This article is a sequel to my previous publication about Seattle’s zoning history.

Wallingford, on Seattle’s near north side, could fool a passerby for a suburb, with its predominance of large single-family homes, few pedestrians, and quaint squeak of a commercial strip on a few blocks of its main drag on 45th Street.

In my previous article I provided a guided tour through Seattle’s last 120 years of city planning decisions, culminating in its current housing shortage. It’s a story of a myriad of seemingly tiny, innocuous choices—downzones, height restrictions, larger setback requirements, and escalating parking regulations—that together have strangled housing choice in the city, and inflamed prices to unprecedented levels. It’s a story, unfortunately, that’s typical of zoning history across Cascadia and beyond.

In this article, to make things even more concrete and specific, I’ll take a look at the history of a single Seattle neighborhood: Wallingford. Sightline profiled its housing history more extensively and visually in an earlier article, too, but here I highlight a few additional turning points, including how certain residents have taken an active part in that community’s evolution.

Erasing diversity: how Wallingford became single-family in two decades

Wallingford, on Seattle’s near north side, could fool a passerby for a suburb, with its predominance of large single-family homes, few pedestrians, and quaint squeak of a commercial strip on a few blocks of its main drag on 45th Street. If not for the nearby views of Lake Union and downtown Seattle, one might forget she was in a city at all. And a handful of folks in Wallingford have lobbied over time for precisely that effect.

But it wasn’t always this way. Much of the neighborhood fell within the 1923 second residence district (read about this zoning history in my previous article), permitting any type of multi-family dwelling, usually with a maximum height of 40 feet. As late as 1939, one in ten residential structures in Wallingford was a multi-family home. Duplexes, triplexes, rowhouses, and apartment buildings laced the neighborhood streets south of North 39th Street and west of Meridian Avenue.

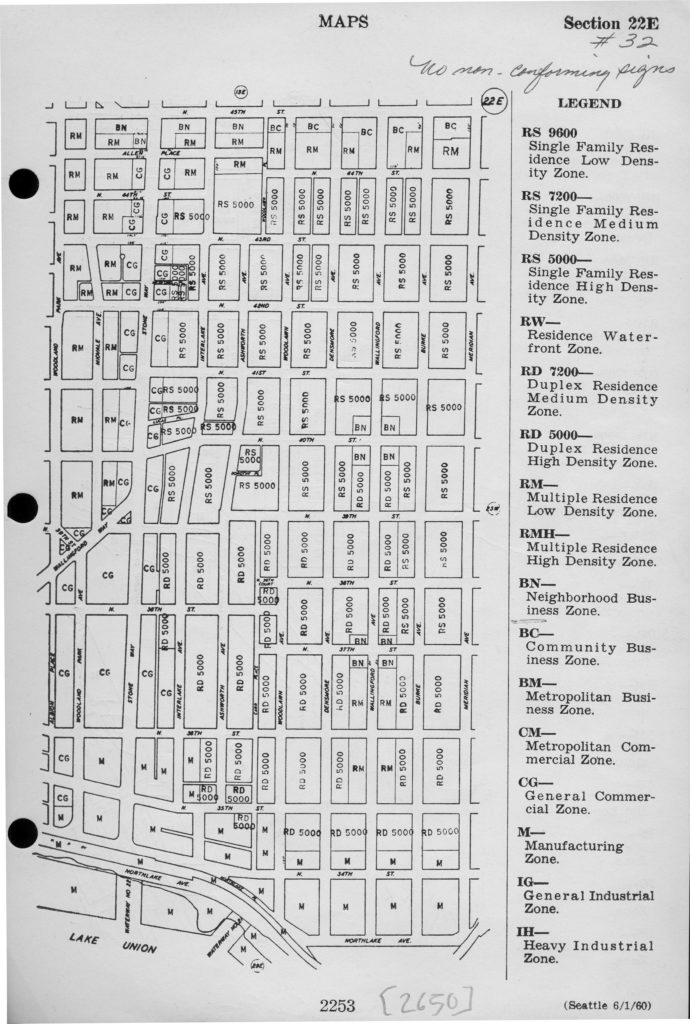

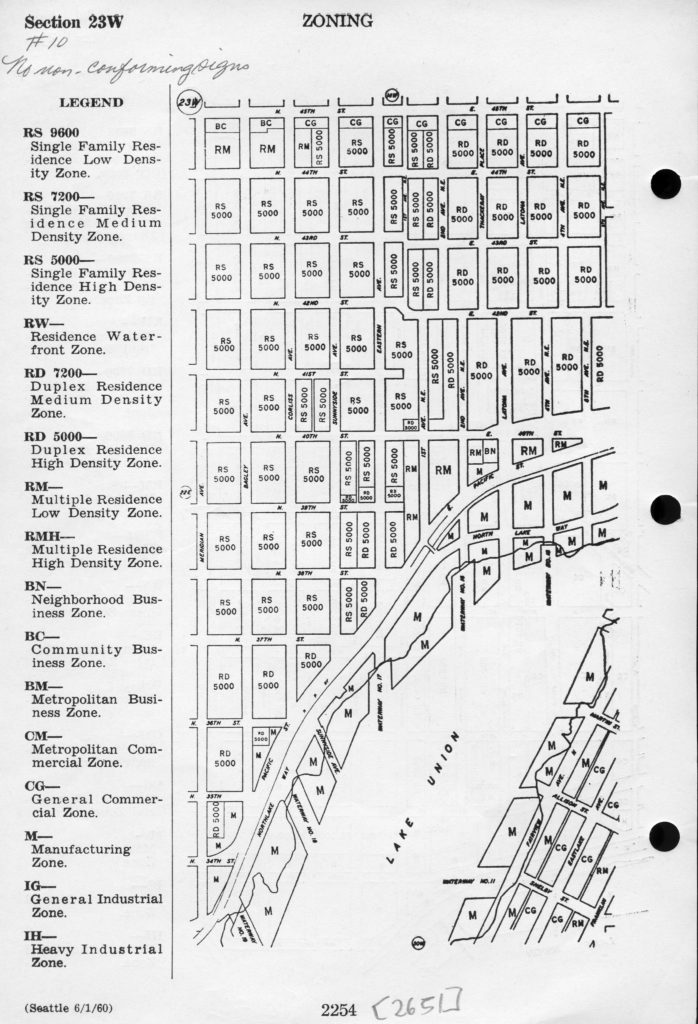

Between 1957 and 1960, the city downzoned large swaths of Seattle’s second residence districts, including those in Wallingford, to more restrictive zoning types. City planners took a pen to the Wallingford zoning map, slashing housing flexibility by downzoning most of the neighborhood’s second residence zones to a newly created residential duplex zone—a half-step between single- and multi-family zoning that permitted only single-family homes, duplexes, and a few triplexes—or the even more restrictive single-family zone.

By the early 1970s, the multi-family and duplex options of Wallingford were proving attractive to students and others affiliated with the nearby University of Washington, and some builders began buying local homes to convert into more of this in-demand housing type. Wallingford homeowners were not pleased: they organized themselves and successfully lobbied the city to further downzone the remaining duplex zones in their neighborhood to strictly single-family.

A small minority builds the neighborhood’s walls

Two decades later in the 1990s the City of Seattle began implementing its urban village strategy, intended to create pockets of density, and more housing options, in neighborhoods throughout the city. The city proposed urban village plans for several neighborhoods across the city and each neighborhood had a chance to submit its proposed amendments to the city’s plan. A select group of Wallingford residents, and especially members of the Wallingford Community Council (WCC), were the driving force behind shaping the Wallingford Neighborhood Plan. Their input focused, almost entirely, on restricting any type of housing beyond single-family homes to a small share of the neighborhood’s total area. Though the plan recommended adopting, and even slightly expanding, the city’s proposed urban village boundaries for the neighborhood, it placed enormous emphasis on making absolutely no changes to areas zoned single-family within the new urban village (see page 22), a land use that runs completely contradictory to the intended purpose of the villages. In addition, the neighborhood’s plan suggested the area may need a future downzone of some of the commercial land in the urban village (see pages 22-23). In other words, the neighborhood would accept the city’s urban village boundary proposal so long as it didn’t touch any single-family neighborhoods.

Notably, less than one percent of Wallingford’s population counted as “very active participants” in the community’s plan development process. This trend appears to continue in the neighborhood today. WCC’s board currently skews overwhelmingly to homeowners and has been accused of active prejudice against renters. It has come out vocally against the city’s Housing Affordability and Livability Agenda (HALA), even its modest moves to increase the diversity of housing options in Seattle, like allowing more ADUs. One of its board members even penned the argument against the city’s Housing Levy for the 2016 Voters Guide (which passed, and by its largest margin ever).

In short, in 60 years the neighborhood went from one that was open to housing the diversity of Seattle residents, to one of the most exclusive neighborhoods in the city, where the median single-family home is valued at just south of $1 million. The process, egged on by incumbent homeowner interests representing a minority of the neighborhood’s residents, came in the form of incremental downzones, setback increases, height reductions, parking requirements, and other measures. All of these are subtle but cruelly effective tools in developing and preserving exclusive communities, especially in the face of clearly increasing need for homes—of many types and sizes and price points—across a growing city.

Where to from here?

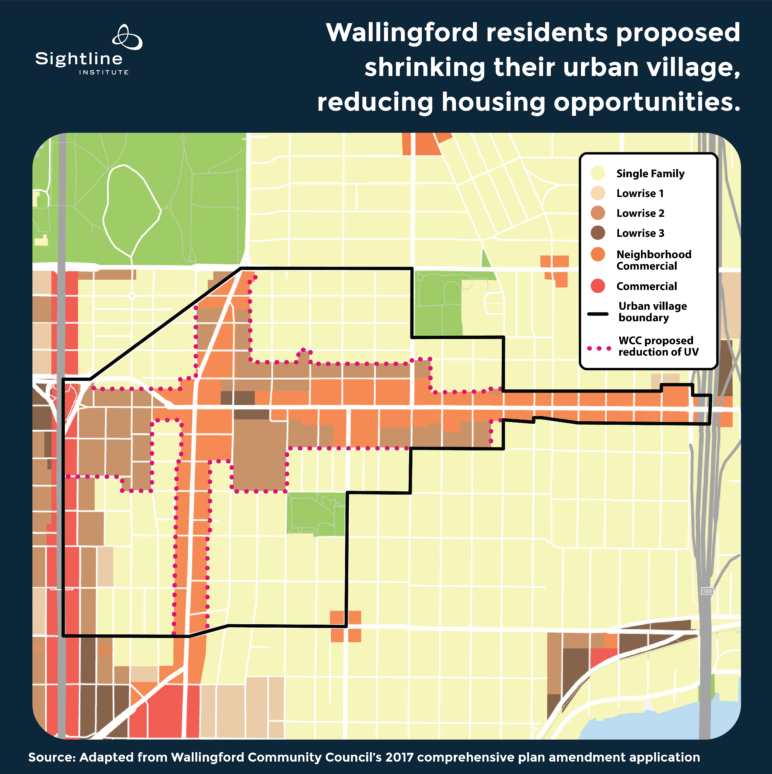

Just last year the WCC submitted a proposed amendment to Seattle’s Comprehensive Plan to remove fully half of the present urban village, safeguarding it as single-family zoning. In the map below, adapted from the WCC’s 2017 urban village amendment application, the red dotted line shows the WCC’s 2017 proposed new urban village boundary. Zoning colors show current zoning of the neighborhood, with light yellow indicating single-family zoning.

In effect, this proposal would shrink the existing urban village boundary, reducing the already constrained development capacity of the area, and creating more significant edge effects of single-family on denser multi-family zones. Two other Seattle neighborhoods submitted similar proposals in 2017 to shrink or downzone their urban villages, thereby minimizing any impacts from city-wide upzone plans: the West Seattle Junction (page 7), and the Morgan Junction neighborhood (page 295). These requests shouldn’t be surprising; they are history repeating itself: zoning restrictions lobbied for by a select few that confine the lives, space, and opportunities of countless people.

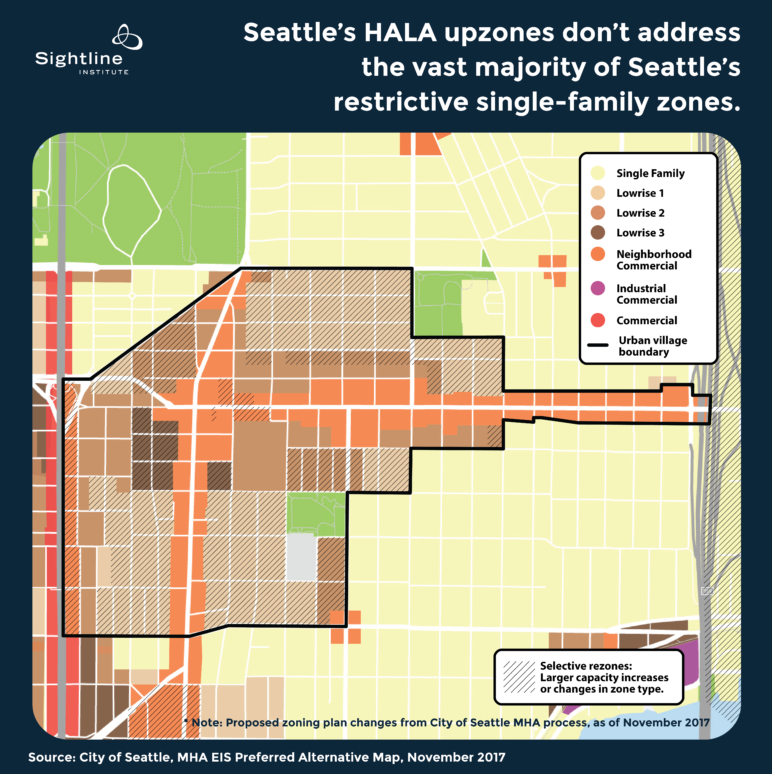

At present, Seattle’s Office of Planning and Community Development has not recommended that the city adopt these proposed amendments. But the city’s proposed zoning changes via HALA also don’t do much to restore the city’s once vibrant, flexible housing environment. For example, though the HALA plan proposes upzoning land within Wallingford’s existing urban village boundary to some of the more flexible zoning types for which these villages were intended (a two decade delayed fulfillment of the urban village plan), it does nothing to expand the village and continues to privilege the rest of the neighborhood as strictly single-family. In fact, the HALA plan leaves 94 percent of the city’s single-family zones entirely untouched.

The map below shows the city’s current proposed plan for upzoning Wallingford’s urban village. Though it includes significant upzones within the urban village—indicated by the hash marks—it leaves the vast majority of the neighborhood, everything outside the 1994 urban village boundary, untouched. Almost all of this land is zoned single-family, indicated by the light yellow shading, a land use scheme far less flexible than what used to exist in the neighborhood.

How to create a welcoming city

This is the profile of just one neighborhood, but it’s a pattern that has prevailed in many other areas of Seattle—and of other Cascadian cities—as well, resulting in month-over-month increases in home costs and rent, readily documented in countless local headlines.

As it stands now, the city’s zoning code is an exercise in opportunity hoarding: keeping the opportunities of Cascadia’s largest city available for only the lucky few who have been able to find—and afford—one of the limited spots in the city.

In Seattle, those opportunities range from attending world-class universities and colleges to perhaps finding one’s first $15-an-hour job; from joining a community where one might for the first time feel safe to express her true gender or sexuality to finding a new home and corresponding food and customs among fellow immigrants from one’s same home country; from going car-free and opting instead for Seattle’s expanding transit and bike-share options to learning a new outdoor sport or going camping for the first time within a short drive or bus ride from the city limits; from raising a family among a wealth of diverse neighbors and other families to visiting art and history museums or attending live music any night of the week.

Of course, those are just a handful of the opportunities that Seattle represents to those lucky enough to call it home. And when policies unreasonably restrict the kinds or numbers of homes permitted in the city’s neighborhoods, those policies restrict countless people—current residents and hopeful ones—from sharing in the wealth and potential of those opportunities.

HALA’s Mandatory Housing Affordability proposed upzones would produce a nominal increase in allowed development for thousands of units of affordable housing, but 94 percent of the city’s single family zones contribute nothing to MHA, a massive inequity. Instead, Seattle could should look to the flexibility and ingenuity of the pre-1923 land use code: one that required safety but allowed Seattleites to build the housing that suited them.

This article was adapted for Sightline Institute by Serena Larkin and Sightline senior research associate Margaret Morales from three original articles by Seattle dad, designer, and writer Mike Eliason. Find his originals here, here, and here, and find Mike on Twitter at @bruteforceblog.

Notes on Methods

To calculate the percentage of Wallingford zoned for single-family we used the city’s formula. This is equal to the total single-family parcel acres divided by total parcel acres in the neighborhood of all zones plus park acreage.

Comments are closed.