What better model for the Evergreen state than New Zealand, a beautiful, green country which used to use single-winner districts?

As the previous option explained, Washington’s dual legislative houses are repetitive and wasteful. Combining them into one makes a world of sense, but would require a constitutional amendment. If that were a possibility (perhaps after a citizens’ initiative converts the legislature to proportional representation under one of the options I described here and here) , Washington could simultaneously switch to a system of proportional representation like New Zealand’s.

What better model for the Evergreen state than New Zealand, a beautiful, green country which, like other former British colonies Canada and the US, used to use single-winner districts? In the 1990s, the Kiwis figured out the winner-take-all system wasn’t serving them, and they voted to switch to a new system that elects a mix of local representatives and regional representatives. Washington could do something similar, resulting in a more representatives house of representatives and more competition for the two major political parties.

Local and regional representatives

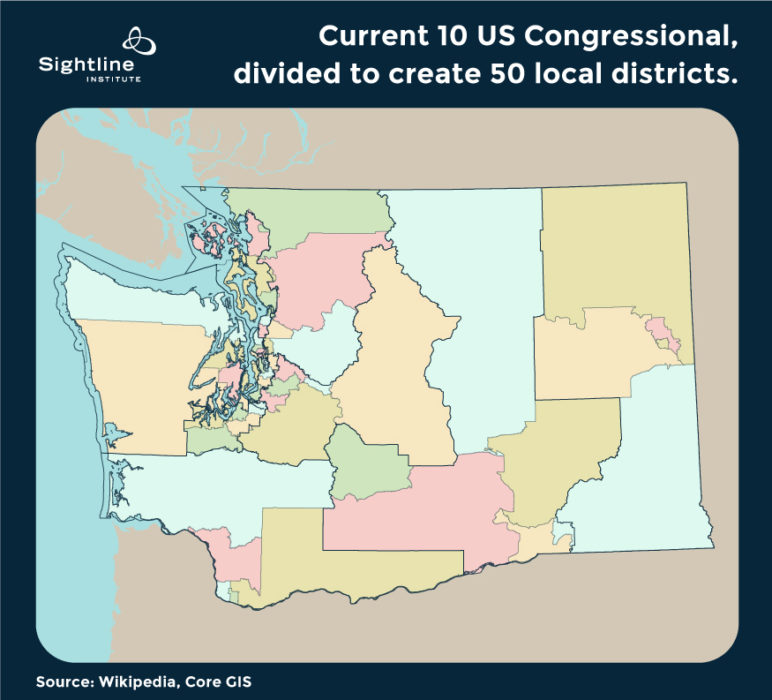

Instead of a mix of senators and representatives from the same districts but serving in different bodies, Washington could elect a mix of local and regional representatives, all serving in the same body. Washingtonians could rest assured that they could elect someone who lives in the same geographical area as them (their local representative) but also vote for or rank more than one candidate in a regional race. The Washington redistricting commission could draw 50 state legislative districts instead of 49. Drawing 50 districts could simplify the redistricting process because the commission could first draw the state’s 10 congressional districts, then divide each one into five state legislative districts for a total of 50 equal population districts.

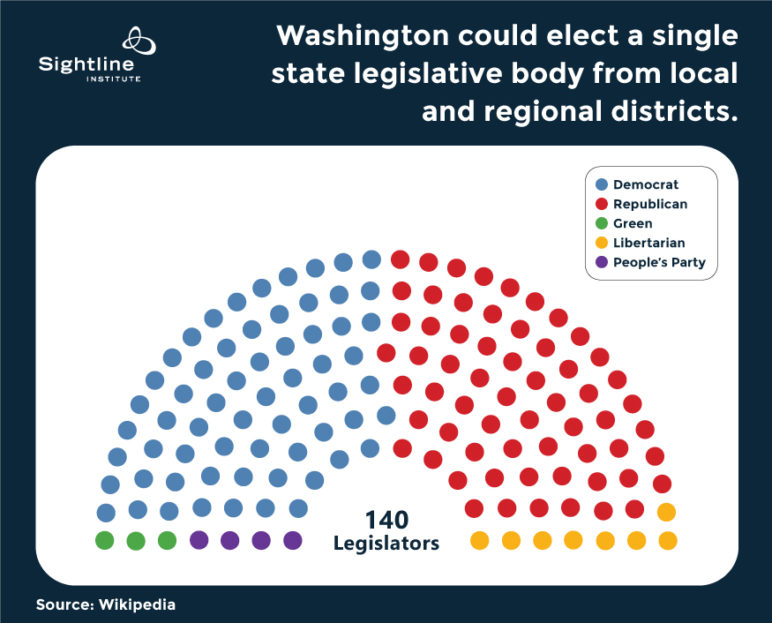

Each district would elect a local representative from a single-winner district, just like state legislative districts do now. In addition, voters would elect nine regional representatives from each congressional district to serve in the state legislature. The result would be a state legislature with 140 members (down slightly from the current 147), consisting of 50 local representatives and 90 regional representatives.

The ballot to elect nine regional representatives could be a ranked-choice ballot like in the other options.

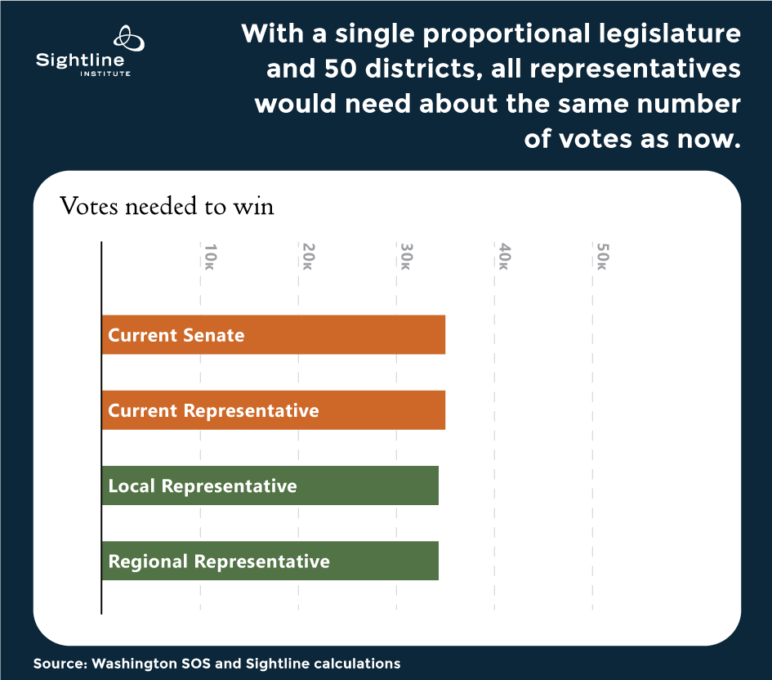

Candidates would need to win about the same number of votes as now

The threshold to win a seat in one of the 50 local districts or 10 regional districts would be almost the same as the threshold to win in one of the current 49 districts. Even though the regional district would be as big as the US congressional district, state representatives would not have to win as many votes as congressional delegates because they would be running in a pool for one of nine seats.

The legislature would be more diverse and more representative

The local representatives would look much as they do now—likely all coming from one of the two major parties. But in the regional races, voters would be allowed to vote for more than one candidate, so a greater variety of candidates could win seats. The single house overall would more fairly represent the voters in terms of their split between Democrats and Republicans, and candidates from outside the two major parties would be able to run and win. The below is just an illustration of how it might work, not a prediction of how voters and candidates would respond to a new system. But for proof that this works in the real world, see New Zealand’s legislative make-up before and after adopting this form of proportional representation.

The Kiwis did it, and Washington could too

New Zealanders wanted to move to proportional representation, but also wanted to keep the familiarity of having a local representative from a single-winner district. Making the switch but keeping two houses would create a labyrinth of state elections, with a local representative in the senate, a local representative in the house, and regional representatives in the house. Streamlining the state’s sprawling two legislative bodies into a single, more efficient, more representative body would be a big change requiring a constitutional amendment. But it could yield huge benefits: the whole legislature would function more efficiently instead of nonsensically maintaining two bodies that represent the exact same voters. Switching at the same time to mixed member proportional representation would give more voters more choice in selecting who represents them.

Comments are closed.