[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]As summer temperatures rise and wildfire season intensifies, Northwest residents may be reminded that climate change is gradually making itself felt in Cascadia. It’s timely, therefore, to recall that climate progress is possible, both internationally and regionally, even when the current US Presidential Administration is not helpful.

Perhaps the best example of effective and coordinated climate action is particularly apt for the season: the Montreal Protocol, which reduced the use of ozone-destroying chemicals found in air conditioners and other equipment.

Put into force in more than thirty years ago with amendments added since, the Protocol also targets related, extremely potent greenhouse gases and, as a result, ushered in an outsize benefit to climate progress. The Trump Administration publicly supported the expansion—at least at first. But backing was short-lived before Trump appointee Scott Pruitt took advantage of a decision written by Judge Brett Kavanaugh (yes, that Kavanaugh: Trump’s nominee for US Supreme Court). Yet there are signs that leadership from the Northwest and California may carry the day, keeping American progress in stride with the global consensus on at least one element of climate policy.

In the absence of international agreements to protect it, two-thirds of the global ozone layer might have been gone by 2065.

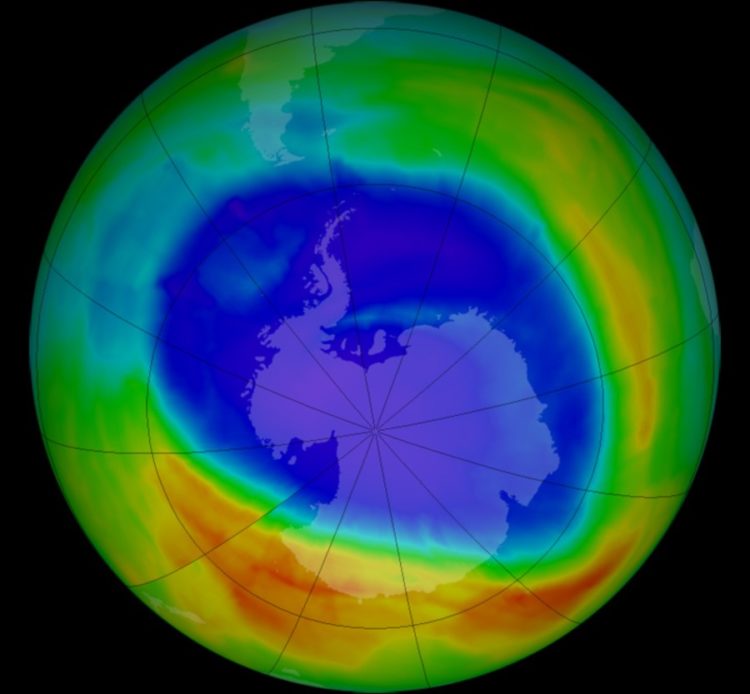

To understand why this matters, it’s useful to review some history. Scientific data in 1985 showed that chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs)—chemicals used for refrigerants, in air conditioners, and other applications—created an ozone hole over Antarctica. The US under then-President Ronald Reagan accelerated negotiations on international talks to protect the ozone layer. Thirty-one nations signed the resulting measure, dubbed the Montreal Protocol, in 1987. Reagan submitted the Protocol to the Senate, which ratified it by a vote of 83-0, making the US the first major producer and consumer of CFCs to ratify the agreement.

The Protocol included a schedule to phase out CFCs and other ozone-destroyers; it set faster cancellation schedules for developed nations and created a Multilateral Fund, financed by industrial nations, to help developing countries implement technologies to comply with the Protocol. The ozone treaty was ultimately ratified by 196 countries and the European Union, making it the first universal agreement in UN history. The Protocol, along with its subsequent amendments, represents a prime example of international cooperation to address a global chemical threat.

In 2003, former Secretary General to the United Nations Kofi Annan called the Protocol, “Perhaps the single most successful international agreement to date.”

Protecting the ozone layer is important because it reduces ultraviolet radiation—linked to eye damage and skin cancers—from reaching the Earth’s surface. Stratospheric ozone levels over Seattle, for example, declined by 8 percent between 1979 and 1994.

In the absence of international agreements to protect it, two-thirds of the global ozone layer might have been gone by 2065. Instead, the ozone hole detected over Antarctica reached its peak size in the mid-1990s and may return to pre-1980 levels by 2075. (Scientists also detected a smaller ozone hole over the Arctic.) A 2015 scientific analysis based at the University of Leeds concluded that without the Protocol, the Arctic ozone hole could have expanded in area by 40 percent, along with ozone depletion up to 15 percent at mid-northern latitudes, including Europe and the US Pacific Northwest.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Eight amendments later, the Protocol’s participating nations agreed to speed up the phase-out schedules and restrict additional ozone-eating chemicals. The most recent modification—the 2016 Kigali Amendment—was added to the Protocol to focus on hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs). Phasing out CFCs gave way to use of HCFCs; phasing HCFCs gave way to use of HFCs. The latter are greenhouse gases that don’t attack ozone but, molecule to molecule, are about twelve-thousand times more damaging than carbon dioxide. Recognizing this damaging impact on the global climate, nearly 200 countries agreed to phase out HFCs.

Phasing them will avoid the equivalent of 1.2 billion tons of carbon dioxide emissions, equal to nearly one-fifth of US greenhouse gas emissions during 2015.

Gina McCarthy, the chief administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency under President Barack Obama, reported in October 2016 the HFC phase-out alone could avoid up to one-half degree centigrade of global warming by this century’s end. President Obama’s EPA also issued regulations in 2015 that would phase out HFCs in the US, but two foreign companies sued and put action on hold.

The NASA animation below shows what the ozone layer might have looked like 1974-2060 if there was never a CFC ban. Warm colors indicate more ozone.

By NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center Scientific Visualization Studio – NASA, Public Domain, Link

About a year later, at a celebration of the 30th anniversary of the Montreal Protocol, a longtime US State Department official spoke on behalf of the Trump administration and gave support for the Protocol and the Kigali Amendment.

For its part, the air-conditioning industry endorsed the Kigali Amendment, too, and manufacturers planned to sell cooling units with chemical alternatives to HFCs to millions in India, Pakistan, and other hot climates.

In the meantime, twenty countries have ratified the amendment, meaning that it goes into force in January 2019.

Then the Trump administration began changing its tune.

Trump’s proposed 2018 budget zeroed out US contributions to the Protocol’s multilateral fund. Congress, fortunately, restored $31 million to the Fund, thus facilitating the ability for developing nations to purchase “greener” US air conditioners.

Meanwhile, the US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit handed a blow to Obama’s HFC ban. In a 2-1 decision authored by Kavanaugh, the EPA was wrong to use a section of the Clean Air Act to justify the HFC phase-out. That particular section required manufacturers to find safe alternatives to ozone-depleting substances.

“The fundamental problem for EPA is that HFCs are not ozone-depleting substances,” Kavanaugh wrote, adding that the section “does not require (or give EPA authority to require) manufacturers to replace non-ozone depleting substances such as HFCs.” The decision made it clear the EPA can’t force a company already using HFCs to switch, but it can still add HFCs and other greenhouse gases to a list of banned alternatives to HCFCs and CFCs.

The court also vacated part of the rule, returning it to EPA for further consideration—leaving it up to Trump’s EPA to decide the next move.

Scott Pruitt, then head of EPA, responded in April 2018 with a “guidance document,” announcing that EPA would not enforce any part of the Obama-era initiative related to HFCs, pending further rulemaking proceedings. Eleven states, including California, Oregon, and Washington, sued the EPA in June 2018. The states argued that the guidance document essentially removed all provisions related to HFCs and demands the federal agency to at least enforce the parts of the rule unchallenged by the Court.

California is blazing its own trail toward removing HFCs. A 2016 state law required reductions in HFCs, and in March 2018, the California Air Resources Board (CARB) adopted regulations to prohibit the use of HFCs. Michael Gerrard, the director of the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia University, remarked that “California’s adoption of its own HFCs standards may well inspire other states to do the same, especially since there are readily available substitutes.”

Also in 2016, California joined with Oregon, and Washington, and British Columbia to develop the Pacific Coast Climate Leadership Action Plan. Among many other provisions, these jurisdictions promised to include HFCS and other “powerful climate-forcing pollutants” in annual reporting of greenhouse gas emissions, with a goal of considering “reduction targets for these gases by 2020.”

The Plan is a promise, in a way, that cooler heads in leadership from the Northwest and California may yet prevail over the hot air from those who deny the reality of a warming climate.

John Abbotts is a former Sightline research consultant who occasionally submits material and research.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Comments are closed.