Amending the Washington State Constitution is notoriously difficult.

The opening article in this series laid out some of the many reasons that Washington voters might want to adopt proportional representation for the state legislature. The first path to reform is likely through a vote of the people, and luckily Washington voters could make significant improvements to state government without amending the state constitution.

Which is good because…

The legislature is unlikely to amend the constitution

Amending the Washington State Constitution is notoriously difficult. Both houses must pass an amendment by two-thirds, and then it goes to the ballot where a majority of voters must say yes. The legislature is unlikely to even consider, much less pass with two-thirds support, a reform that could threaten incumbents’ power. The current system protects incumbents from competition in elections, and they won’t want to give that up. In addition, proportional representation will challenge the two-party status quo by allowing candidates who don’t toe the party line to run, and party power brokers won’t like that either.

Any move towards proportional representation in the state legislature will come in the form of a citizen’s initiative, rather than a legislature-initiated constitutional amendment. Luckily, the state constitution leaves the door open for proportional representation. Article II of the state constitution requires:

- The house of representatives to have between 63 and 99 members, and the senate to be between one-third and one-half the size of the house, so between 21 and 49 senators (section 2).

- Representatives to serve for two years (section 5) and senators for four years, staggered every two years (section 6).

- Senate district lines to be the same as representative district lines; a senate district may not divide a representative district (section 6).

- Senators to be elected “at the same time and in the same manner as members of the house of representatives” (section 6).

What Washington has now: 147 state legislators elected from 49 districts

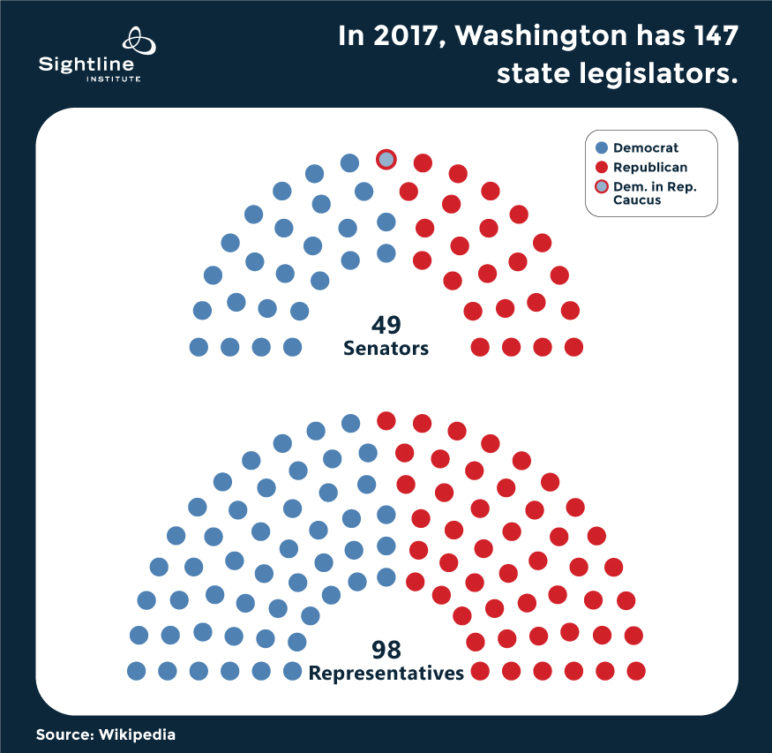

Washington currently has 147 state legislators: 49 senators and 98 representatives. One senator and two representatives are elected from each of 49 legislative districts (see RCW 44.05.090(4) and RCW 29A.24.010). (Prior to 1959, there were 42 senators and 99 representatives.)

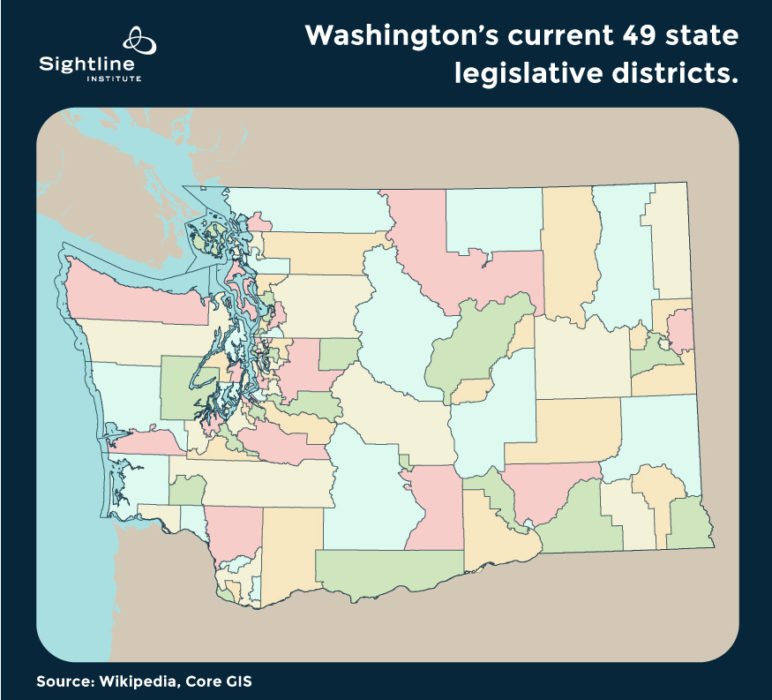

Every 10 years, the legislature appoints four commissioners to the State Redistricting Commission: the House Democrats and House Republicans each appoint one member, and the Senate Democrats and Senate Republicans each appoint one member, for a total of two Democratic appointees and two Republican appointees. The Commission draws 49 districts, and each district elects one senator and two representatives. The current map, drawn in 2011, looks like this:

After the 2011 redistricting, Republicans (plus two, and then later one, renegade Democrats) took control of the state Senate, even though Democrats have the edge among voters. This outcome was in part because the Commission, despite being bipartisan, still somewhat cracked and packed Democratic voters—packing Democratic voters into 18 districts that leaned Democratic, and cracking them across 10 districts that leaned slightly Republican. The district lines gave Republican voters more power to elect like-minded legislators than Democratic voters had power to do the same. The chart below shows the Senate prior to November 29, 2017, when Manka Dhingra, a Democrat who won a state senate seat in a special election, was sworn in, letting Democrats take control of the Senate for the first time in five years. The chart below shows the senate prior to her swearing in, when Republicans controlled the Senate because Democrat Tim Sheldon caucused with the Republicans.

What could Washingtonians do with a citizens’ initiative?

A citizen’s initiative could change the number of legislators, the number of districts, the number of senators and legislators elected from each district, and the form of the ballot, so long as it complies with the bullets above. The next two articles in this series will outline options for how Washington could switch to proportional representation without a constitutional amendment. Options 1 and 2 below.

Option #1(a) — 13 merged state districts — Keeps the same number of legislators (98 representatives and 49 senators) and the same district lines. It just merges existing districts into 13 super-districts made up of three or four current districts each. Each of the merged districts would elect either three senators and six representatives, or four senators and eight representatives. No matter what district they live in, voters would have more choices and the results would more fairly represent all voters in the district.

Option #1(b) — 14 new districts — Instructs the 2021 redistricting commission to draw 14 districts, each of which will elect three senators and seven representatives. This option elects 98 representatives (same as now) but shrinks the senate slightly to 42 members (same as before 1959). Like Option #1(a), voters would have more voice and the redistricting commission would have less power to determine election outcomes.

Option #2 — 10 US House districts — Uses Washington’s existing ten US Congressional districts and in each would elect four senators and nine representatives. Like Option #1(a), it could be implemented immediately without new redistricting and would give voters more voice. The option shrinks the legislature from 147 to 130 members—40 senators and 90 representatives.

Then, the legislature might be willing to amend the constitution

Once the legislature more fairly represents the voters, it might be more interested in implementing reforms that voters want. At that point, the legislature might be willing to contemplate the big step of combining the two legislative houses into one more efficient body. The final two articles in this series describe what could be possible if and when a streamlined legislature becomes possible.

Option #3 — merge house and senate — Describes a single Washington state legislature elected from 21 districts with seven representatives each. The legislature would have the same number of members as now—147—but they would all serve in the same house instead of doing the same things twice, as they do now. This single, larger body would have to find solutions that a majority of legislators support, but once it found such solutions it would be able to implement them without waiting for another body to go through the same process.

Option #4 — mixed member proportional — Shows how Washington could shrink the legislature slightly—to 140 members—but instead of electing them from the same districts to serve in two different houses, voters could elect local and regional representatives, all of whom would serve in one legislative body.

Conclusion

Every option in this series would give voters more choice and more voice, help break through partisan gridlock, defang the gerrymander, give voters the chance to limit special interests’ influence, and give people a chance to run for office even without the backing of one of the two major parties or big donors. More voters would be able to elect a like-minded representative, no matter what district they live in. And the two major parties would face more competition, forcing them to champion solutions that voters want.

Comments are closed.