Southern Oregon regulators, Native American tribes, and local communities are worried that a proposed fossil fuel facility will, among other chaos, pollute water resources and irreversibly damage wildlife populations.

If approved, the Jordan Cove Energy Project would put a behemoth liquefied natural gas (LNG) export facility in Coos Bay. The plan was believed to be dead in 2016 after federal regulators denied key permits, but the latest incarnation enjoys the backing of President Donald Trump’s administration. Before construction can begin, the US Army Corps of Engineers and the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality must sign off on water quality permits.

The stakes are high as the proposal’s two core elements would both impair water quality. The first, a supply pipeline to carry natural gas from Malin, Oregon, to Coos Bay; The second, a liquefaction facility to convert the gas into a liquid suitable to export on oceangoing ships. Oregon’s Department of Environmental Quality and the US Army Corps of Engineers are accepting public comment by mail, fax, or email until Aug. 20, 2018.

Here’s a closer look at the many risks this project presents:

Pacific Connector Gas Pipeline

The 229-mile Pacific Connector Gas Pipeline (PCGP) would stretch across remote and rugged forestland in southern Oregon. All told, the pipeline would cross 485 wetlands and waterways. That includes big rivers like the Rogue and the Klamath, as well as smaller ones like the South Umpqua, and the north and east forks of the Coquille. All of these are federally recognized for their pristine habitat or cultural value and seventy-four are home to fish.

The map below, created by Klamath Riverkeepers, shows a rough path for the pipeline.

To get the pipe across larger rivers, construction crews bore a hole under the stream and lay the pipe through the hole. The technique is known as horizontal directional drilling. While the method is intended to minimize disruption, it comes with some nasty risks. Among many hazards, pressure from the drill can cause surrounding surfaces to fracture, allowing drilling lubricants to leak into the bedrock, permeable soils, or up into the rivers. Since horizontal directional drilling is generally used in sensitive areas, these “frac-outs” can introduce sediment or salt to the wrong areas and become quite harmful to already-fragile environments.

Downplaying alarm over that possibility doesn’t hold water, either—Coos County has already seen frac-out damage from other projects. In 2009, a judge ordered builders of a Roseburg-Coos Bay pipeline to pay $1.5 million in penalties for violating the Clean Water Act after a lawsuit filed by environmental groups revealed sediment and frac-out contamination in streams. It’s unclear how—or if—the Pacific Connector project could promise to avoid the same pitfalls, especially because the project backers lack key information about the geological and hydrological characteristics of the drilling locations. Horizontal directional drilling would be used to cross the Rouge, Coos and Klamath rivers, as well as Coos Bay, where a frac-out could harm shellfish cultivation.

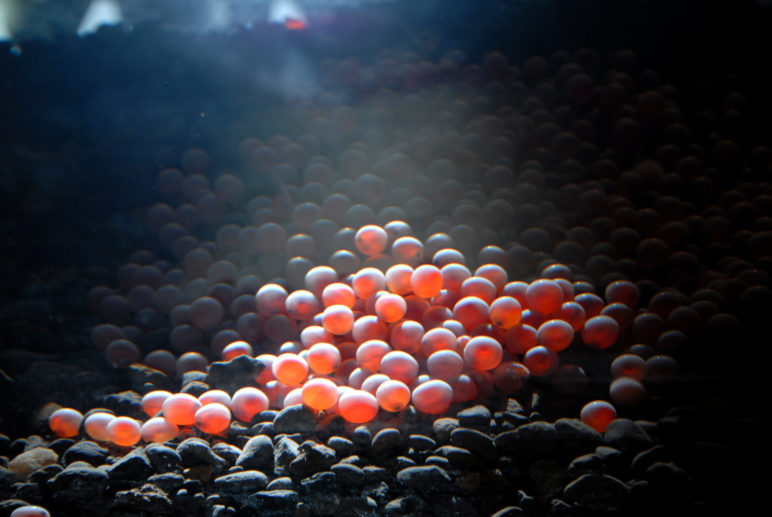

For the other streams, construction crews would use a more disruptive, cheaper drilling method called dry open-cut crossings. Methods differ but in general it means water is diverted away from a construction area while workers complete pipe-laying. In larger rivers like the South Umpqua, the natural flow of water would be disrupted for weeks. Open cuts can increase “turbidity” and suspended sediment, which can clog gills, increase stress, and suppress immune systems in fish. When the sediments settle, they cover the gravelly river bottoms—key spawning habitat for salmon. Along the banks, workers are likely to clear trees and other vegetation. In addition to causing erosion into the rivers, removing shade allows the water’s temperature to rise.

Combined, these effects would further diminish rivers already struggling to support salmon populations. In 2016, the Klamath River saw the lowest return of salmon ever recorded, a result of too-warm water. Healthy salmon runs are vital to local tribes and many of them were federally guaranteed treaty rights to fish in their ancestral waters.

The project could also put to waste tens of millions of Oregon taxpayer dollars, invested with the aim of improving salmon runs. The Oregon Watershed Enhancement Board spent $16.8 million to restore the Coos subbasin, $18.2 million on the Coquille subbasin, and $11.2 million on the Upper Rogue subbasin. The pipeline would also work against a plan to remove four Klamath River dams that today cut off salmon and steelhead from accessing more than 300 miles of habitat.

The pipeline wouldn’t just affect fish. It could also compromise freshwater used by the region’s residents. The pipeline would cross twelve drinking water source areas relied on by cities, school districts, and businesses. It would also cross upstream of four public drinking water intakes and 812 private intakes. Spills or leaks in any of these areas could introduce contaminants to the drinking water.

Even if there’s never a spill, the increase in sedimentation from construction and erosion can complicate effective water treatment. These sediments may also carry contamination from agricultural fertilizers and pesticides, stormwater runoff, or industrial pollutants. In the Umpqua National Forest, for example, there is potential for the sediment to be contaminated by mercury deposits.

Once the pipeline is laid, a leak-check called hydrostatic testing would be done. The test pushes huge amounts of water through the pipes and the area is then inspected for spraying or puddling water. The Pacific Connector project could use 15-million to 60-million gallons of water, pulling from nearby rivers, lakes, and aqueducts. Despite a slew of questions by the US Forest Service, there’s still scant detail on water usage for the project. Experts worry that the water transport will introduce invasive species.

The pipeline would also leave permanent scars on the landscape. A thirty-foot-wide swath of right-of-way would be kept, where no trees would be permitted to grow. Erosion-prone roads decommissioned by the Forest Service would be rebuilt to provide access to the pipeline, and fifteen miles of new, permanent access roads would remain after construction is completed. Even gravel roads can desecrate an ecosystem by fragmenting wildlife habitat, introducing invasive plants, and increasing sedimentation and vehicle-pollution runoff.

Jordan Cove LNG Terminal

The terminal itself is designed to export a whopping 7.8 million metric tons of liquefied natural gas each year. It would dominate 538 acres of land on the northern banks of Coos Bay with a liquefaction facility, storage tanks, and marine export facilities.

About 6.4 million cubic yards of silty ocean floor would have to be removed at first, plus an estimated 34,600 cubic yards annually for maintenance.

Building and operations would impact the bay in myriad ways. A massive berth and deeper, longer channel would need to be installed to accommodate ships capable of transporting as much as 217,000 cubic meters (about 650 Olympic-sized swimming pools) of LNG to customers in Asia. That project would affect another 95 acres of Coos Bay. It goes without saying that’s a lot of dredging: about 6.4 million cubic yards of silty ocean floor would have to be removed at first, plus an estimated 34,600 cubic yards annually for maintenance.

The shallow subtidal habitat in Coos Bay is a critical home for crabs, shrimp, clams, and gray whales. Dredging would remove and impair much of this coastal habitat. Not to mention, the previous dredging in Coos Bay unearthed soils contaminated with metals, hydrocarbons, and PCBs. That soil was then deposited on the site where the LNG terminal would be built.

Many worry that a new round of dredging will turn up more of the same pollutants from Coos Bay’s history of heavy industrial use. Dredging can also kick up sediment and increase turbidity, which, just as it is in streams, is detrimental for marine wildlife. When the sediments are contaminated, the pollution can work its way into the shellfish that are farmed along the bottom of Coos Bay.

Local opponents of the project also raise a host of additional concerns. They argue that the channel dredging and pipeline construction may cut through historical tribal villages located on the shifting, estuarine lands of Coos Bay—it’s happened before. The LNG plant would also need water from the bay, and a lot of it, to cool the equipment. Those withdrawals might harm the habitat for threatened coho salmon. Then when the water is discharged from the facility’s cooling system, it could be warm enough to raise temperatures in part of the bay, thereby degrading its suitability for fish and other wildlife. Plus, the increased vessel traffic to and from the export terminal would interfere with commercial fishing and recreation in the area.

What’s next?

The public can comment on two key permits now under review by the state and federal agencies responsible for reviewing the project’s compliance with the US Clean Water Act. You can submit comments to Oregon’s Department of Environmental Quality and the US Army Corps of Engineers by mail, fax, or email until Aug. 20, 2018.

Thanks to Rogue Climate, Columbia Riverkeeper, and Rogue Riverkeeper who provided research and other supporting material to make this article possible.

Notes and methods: The US Forest Service comments can be found at the FERC eLibrary by searching for docket numbers CP17-494* and CP17-495*. (The FERC system does not allow viewing most files without downloading them automatically, so we do not link to specific documents here.)

Comments are closed.