The Northwest is poised between promise and peril. The coming years could usher in a golden era of low-cost and low-carbon transportation centered on electric vehicles and new technology. Or the region could sink deeper into the mire of an ever-expanding oil industry.

Either future is possible. But in recent months, the oil industry has seemed ascendant.

Over vehement objections from indigenous communities, and in spite of the risk of oil spills and global climate change, the government of Canada is forging ahead with plans to build a huge new pipeline from Alberta’s tar sands to the Salish Sea. Yet the Trudeau Administration’s pipeline expansion is just the latest in a long series of moves by the oil industry to broaden its reach in Cascadia—and Washington’s coastline is a prime target. Home to refineries, shipping terminals, pipelines, and oil train depots, the shores of Puget Sound have seen decades of relentless infrastructure expansions.

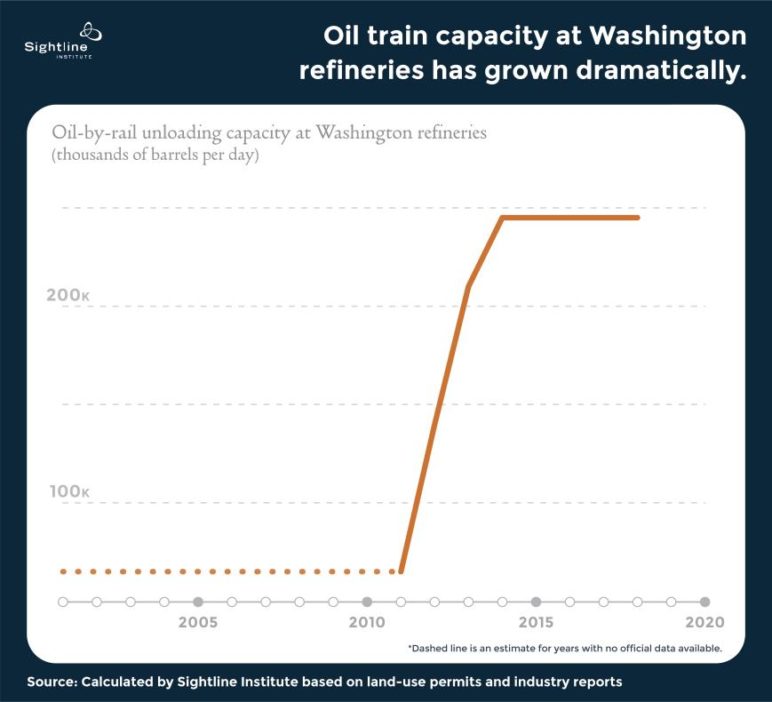

Consider crude oil-by-rail. Since 2012, four of the five Puget Sound refineries have built facilities to accommodate massive trainloads of volatile oil from North Dakota. (The fifth tried, but tribal and environmental advocates stalled the project.) Prior to those expansions, Northwest refineries could handle at most modest shipments of petroleum by rail. But the build-out of oil train unloading infrastructure allowed refineries to handle mile-long “unit trains” filled with crude oil—sharply sending up the state’s oil-by-rail capacity.

Refineries are not the only destination for oil trains on Puget Sound. In 2014, Targa Terminals in Tacoma expanded its capacity to unload rail cars. Now able to handle 36 rail cars at once, up from 24, the Targa facility can offload perhaps 40,000 barrels of crude per day delivered by train. Plus, terminals in Portland and Clatskanie, Oregon, draw even more oil trains through Cascadia, most of them traveling through Spokane and across eastern Washington.

To take advantage of the influx of light crude delivered by rail, the oil refiner Andeavor (formerly Tesoro) now aims to expand its Anacortes operations to produce xylene at its refinery. The company may soon get the permits it needs to ship tankers full of the petrochemical to feed Asia’s appetite for manufacturing plastics.

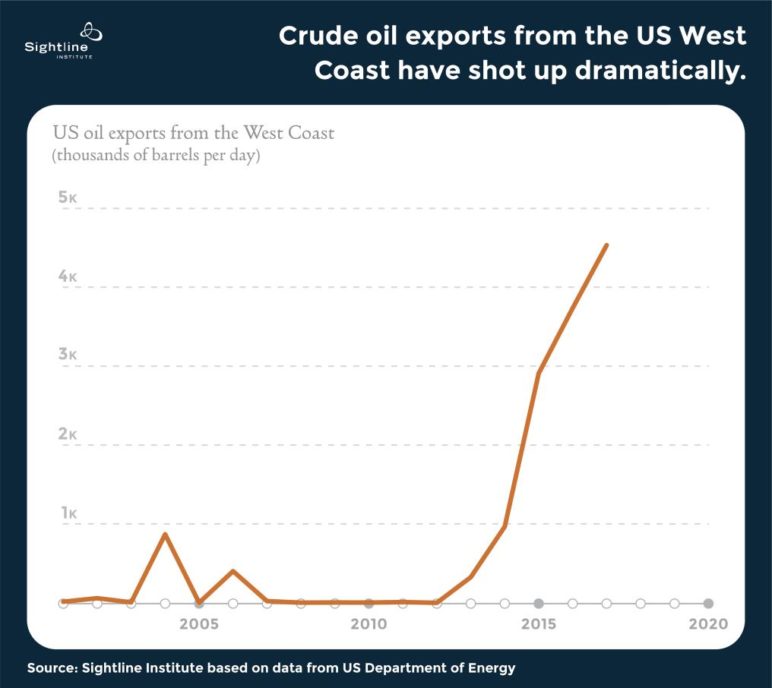

Xylene tankers are hardly the only new shipping threat to the Salish Sea. In 2015, the Obama Administration lifted a four-decade-long ban on exporting US oil, potentially freeing up much of that unprocessed fuel for foreign buyers. State-level data are not available for Washington, but the US Energy Department reports a spike in crude oil exports from the West Coast.

In the absence of the ban, it is now possible for Washington refineries to simply export crude oil from their piers without first refining it into usable consumer products. Yet because no official agency reports Puget Sound-specific data, we do not know precisely how big a role these ports play in the story of West Coast exports, though it could be playing a meaningful role.

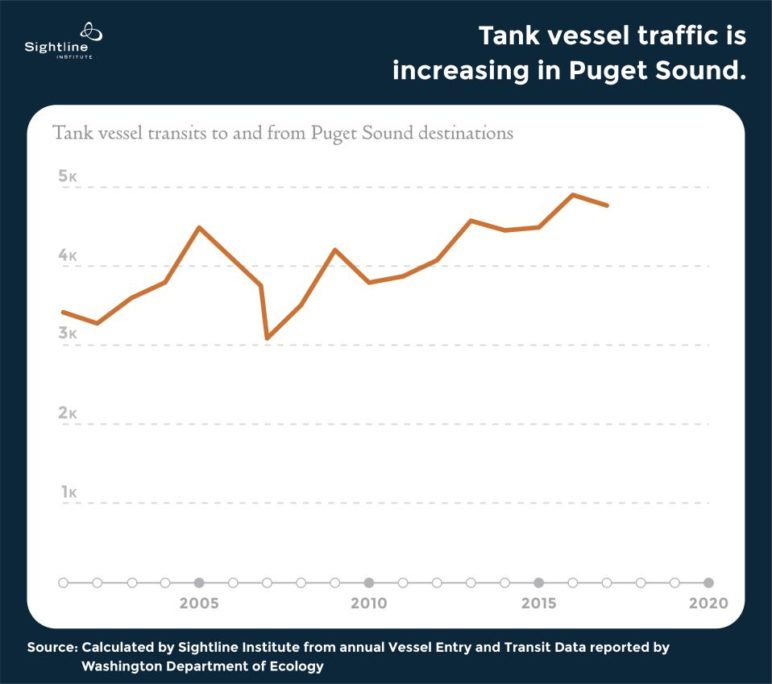

Each vessel shipment of crude oil, refined fuel, and petrochemicals contributes incrementally to the growing risk of a spill in the Salish Sea. Worrisomely, data from the past decade reveal rapid growth in oil and oil-product tankers sailing to and from Puget Sound destinations. In fact, its waters see roughly three more tank vessel transits each day than they did twenty years ago.

Much of the increase can be attributed to a shift in the type of vessels favored by terminal operators. Big tanker ships are falling out of favor, making way for a growing fleet of smaller tank barges. The number of big tankers entering Puget Sound via the Strait of Juan de Fuca peaked prior to 2010, even as the industry added hundreds of tank barge transits. Overall, the number of tank vessel trips is clearly increasing over time, each one adding to the growing risk of a spill contaminating the waters and shorelines of the Salish Sea.

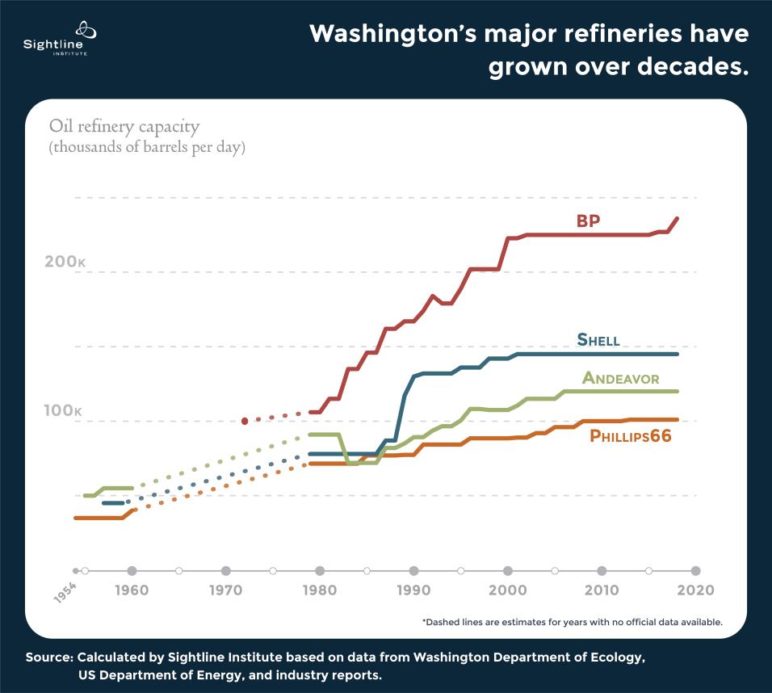

On land, a network of oil pipelines feeds into refineries and port terminals in the Northwest. These too are poised for growth. Having paid handsomely for it, Canada’s Trudeau Administration hopes to triple the capacity of the Trans Mountain oil pipeline in southern British Columbia and also perhaps double the system’s extension into Washington, the Puget Sound Pipeline. Anticipating a new flood of heavy oil, BP is undertaking an expansion of its Whatcom County refinery.

BP’s move is not without precedent. Notwithstanding a recent plateau, history shows long-term growth in refining capacity at the four big north Puget Sound oil refineries.

The majority of the petroleum products consumed in Cascadia—our gasoline, diesel, jet fuel, and more—are refined at these four facilities. They drive the supply of carbon-based fuel for the Northwest’s transportation system. They are the customers for oil trains, tankers, and pipelines. They are four of the top seven “point source” carbon polluters in the state, responsible for over 26 percent of Washington state’s greenhouse gas emissions from large industrial facilities. And they form the backbone of the oil industry’s political muscle in the region.

In recent decades, Puget Sound refineries moved overwhelmingly in one direction: towards more. More refining capacity, more oil-by-rail handling, more tanker traffic, more carbon pollution, and more risk of a devastating spill. Even the vaunted “Magnuson Amendment,” a federal law designed explicitly to freeze the state’s oil industry at 1977 levels (not counting local consumption), represented little more than a speedbump in the oil industry’s road to further expansions.

What’s next for the Northwest’s oil industry? In Canada, First Nations and environmental activists are preparing for a Standing Rock-like showdown over the Trans Mountain Pipeline expansion, probably with backing from provincial and local leaders, while the federal government insists it will force through the new pipeline over any objections. Meanwhile, south of the 49th parallel, leaders in Oregon and Washington are crying foul over Trump Administration plans to allow drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, which would likely supply crude oil Puget Sound refiners, and to open up drilling off the Northwest coast.

There’s no telling whether oil companies will be able to continue their decades’ long project of growth or whether Cascadia’s opposition movement will draw a line. The Thin Green Line, the Northwest’s resistance to fossil fuel schemes, has notched big wins against the oil industry recently, but major clashes are likely in the years ahead.

Ahren Stroming is a research contributor to Sightline. He’s a former policy analyst for the City of Seattle Office of Sustainability and Environment and a current graduate student at the University of Freiburg in Germany.

Thanks to John Abbotts for supporting research and to Jim Lazar whose insights inspired this article.

Notes and methods

Our data on West Coast oil exports refers to the “PADD 5” region, which includes Alaska, Arizona, California, Hawaii, Nevada, Oregon, and Washington. While crude volumes shipped from the West Coast have grown since the Obama Administration lifted the export ban, the ban was not watertight even while it was in place. Companies could sometime obtain export licenses from the Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) and the Commerce Department, subject to a set of rules published by the Department of Energy. Exports before the ban was lifted often coincided with periods of high American crude production and low prices. For instance, almost all West Coast exports in 2015 occurred in April, one month after the price of American crude crashed.

The four north Puget Sound refineries we analyze are not the entirety of the region’s oil industry, but they comprise the bulk of it and they are fair indicators of overall trends. Like many other industrial enterprises, oil refining has been slowly consolidating over the past few decades with small refiners dropping out and big facilities getting bigger. On the West Coast, for example, there were 52 oil refineries in 1982 but just 31 today, while total refining capacity has hovered around 3 million barrels per day. In Washington, five refineries now process more than 630,000 barrels today where 35 years ago eight handled less than 400,000. A couple of small refineries in Oregon also closed up shop during that time. Official data show a puzzling temporary drop in refinery capacity at the Andeavor refinery between 1981 and 1983 (then owned and operated by Shell), likely owing to a reporting change rather than any actual change to refinery operations.

We are not aware of any official data available on oil train capacity at Washington’s refineries prior to 2011, so we assume a modest 15,000 barrels per day, which is consistent with our understanding of the industry’s development.

Comments are closed.