The compact size of these unassuming homes makes them remarkably energy efficient, cutting lifetime CO2 emissions by as much as 40 percent as compared with medium sized single-family homes.

Accessory dwelling units (ADUs) are a tool in the fight against climate change. Garden suites, mother-in-law apartments, and backyard cottages—the compact size of these unassuming homes makes them remarkably energy efficient, cutting lifetime CO2 emissions by as much as 40 percent as compared with medium sized single-family homes.

Yet many of Cascadia’s cities maintain policies that pose major barriers to ADU construction, keeping this green housing option scarce. In Seattle, for example, ADUs face obstacles from height and size restrictions, parking requirements, regulations that mandate owner occupancy, among others. These barriers force climate-conscious Cascadians who may prefer a small housing choice to swell their carbon footprints in engorged homes. In Seattle at least, there may be hope on the horizon: the city council will have the opportunity to strike down some of these ADU barriers later this year, giving Seattleites more opportunities to choose green.

Small homes are greener

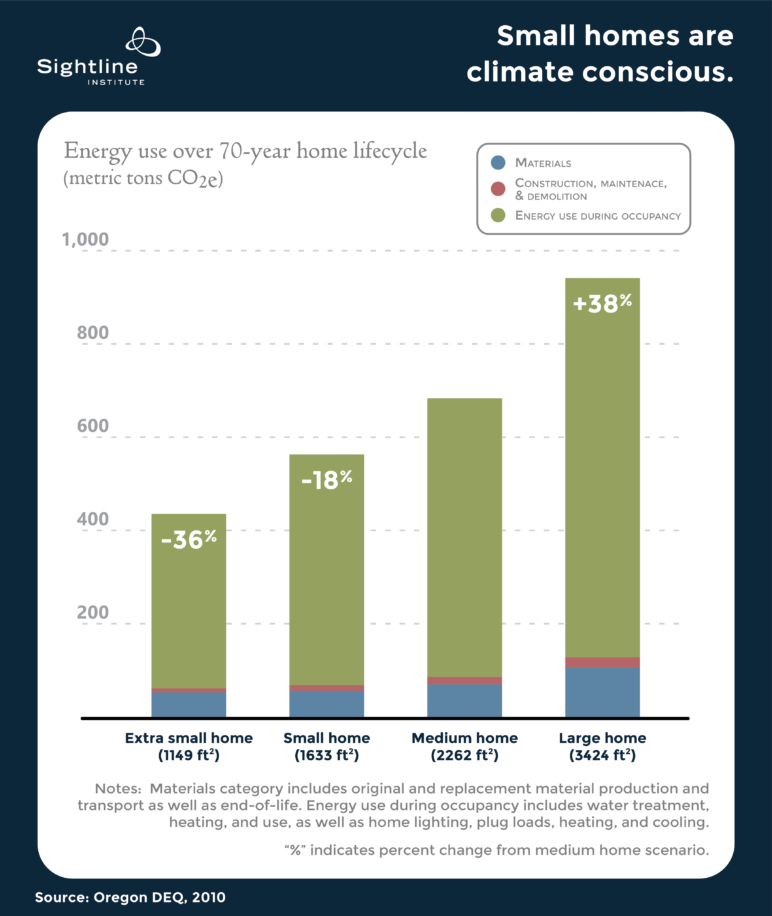

A 2010 Oregon Department of Environmental Quality report found that a typically sized new single-family home (defined as about 2,300 square feet) built to industry standards is responsible for nearly 60 percent more emissions than a home approximately half its size over the course of an average 70-year home lifespan, from construction to demolition.

As the figure below shows, the difference in climate impact is almost entirely from reduced energy needs during occupancy, for things like temperature control and lighting. A small portion of the energy savings for the small home also accrue from reduced material fabrication and transport, as compared with those of more average-sized homes. (This chart and the next measure climate impact in metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent emissions. This is a common unit of measurement in studies of emissions, which combines total effect of emissions from all greenhouse gases.)

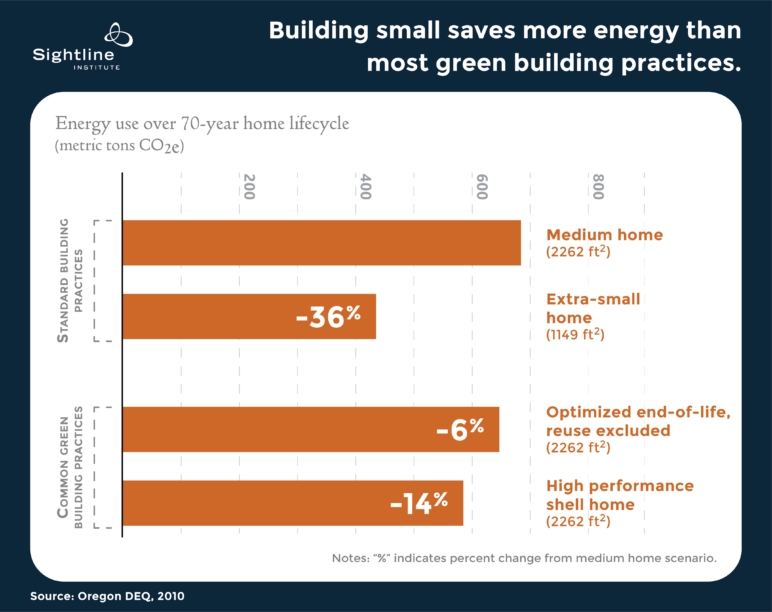

In fact, going small can have even better climate benefits than many green building practices. The same Oregon DEQ report compared energy consumption of an extra-small home (1,149 square feet) constructed according to standard building practices with that of average size homes constructed according to two popular green building philosophies: high insulation and optimized building material disposal. Green building practices and standards have come a long way since 2010, but at the time the extra-small home saved significantly more energy than the green homes. As the chart below shows, over a typical 70-year home lifespan, an extra-small home is responsible for 150 metric tons fewer CO2 emissions than a medium size high insulation home. That’s approximately the emissions from 36 average passenger vehicles over a full year of driving. The small home outperformed the optimized material end-of-life home by even more, emitting a full 212 fewer metric tons CO2 over the 70-year home lifecycle.

(The high insulation home, termed the high performance shell home in the DEQ report, was modeled after the Oregon High Performance Home (HPH) standard at the time and focused on improved ceiling, wall, and floor insulation, as well as reduced heat loss through windows. The optimized end-of-life home scenario focused on best recycling practices for all non-wood building materials and energy recovery from all wooden building materials. More detailed construction specifications of both green building practices begin on page 12 of the report.)

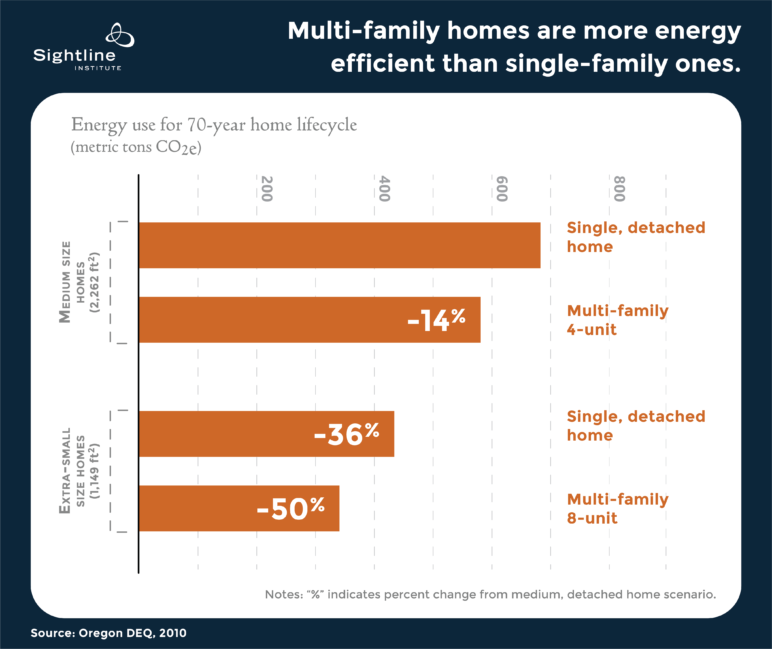

The energy savings from small homes in multi-family buildings—such as apartments, stacked flats, rowhouses, and townhomes—are even higher. That’s because the shared walls cut down not only on building materials, but also energy use during occupancy.

But a small home is hard to find

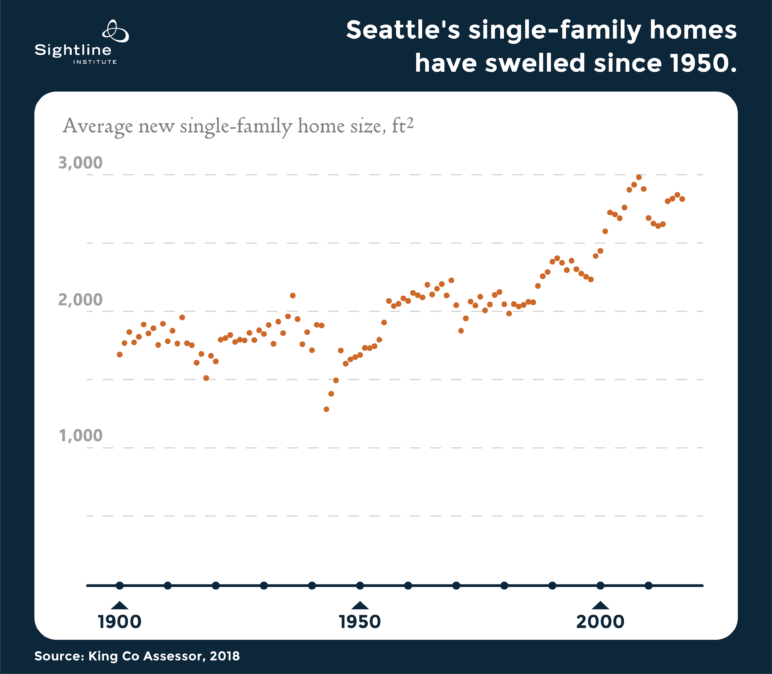

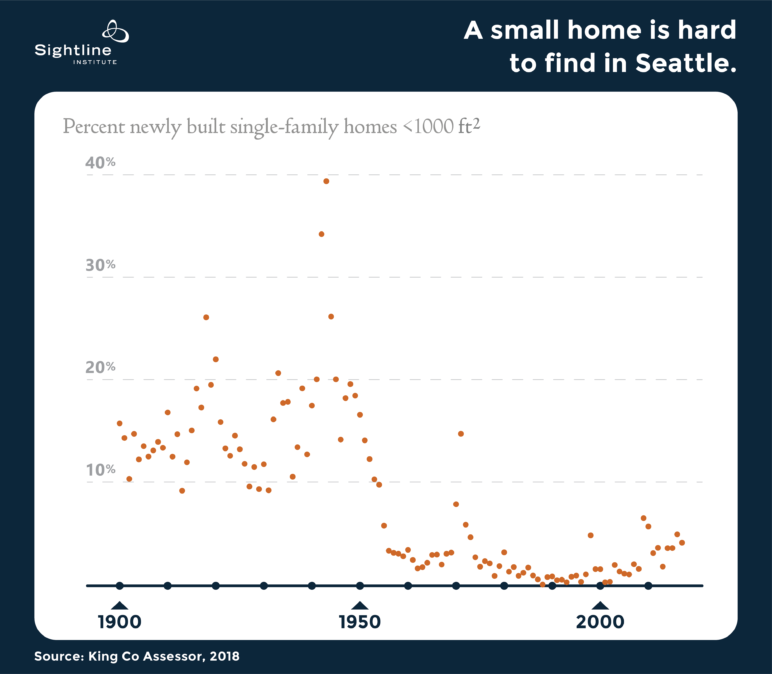

Unfortunately, small homes are a scarce commodity in much of Cascadia, and particularly in Seattle. Seattleites’ appetite for more space has steadily swelled since the 1950s and builders have accommodated, building larger homes every year since. Between 1900 and 1950, average new single-family home size in the Emerald City hovered below 2,000 square feet, with 16 percent of new homes measuring less than 1,000 square feet. This size diversity gave Seattle residents abundant small housing options.

Seattle’s average new single-family home size crossed the 2,000 square foot threshold in 1956, and it’s never looked back. Since then, builders have added an average of nearly 20 square feet per year to new homes. New home square footage shrunk slightly during the 2008 economic recession, but it has continued to hover just under 3,000 square feet since then. This is largely because builders have been constructing a larger share of Seattle’s new single-family homes on small, subdivided lots in the city’s multi-family zones. Though this constricts the maximum allowable home square footage, it is a response to many Seattleites’ continued hunger for four walls of their own.

As houses grow larger, the share of single-family homes under 1,000 square feet is shrinking dramatically: since 1956 builders have constructed just 3 percent of new single-family homes under the 1,000 square foot mark. And the squeeze over the last decade has been particularly fierce: Seattle has added fewer than 160 single-family homes under 1,000 square feet since 2008. This steady trend to supersize homes not only raises prices, but also slashes choice for households that want to go small for environmental, or personal reasons.

But even with that, Seattle has experienced a mini revival of smaller housing options since 2000, evident in the small post-2008 uptick in the chart above. In addition to the slightly increased selection of single-family homes under the 1,000 square foot mark added to Seattle’s housing stock over the last decade, the city has also seen a broader selection of small housing choices in other housing types. These include a shrinking average new apartment size (in 2017 the average size of a new construction apartment in Seattle was 635 square feet), nearly 300 new townhomes built under 1000 square feet, plus a net gain of 816 ADUs and DADUs (built between 2008 and 2016), and the short-lived revival of micro-apartments from 2009 to 2014.

ADUs offer a return to small and green

As Seattle’s stock of small home options in its single-family zones shrinks every year, so does its energy-smart housing stock. ADUs could change this, offering Cascadians interested in green housing more home choices in neighborhoods across the city. The climate benefits of ADUs accrue not only from their compact size, and attendant slashed heating, cooling, and lighting bills, but also from reductions in building materials. Attached accessory dwellings in particular, like basement apartments or above-garage units, can take advantage of existing materials and structures, thereby cutting energy costs from material manufacture, transport, and construction even further. In addition, most Cascadian cities, including Seattle, regulate ADU size to 1,000 square feet or less, even smaller than the small home the Oregon DEQ studied. This suggests the climate savings of an ADU compared to a medium sized new homes would be even greater than in the report.

Seattle can take simple steps to green its housing stock

Portland’s relaxation of its ADU regulation obstacle course shows that reducing policy barriers can in fact facilitate growth of this housing type. Since the city eliminated its ADU parking requirement and development fees in 2010, it’s seen annual ADU permits grow astronomically. In 2010 the city issued fewer than 100 ADU permits; in 2016 the city issued over 600 permits.

Seattle’s city council could do the same for Seattleites this year, growing the Emerald City’s green housing stock and giving more households the option to live green. Council members will have the opportunity to remove four specific barriers that hinder this green housing option: requirements for off-street parking and owner occupancy, the one accessory dwelling unit per lot limit, and restrictive construction mandates, including height, size, and setback standards.

Removing these building barriers and giving Seattle landowners the freedom to build accessory dwelling units as they please would help the Emerald City live up to its name, with abundant green housing options for its climate-conscious residents.

Methods

The energy consumption estimates for a medium sized newly built single-family home come from a 2010 Oregon Department of Environmental Quality report. This report calculated the lifetime energy consumption of a home close to the average market size for new homes in Oregon, built according to current industry standards and practices.

Comments are closed.