After months of deliberation, Portland’s planning commission gave other cities of the Northwest and beyond a peek at what can happen when housing advocates outnumber housing opponents: It recommended more housing.

The most provocative housing policy event of this week in the Pacific Northwest started happening four months ago.

That’s because, in May, Portlanders did something almost unheard of in the world of housing policy. They showed up to say that in order to better-integrate neighborhoods and prevent future housing shortages, the city should allow more housing.

The place: Two public hearings of the Portland Planning and Sustainability Commission to discuss the residential infill project, a proposal to re-legalize duplexes and triplexes in much of Oregon’s largest city, reversing a 1959 ban.

The hearings were packed with people on both sides of the issue. But in the end (and here’s what was truly unusual) the people calling for the city to re-legalize more homes in more varieties slightly outnumbered the ones who showed up to defend the status quo—55 percent to 45 percent.

And last week, after months of deliberation, Portland’s planning commission gave other cities of the Northwest and beyond a peek at what can happen when housing advocates outnumber housing opponents: It recommended more housing.

This debate is the same one happening right now in small areas of Seattle and citywide in Vancouver, B.C. And in Portland, Team Housing just notched a clear win—cuing up the concept for a possible victory at the city council in the spring.

In that sense, the Portlanders who showed up for housing in May are part of something much bigger than an advisory vote in their city about re-legalizing triplexes. They’re part of a movement, led in large part by Cascadia, to revive a more traditional pattern of housing than the one cities began experimenting with after World War II.

The vision is simple: gradually creating neighborhoods where more expensive detached homes and more affordable small plexes are all mixed together.

Planning commission says: Cap building sizes, but let them get slightly bigger for each additional home they create

In a series of straw votes Tuesday, the commission endorsed a set of policy changes designed to stop the gradual mansionization of Portland by capping the size of new homes, re-legalizing structures that include more than one home inside and—crucially—allowing buildings to get slightly bigger (about 500 square feet on most lots) for:

- each additional home;

- creating homes affordable to lower-income households; or

- saving and lightly modifying an older structure as part of internally dividing it into multiple homes.

This crucial final part of the proposal, intended to give owners a reason (other than the goodness of their hearts) to create more and cheaper homes when they redevelop their property, had been recommended in May by numerous housing advocates.

“We have a chance to make our neighborhoods truly more diverse, both economically and culturally,” said Diane Linn, executive director of Proud Ground, a community land trust that partners with Habitat for Humanity to lower barriers to homeownership, in her May testimony supporting the size incentives. “If we don’t, shame on us.”

Also part of Tuesday’s recommendation: Increasing the maximum number of homes on a lot to three or, depending on the outcome of one last planning commission vote this fall, four.

The basic idea, though, is the same as it’s been since Portland’s council approved the general concept in 2016. The goal is to reduce demolitions of one small house for one big house, and incentivize things the public has an interest in having more of: homes, especially less expensive homes, especially ones that rehab old structures instead of demolishing them.

For example, a new home on a 5,000 square-foot lot in Portland’s most common residential zone could have up to 2,500 square feet above ground. Each home inside a new duplex could average up to 1,500 square feet; inside a triplex, 1,167.

If at least one new home on the site were made affordable to a family earning at most 80 percent of Portland’s median income (up to $58,640 for a family of three, for example), then duplex homes could average up to 1,750 square feet; triplex homes, 1,333.

The commission didn’t propose letting fourplexes be any larger than a triplex, so if it decides to recommend up to four homes, homes in market-rate fourplexes would be effectively capped at an average 875 square feet.

‘The biggest carbon impact of new construction is how big it is’

To prevent “looming” buildings, heights would be capped at 30 feet above the lowest point on a property, down from the highest point on the property under today’s rules.

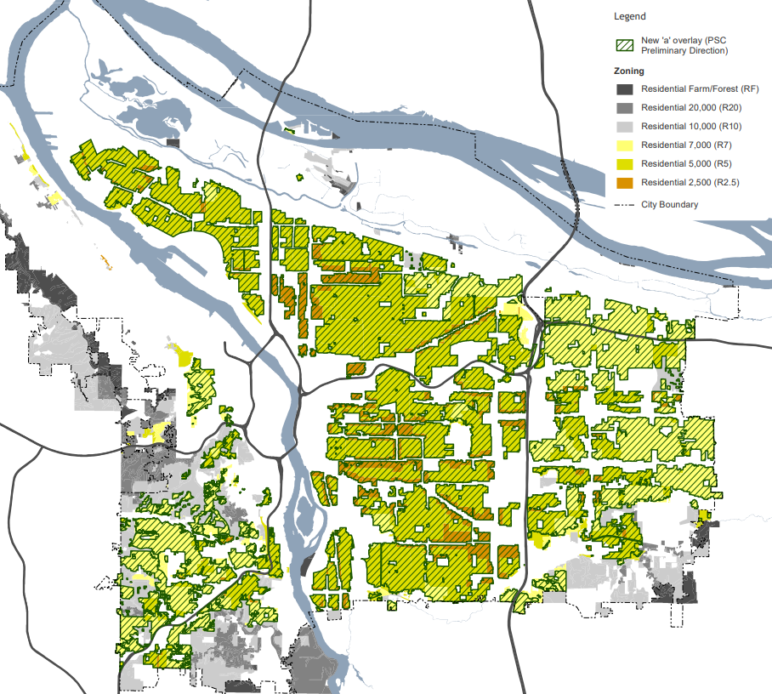

As housing advocates (including the city’s own housing bureau) suggested, the planning commission also said duplexes and triplexes should be legal (and subject to the new size caps) almost anywhere in the city.

“Density is an important goal, and I think that’s a direction the city needs to move in,” Andrés Oswill, the planning commission’s youngest member, said Tuesday. “I’m proud of the work we’ve done.”

Oswill said his decision to support the cap on building size had been informed, in part, by his own home search over the last few months.

“I really struggled and tried to understand 2,500 square feet … being too small,” he said. “It wasn’t something I was able to come to terms with.”

Eli Spevak, another commissioner, agreed.

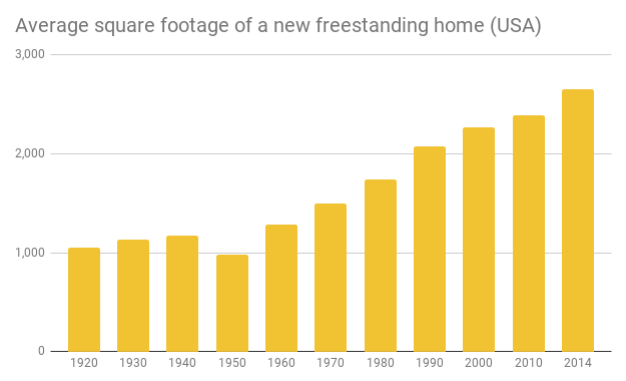

“For all the talk about We can’t fit into this 2,500 square foot house, I kind of think, well, we did for most of human history, in houses half that size,” Spevak said. “I also think about the carbon issues. Oregon has studied this more than any state. The biggest carbon impact of new construction, over the lifespan of a house, is how big it is. Seventy, 80 percent of the carbon impact of a house is heating and cooling the space. … Attached housing is great for that also, and this code supports both those things: attached housing and small homes.”

Spevak is right: North American home sizes have risen sharply since the 1950s.

In fact, that’s almost economically inevitable. As long as the only profitable way to redevelop a one-home property is to replace it with another detached home, then each successive home on a lot will be bigger than the last.

Unresolved issues: Fourplexes and displacement-risk areas

The planning commission’s straw vote Tuesday follows three years of formal debate so far over the proposed zoning reform and precedes a formal (but nonbinding) recommendation to Portland’s city council. The city council’s binding vote is scheduled for the spring.

Some issues still need resolution. The planning commissioners who were present Tuesday split evenly over the question of whether to allow up to four homes on a lot.

“As we’re asking the single-family neighborhoods to transition, it’s a big change,” said one commissioner, Michelle Rudd.

Another, Chris Smith, disagreed.

“What do the neighbors have to be afraid of?” he said. “It’s buildings, people or cars. … If it’s buildings, we’ve done a lot to limit the size of buildings. … We did not allow any FAR bonus for the fourth unit. so if a building becomes a fourplex, it will not be much larger than a threeplex. … If it’s about cars, I will point out that we’ve done very little in this package to limit parking. In general, we’re still allowing people to build parking.”

So any concern about fourplexes must actually be about the number or type of people living in currently exclusive areas, Smith concluded. And “I’m for letting as many people live in these neighborhoods as we can,” he said.

Another area of debate: what effect the size or unit-count incentive might have on the rate of redeveloping lots that are currently home to low-income people, and if so how to mitigate that. Oswill said he regretted the “missed opportunity of having funding streams be created out of this that could lead to equitable units or programming.”

The city’s initial plan had proposed extending the duplex-triplex ban in areas with the highest risk of displacement. But affordable-housing advocates unanimously told the planning commission that they disagreed with that approach, because it would fail to create new housing while leaving those areas just as vulnerable to one-for-one redevelopment.

“The anti-displacement folks told us the right way to limit displacement is not to limit development opportunity but to deliver anti-displacement programs where they’re needed,” Smith said. “The question I still worry about is, well, what happens if council doesn’t fund any of those programmatic solutions?”

Madeline Kovacs, coodinator of the pro-housing Portland for Everyone coalition, said Thursday that she had the same concern, but that extending the duplex-triplex ban would only lead to more one-for-one displacement while the city waits for political consensus around more funding.

“We know what’s happening in Portland’s neighborhoods right now,” Kovacs said. “Even if this were just a little bit better than the status quo, that wouldn’t mean that we should wait more years rather than make these changes now and then continue to improve upon them.”

In the end, that’s the only way any major rethink of Cascadian housing policy will happen: bit by bit. But if anything is going to change at all, it’s going to depend on people choosing to show up and tell one another what they want—one public meeting at a time.

Comments are closed.