding population. As my colleague Alan Durning wrote last year, home prices in Europe’s cornerstone economy are low, “more like Houston than San Francisco or London,” thanks in large part to localities that consistently allow housing construction.

Hurley and Cameron offer interesting, informed speculations about why British Columbia has been so good at dividing its pie. They may or may not be right. Maybe Canadian culture is just suited to regional collaboration. Or maybe it’s actually unsurprising for a region whose residents are 29 percent first-generation immigrants from Asia to deliberately build cities that look more like Asian ones.

In any case, there’s an important thing British Columbia can’t brag about: making its pie bigger quickly enough.

Upzoning lesson No. 3: It’s nice to share the costs of change, but you also have to build enough

We’ve established that suburban Vancouver’s transit-oriented towers are spectacular, and that they’re admirably well-distributed. The trouble is that they’re insufficient.

“Burnaby has these massively tall town centers and these completely protected single-family districts,” Hurley said. “Towers aren’t intrinsically good, and in some ways we’ve been able to create them as cul-de-sacs in the sky.”

Because buildings of eight stories or more are almost twice as expensive to build per square foot as attached wood-frame homes, they’d be unlikely to exist at all if they had to compete with abundant low-rise housing nearby. But they don’t, because low-rise apartment buildings have been banned from most of the suburbs.

Accessory dwellings, at least, are now legal in most Vancouver suburbs. But loosening rules for them could get more built.

“Adding a secondary suite to every fifth house would do more than the towers,” Hurley said.

There is no question that something is very wrong with Greater Vancouver’s housing market. Its rental housing vacancy rate was 0.9 percent in 2017 and hasn’t broken 3 percent in at least 25 years. (Anything below 5 percent vacancy is generally considered unhealthy.) One in five BC renters spends more than half their income on housing.The median home in metro Vancouver costs about 12 times what the median metro-Vancouver household earns. That’s the third-worst ratio among world cities tracked by one annual survey.

Legalizing low-rise apartments throughout Greater Vancouver might solve that. But unlike low-rise apartments, high-rise transit nodes have the crucial virtue of being legal. If not for regional negotiation, they might never have existed.

“My view is that it would have been worse if we hadn’t had a plan,” Cameron said.

That’s also the view from Guy Akester, director of real estate programs and partnerships for TransLink, the regional transit agency.

“If we didn’t have this cooperative relationship with our municipal partners, the taxpayer would be paying a big price for transit service to serve a widespread region of low-density, single-family housing,” Akester told BC Business in 2016.

In British Columbia, provincial legislation probably helped force local negotiation, but negotiations mean compromise. If the terms of that compromise were that suburbs would accept growth if and only if it came in the form of intense transit-oriented density, maybe that’s the best British Columbians can ever hope for.

Or maybe not. Let’s consider some lessons from farther south.

Washington shows two ways state-led action can flop

Cascadia’s most populous jurisdiction has toyed for many years with the idea of taming local exclusionary zoning with state action.

For the most part, it hasn’t worked. But two of its failures—one in 1993, and one in 2009—may teach us at least as much as any jurisdiction’s successes.

Upzoning lesson No. 4: If cities can find a way to defy a state upzone, they probably will

Washington has passed exactly one state law mandating housing legalization in any specific way.

That’s one more law than British Columbia has ever passed.

Senate Bill 5584 sailed through Washington’s statehouse in 1993 with overwhelming margins. It was called the Washington Housing Policy Act, and one of its many provisions required every Washington city of 20,000 or more to legalize on-site cottages.

Accessory dwelling units—sometimes called mother-in-law apartments—had existed for centuries, of course. But the gradual spread of exclusionary zoning had made new ones illegal for much of the 20th century. In 1993, Washington’s legislature officially re-legalized them.

And then, for years, almost nothing happened. As my colleague Margaret Morales explained in May, Bellingham duly legalized ADUs in 1995 … and proceeded to allow an average of just four per year for the next 22 years.

The story was similar in most Washington cities. ADUs were legal, yes. But ensuring that few would ever be built was as simple as requiring, for example, one parking space for every new bedroom (which is exactly what Bellingham once required).

Washington’s legislature had led its cities to water, but it couldn’t make them drink.

It took decades for this to change. When it did, it was because pressure to actually encourage ADUs, rather than merely legalizing them, had showed up in city halls like Bellingham’s. As in British Columbia, it had taken local incentives, not state mandates, to actually create housing. Cities uninterested in adding homes had too many options for blocking them.

Upzoning lesson No. 5: Some homeowners will and can mobilize resistance, regardless of the facts of the proposal

In 2009, Washington came close to something big.

In its original form, House Bill 1490 would have done the following within a half-mile of every rail transit station (not counting streetcars) and high-quality bus rapid transit line in the state:

- Required cities to allow an average of at least 50 homes per acre—mostly three- to four-story buildings, in other words.

- Set some of the nation’s most stringent inclusionary zoning requirements: 25 percent of new units affordable to households making at most 80 percent of county median income, of which two-fifths would be affordable to households making at most 60 percent of county median income. (All of these dwellings would have been bonus units allowed above the zoned density, but the legislation provided no public support to offset their cost, so this rule would have almost certainly reduced total housing construction near Seattle’s rail stations.)

- If buildings were being demolished, required no net on-site loss of homes affordable to households making less than 80 percent of county median income.

- Mandated developer-funded relocation assistance for any low-income households displaced by development.

- Made on-site parking spaces optional.

It was, in other words, quite similar to California’s Senate Bill 827 from nine years later, though slanted toward price regulation more than housing production. But HB 1490, which was backed by anti-sprawl group Futurewise and the Washington Low-Income Housing Alliance, didn’t end there: it would have also required larger cities and counties to consider the long-term climate impact of all their land-use plans, including urban growth boundary expansions.

A freakout followed.

Seattle Met, Sightline, the Stranger and Seattle Transit Blog covered the bill favorably. In a statement now lost to the Internet, the Seattle Displacement Coalition came out swinging against it, after apparently misinterpreting its text as requiring minimum densities four times greater than it actually did. Meanwhile, some owners of detached homes near rail stations objected loudly to any state attempt to legalize apartments near them. Seattle City Councilor Sally Clark told the Seattle Times she’d “heard concerns at nearly every community meeting she’s attended in recent weeks.” Seattle Mayor Greg Nickels, locked into a doomed reelection campaign, came out against the bill despite a career of support for housing and mass transit.

The pressure was too much. Sponsors gutted specific upzoning requirements from the bill, leaving only the general requirement to zone for compliance with state and federal greenhouse-gas targets and to ensure “an adequate supply of housing that is affordable to low and moderate-income households” within a half-mile of rail.

Essentially, the revised bill left it to administrative officials and state courts to arbitrate what the specific requirements would be.

This revised bill was still opposed by “developers, Republican lawmakers and some Seattle residents,” but supporters claimed it now had the votes to pass. In a late effort to keep it off the floor before a crucial legislative deadline, House Republicans attempted to “paper” it to death by introducing a series of time-consuming amendments. It worked. The bill died despite two committee endorsements.

Like California’s SB 827 after it, the hard homes-per-acre mandate in Washington’s HB 1490 had been killed by some combination of homeowner backlash and disagreement among advocates for low-income housing. Then, the less specific version of the bill was killed by a lack of enthusiasm to prioritize it.

Upzoning lesson No. 6: Even a state action that mostly fails can lead to gradual change

Washington’s two attempts at state-led upzoning show two different ways that legislation can fail to deliver quick change.

In 1993’s ADU legalization, Washington housing advocates learned that even when state law gets fairly specific, cities can find ways to evade the spirit of a law. In 2009’s transit-oriented development bill, they learned that an even more specific proposal will tend to attract controversy because its effects are relatively concrete and easy to understand.

But the 1993 ADU legalization may also show a way legislation can deliver slow change. As I mentioned, the law only netted Bellingham four ADUs per year. But that’s four more ADUs per year than the city was permitting before that. And good ideas are contagious.

In a city where housing is scarce, a dozen ADUs can beget an ADU home tour, which can beget an advocacy network, which can beget ever-louder word of mouth. Eventually, this is how we get grassroots pressure for city-led reform.

What if Washington had passed the revised, less specific version of its transit-oriented development bill? Would that have opened a crack in the invisible walls that lock apartment buildings out of suburban rail stops like Mercer Island’s? Would the resulting development have become a good idea that gradually spread? Or would the law have become an empty gesture, ignored and unenforced?

If Washington’s 2009 law had passed, the results might have looked something like what Oregon saw in the wake of passing Cascadia’s only truly successful state-led upzone, to date: Senate Bill 100, in 1973.

How Oregon passed the state-led upzone no one knows about

Many people know that Oregon has passed a law to limit sprawl into farmland, like Washington and British Columbia.

It’s less well-known that Oregon’s anti-sprawl law, unlike Washington’s or British Columbia’s, also triggered a mass upzone that doubled the maximum housing capacity of the Portland metro area over four years from 1978 to 1982.

Over the same period, Oregon’s Senate Bill 100 also tripled the share of buildable land in Oregon zoned for multifamily housing, from 8 percent to 27 percent.

Why isn’t this upzone more famous? Maybe because it hid behind Upzoning Lesson #7.

Upzoning lesson No. 7: Sometimes it works to legislate generalities, then hash out details with administration and legislation

SB 100 was signed in May 1973, just 42 days after British Columbia’s Agricultural Land Reserve had taken effect and 17 years before Washington followed suit with its own law.

But the text of Oregon’s law could hardly have been vaguer: it said only that local land-use plans must “assure sound housing” for Oregonians.

It was the only mention of housing in the bill. But the officials appointed to interpret those words concluded, accurately, that if you’re going to make sprawl illegal, you’re going to make life worse for a lot of people unless you also legalize infill.

That was the origin of a state rule that required “allowance for a variety of densities and types of residences in each community.”

As a result of this rule, no Oregon city of significant size is allowed to forbid attached housing, in theory or in practice.

Within the Portland metro area, state regulators concluded, special standards were needed. All but the smallest cities were newly required to “designate sufficient buildable land to provide the opportunity for at least 50 percent of new residential units to be attached single family housing or multiple family housing” or prove why they shouldn’t. Armed with the same state law, regulators also set average density minimums throughout the metro area: six or more homes per buildable acre for smaller cities, 10 or more homes per acre for bigger ones.

All of this amounted to a “sweeping reform of the practice of low-density, class-based exclusionary zoning,” according to Robert Liberty, a former executive director of the anti-sprawl group 1000 Friends of Oregon who discussed the 1978-1982 upzone in a 2003 law review article that proposed further political alliances between environmentalists and housing-affordability advocates.

In Oregon, Liberty told me in an interview, “you do see more mixtures of uses, more density, more apartments in suburbs.”

Liberty’s article shared a 1982 calculation from 1000 Friends that the three-county metro area’s housing capacity had grown in those four years from 129,000 to 301,000 homes, a 112 percent increase after accounting for newly urbanized land.

Oregon’s statewide upzone came at a time when cities elsewhere like (for example) Los Angeles were aggressively downzoning.

In retrospect, Oregon’s forced upzone was timed perfectly. When it happened, the state’s economy was cratering amid rapid decline in the wood industry; most Oregonians probably feared long-term disinvestment more than overinvestment. But that upzone laid the groundwork for the moment when, a few years later, Oregon would resume its long economic boom—and unlike metros that hadn’t significantly upzoned recently (like, for example, San Francisco or Boston), Portland and its existing suburbs would prove able to build homes for people to fill the hundreds of thousands of new jobs that began to accumulate there.

It’s impossible to know if this upzoning would have happened without state action, of course. Both Seattle and its economy have grown even faster than Portland’s, despite no such state mandate.

But it does seem certain that when this upzone was happening, Oregonians generally liked their land-use mandates. Ballot measures to repeal Senate Bill 100 failed by 10-to-20-point margins in 1976, 1978 and 1982.

Cascadia’s best path to more homes: Evolution or revolution?

Today, Portland, like the rest of booming Cascadia in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, suffers from a long-term housing shortage.

It’s the defining issue of the region. It roils every political campaign. It motivates ordinary people to unprecedented feats of public-meeting attendance.

A relatively modest bill, legalizing ADUs statewide, passed Oregon’s legislature last year. (Trying to avoid the pitfall of Washington’s earlier ADU legalization, Senate Bill 1051 allowed cities to subject ADUs only to “reasonable” regulations—another case of Oregon legislators leaving the details to courts and regulators.) As in Washington, Oregon faces renewed talk about new state-level upzoning bills.

But does Oregon even need more state-level legislation, when it already has the region’s strongest upzoning laws in place?

In theory, Senate Bill 100 could be the basis to require a new round of upzoning: for transit-oriented towers like British Columbia’s, for low-rise apartment buildings in well-off suburbs, or the sort of simple corner fourplexes that Portland allowed for decades but has since banned. Enforcement could come from state regulators, from the Metro regional government or from court orders after lawsuits from housing advocates.

“There’s statutory and rule authority and goal authority to do all this stuff,” Ed Sullivan, a veteran Oregon land-use attorney who founded the nonprofit Housing Land Advocates, told me. “Metro has the ability to do it too, but they like to talk more about furry animals.”

Sullivan said Oregon law should require wealthy cities like Lake Oswego to be “increasing density, looking at integrating neighborhoods—God forbid!—looking at class at least, if not race. … And become less white.”

“I think everybody’s just afraid of blowback,” he said.

Sullivan said Oregon’s housing advocates are caught in a balancing act similar to school desegregation advocates in the decades after the U.S. Supreme Court ordered racial integration “with all deliberate speed.”

Move too fast, trigger backlash and upset Oregon’s general consensus that state and regional land-use policy is good. Move too slow and lose the sense of momentum and inevitability that makes consensus matter in the first place.

Sullivan believes progress could come from various directions: from the state legislature, with new legislation; from federal law, thanks to the “affirmatively furthering fair housing” rule made possible by a 2015 Supreme Court ruling; or from existing state law, triggered by advocates who set a precedent by winning a ruling against some particularly exclusionary city.

In the meantime, Oregon is caught in a limbo much like Washington’s, waiting for its 1993 ADU legalization to blossom into actual ADU construction, or British Columbia’s, constantly balancing regionalism against the risk of local rebellions.

Not currently on the table in Oregon or Washington: any attempt to mimic British Columbia’s approach of tweaking incentives to make cities want more housing to be legal, either because of threats to their funding streams or growth for their tax base.

Not currently on the table in British Columbia: any attempt to mimic Oregon or Washington’s approach of simply requiring cities to allow more housing.

Across the Pacific Northwest, laws about housing continue to shape public opinions about housing, and vice versa. At the state and provincial level, everyone is watching everyone else, waiting for sudden movements. And in a thousand city hall hearings, a thousand hand-to-hand battles are raging on.

Comments are closed.