This article is Part 1 in my two-part series about Seattle’s zoning history and its impact on the city’s housing shortage today.

Though Seattle is Cascadia’s biggest city, its zoning history is a case study in the region’s larger pattern.

Picture yourself, nearly one hundred years ago, on a street in Seattle’s Wallingford neighborhood, years before Harland Bartholomew’s zoning ordinances began to change the landscape. Looking around and strolling through the area, you might see an abundant mix of residential building types within steps of each other: small apartment buildings near duplexes and triplexes, boarding and lodging houses on the same block as single-family homes. You would also see a mix of Seattleites living in those homes: seniors, families, singles, couples, perhaps going about their business on the main thoroughfares, stopping at the grocer or tailor, meeting friends at a local pub or restaurant, or enjoying picnics at the new Olmsted Brothers-designed park around Green Lake.

All of that is because, one hundred years ago, multi-family housing was legal to build anywhere in the city. A good thing, too: the city’s population grew from just over 80,000 in 1900 to more than 315,000 in 1920, nearly quadrupling in size in just two decades—with the housing needs to match. And places like Wallingford could offer a range of housing types to meet the diverse needs of the people and families moving to the city for its economic opportunities.

Today, as Seattle undergoes another population boom, that same neighborhood is not nearly so welcoming. Fully 70 percent of land there, excluding parks and rights of way, is reserved exclusively for single-family, detached homes, and the median one is valued at just shy of $1 million. The city’s current zoning code prohibits building smaller and more affordable options like ‘plexes, townhomes, and small apartment buildings—let alone boarding houses or dorms—on nearly every block in the area, even though such options could open up opportunities for people at a greater diversity of economic means to live in that sought-after neighborhood and enjoy its amenities, too. Worse, its local “community council” actively lobbies against these kinds of home options (more on that later).

Unfortunately, this is not a unique story. Though Seattle is Cascadia’s biggest city, its zoning history is a case study in the region’s larger pattern.

So what happened? How did Seattle go from being a place where home types welcomed newcomers to one that excludes all but those who can afford a near-million-dollar home? Well, it didn’t happen overnight. It was a slow-walk into this prohibitively expensive housing market, and it goes something like this…

The early days: Housing to meet a growing city’s needs

Prior to the city’s first zoning ordinance in 1923, what you could build in Seattle was outlined in a tidy fifty-one page building code first published in June of 1909. The city was already experiencing some of the above-mentioned growth, and with memories still fresh enough of Seattle’s Great Fire just twenty years earlier, it focused almost entirely on ensuring buildings complied with basic construction and safety standards (the words “fireproof” and “approved slow-burning construction” make conspicuous appearances throughout the document).

The 1909 building code defined seven building classes (A-G) based on construction and fireproofing standards. Class A buildings had the most stringent safety requirements and could also be the tallest (up to 200 feet); Class G buildings generally had the least rigorous construction and building material standards and could reach a max of only 40 feet.

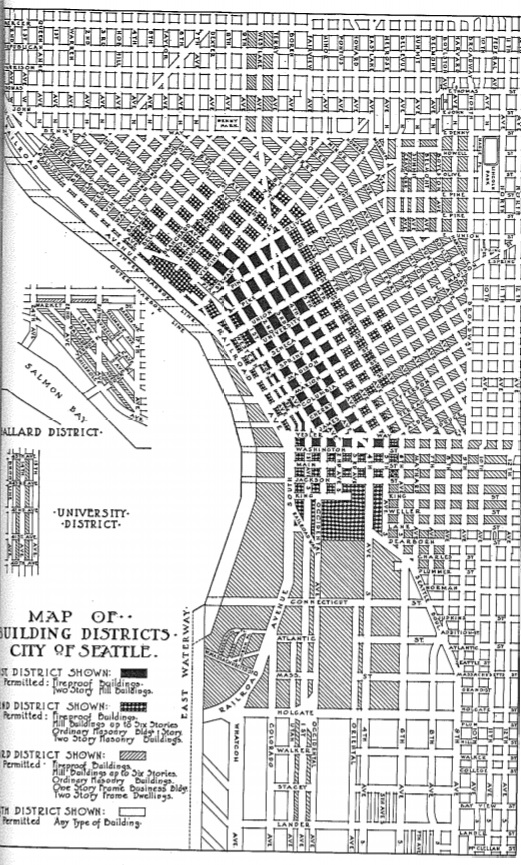

The code also divided the city into four building districts, concentric rings emanating from the center of the city’s downtown core. The city permitted only buildings with the highest fireproofing standards and allowable height limits (Classes A-C) in the downtown core, while districts farther from the core could also include buildings in the lower classes, those that were shorter and had fewer fireproofing and structural requirements.

The smallest dwelling unit the code regulated was “a building designed and used only for the residence of not over two separate and distinct families” [my emphasis]. In other words, it didn’t even mention the concept of a single-family dwelling. Beyond that, the code defined an enviable variety of other home types, all multi-family, including the apartment house, flat building, and lodging, boarding, and tenement houses.

Eight years later in 1917, the city updated the code, slightly changing the building district boundaries emanating from downtown and consolidating the seven building classes into four: fireproof, mill, ordinary masonry, and frame buildings.But generally the same city design principles outlined in the 1909 code stood: the city permitted only buildings with the tallest height limits and most extensive fireproofing requirements in the downtown core, and allowed a gradually greater mix of buildings in districts emanating from there.

Allowable lot coverage for all building types varied from 73 to 100 percent. Apartment buildings could even omit yards if residents could recreate them on the roof. (Today’s low-rise zone setback standards of 5 to 7 feet to the front and per side, and a 10-foot rear minimum compare miserably; single-family zone setbacks are even more stringent, with a typical 20-foot required front yard setback, 10-foot rear setback, and 5 feet per side.)

But most interesting for today’s readers, perhaps, is that there were no restrictions on where different kinds of homes could be located. This included apartment buildings, flats, family residences or dwellings, boarding and lodging houses, dormitories, hotels, and clubs, and it’s why many of Seattle’s present-day single family zones include duplexes, triplexes, and apartment buildings. There simply was no single-family zoning, so you easily could have had a small apartment building beside a detached home.

In other words, by present-day standards, none of Seattle was zoned less than Lowrise 3. That is, it could include any type of home under 40 feet in height, from a single-family house to a duplex, from a townhouse to a small apartment building. And of course, much of the city—particularly land closer to the downtown core—permitted buildings much larger than that. This was the kind of code that told the world: Seattle is ready to grow into a world-class city, and we’ll build all the kinds of homes it takes to house the workforce that will get us there.

Harland Bartholomew and the codification of segregation

Well, that didn’t last. Just six years later in 1923, Seattle would implement its very first zoning ordinance, compliments of one Harland Bartholomew, the chief planner of St. Louis, Missouri. Bartholomew’s office worked on comprehensive plans for hundreds of cities across North America, including Vancouver, BC, and many others on the West Coast that today are dominated by exclusive single-family zoning, sprawl, and severe housing shortages. He was also an early car-head, including wide boulevards in his plans in order to privilege commuters driving into cities from their homes in the suburbs.

Woven through these designs was a more pernicious priority, represented in the goal Bartholomew stated for his 1919 St. Louis plan to “preserv[e] the more desirable residential neighborhoods” and to block movement into “finer residential districts… by colored people.” Of his 1922 plan for Memphis, Tennessee, historian Roger Biles notes that:

While it sought to demarcate areas of industry, commerce, and residence, the ordinance additionally reflected the desire of the elite to maintain existing patterns of racial segregation…. Recognizing that these informal boundaries might shift or that a growing black population might spill over into heretofore white neighborhoods, the strict application of zoning laws, particularly having to do with dwelling standards, went a long way toward preserving the exclusivity of white enclaves.

1923: Seattle, meet single-family zoning

Seattle’s new zoning code brought with it some major changes in how the city thought about building and design. As we’ve written about before, Bartholomew’s zoning ordinance was one of sweeping downzones and initiated a slow strangulation of Seattle’s housing options, setting the city on a crash course with today’s acute housing shortage. The 1923 plan differed from the previous codes in that it shifted the focus from safety and construction requirements to regulations on building uses across town. As a part of this, it mentioned the concept of a single-family, detached home (an idea absent in the previous building codes), and introduced the first single-family zoning restrictions Seattle had ever seen—outlawing multi-family housing in about 46 percent of the city, excluding parks and rights of way. It also codified the city’s first blanket height restrictions. The previous building code had worked to discourage smaller buildings in the city’s downtown core but permitted larger buildings anywhere in the city; this zoning code brought with it the first outlawing of height across most of the city.

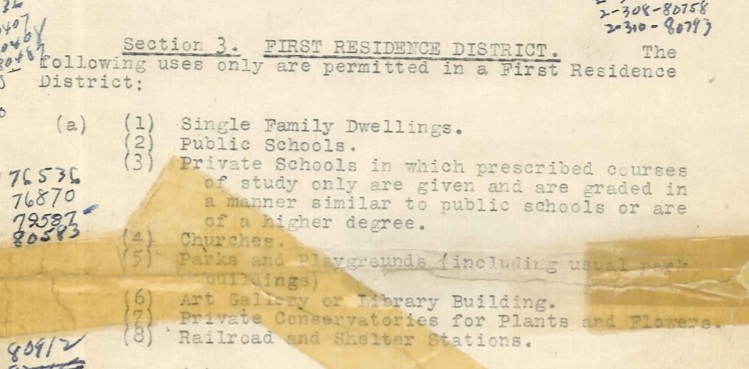

With the new focus on use, rather than safety, the code scrapped the previous building districts and instead divided the city into six use districts: first and second residence districts, business, commercial, manufacturing, and industrial.

- The first residence district allowed single-family dwellings, public and private schools, churches, parks, art galleries, libraries, plant conservatories, and rail stations (this last likely to accommodate the trolley that then connected different parts of the city). Boarding houses were also legal here, if supervised by a corresponding institution (like a school). This zone was the slightly more flexible ancestor of today’s single-family zone.

- The second residence district permitted: any use permitted in the first district (likely why there are so many single-family houses on low-rise-zoned lots), plus any other type of multi-family housing including flats, apartment buildings, boarding and lodging houses, and hotels.

- The business district permitted what was allowed in first and second residence districts, plus stores, offices, banks, restaurants, theaters, laundries, garages, and other establishments (see the full 1923 ordinance if you’re curious for more).

The remaining commercial, manufacturing, and industrial districts all permitted any of the prior districts’ uses—so, technically, these districts could host any type of residence, even if that wasn’t common.

Overlaid across the city’s new use districts, Bartholomew’s ordinance established five height districts, the first blanket caps on height for reasons other than structural integrity: 40 feet (or 3 full stories), 65 feet, 80 feet, 100 feet, and “maximum height.” Most of the first, and much of the second, residence districts were capped at that lowest limit of 40 feet (again, today’s limit for single-family zones is 35 feet, and just 30 if built with a flat roof).

Finally, Bartholomew’s 1923 plan also split Seattle into four area districts designated A through D to restrict lot coverage and setbacks. Most of the single-family-zoned land now fell within District A, which had a lot coverage maximum of just 35 percent (still in effect to this day), or 45 percent for corner lots—a stark decrease from pre-1923 standards of 73 to 100 percent.

Despite all this, the 1923 district maps still permitted multi-family housing across a great deal of Seattle as compared with today’s zoning code. In particular, the plan committed significant portions of the Central District, Wallingford, and West Woodland, as well as bits of Magnolia and West Seattle, to multi-family housing via second residence districts. In all of these areas, one can still find multi-family homes that were built during this period. Since then, each of these neighborhoods have downzoned their multi-family areas, outlawing all housing types save single-family homes. I’ll explore Wallingford’s walk through its downzoning history in my next article.

The continued strangulation of housing choice

Over the subsequent decades of the twentieth century, apart from a stretch from about 1960–1980, Seattle would continue to grow in population, sometimes faster, sometimes more slowly. But its laws around homebuilding did the opposite, instead growing more restrictive with each new iteration of the city’s zoning ordinance.

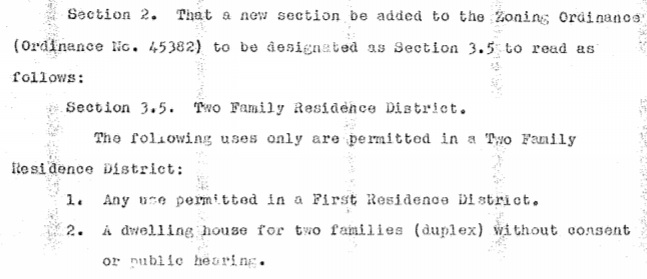

For instance, in 1947 the city further segregated residential uses by splitting the 1923 plan’s “second residence district” into two new classes: the “two family district” and “second residence district.” This new two-family district created a half-step between the city’s multi- and single-family areas, and with it a path for incrementally downzoning swaths of Seattle’s multi-family areas. Residents and city officials would take advantage of this incremental step in the coming decades, slowly downzoning pieces of multi-family zones to the duplex-triplex zone (as it came to be known). From there almost all of this land was gradually downzoned to single-family until the city did away with the duplex-triplex zone in 2011.

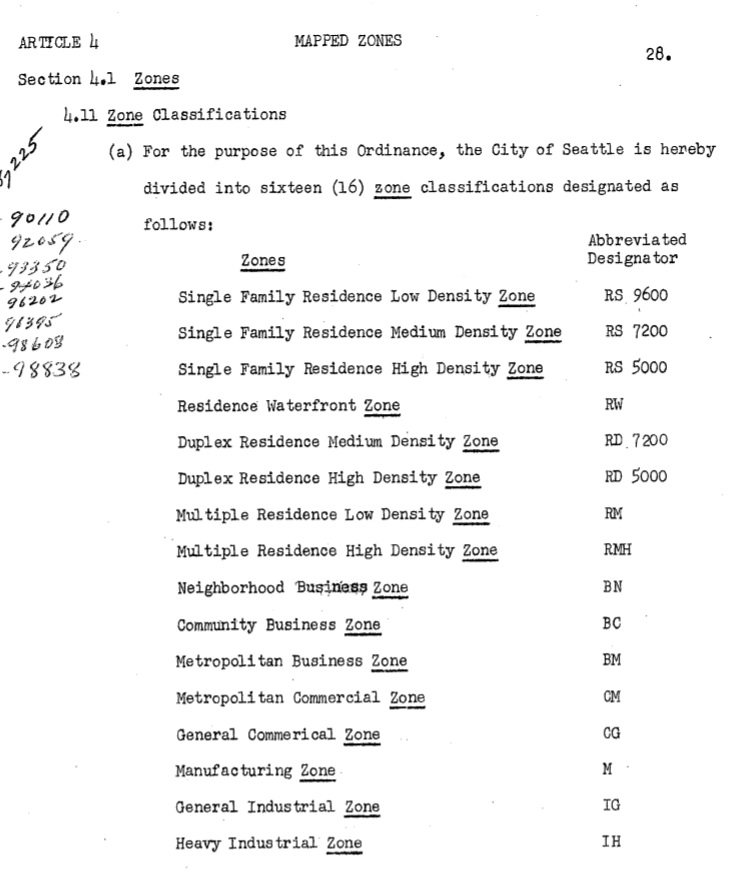

Come 1957, a new plan would restrict vast additional tracts of multi-family land in Seattle to single-family and further stratify both single-family and multi-family dwellings. This is where today’s “SF5000,” “SF7200,” and “SF9600” originated: that is, the zone designations for a minimum lot area, in square feet, in single-family zones. In short, in under 35 years, Seattle went from supporting all kinds of housing across the entire city to fully 8 segregated residential categories, with multi-family housing options outlawed in over half of the city.

Subsequent iterations of the Comprehensive Plan would continue to restrict the kinds of homes that could be built across Seattle—and hence, the kinds of people that could afford to live there. The 1990s would see a gerrymandering of low-rise development into a series of “urban villages” that concentrated multi-family housing options on a few small slivers of land peppered about the city. Interestingly, much of the land in urban villages today remains zoned single-family, and therefore not living up to the intention of the village strategy.

As for vehicle parking, the 1923 zoning ordinance mentioned nothing of it, but the issue would creep into the city’s planning rules beginning in the 1970s and ‘80s. By the 1990s, parking paranoia would show up big-time in Seattle’s planning priorities. For example, the city’s 1995 code contained an eight-page list of parking requirements for fully 118 building types and businesses, ranging from sewage treatment plants to swimming pools, museums to mini-golf courses, plus another eight pages of text describing nuances in parking regulations.

One year later in 1996, Seattle took one step forward for affordable housing options and made its first allowance for attached accessory dwelling units (ADUs, a.k.a. “backyard cottages” or “granny flats”). However, it also required each new mini-home to have its own off-street parking space in addition to the one for the main house, making ADUs effectively impossible to build on many single-family parcels across the city.

Combined with more downzones, increased setbacks, and reduced height limits, parking requirements helped to eliminate many of the more affordable multi-family housing options in the city. They also added to the cost of what housing could be built, increasing rent across the city.

As for vehicle parking, the 1923 zoning ordinance mentioned nothing of it, but the issue would creep into the city’s planning rules beginning in the 1970s and ‘80s. By the 1990s, parking paranoia would show up big-time in Seattle’s planning priorities. For example, the city’s 1995 code contained an eight-page list of parking requirements for 118 building types and businesses, ranging from sewage treatment plants to swimming pools, museums to mini-golf courses, plus another eight pages of text describing nuances in parking regulations.

Moving beyond Bartholomew’s plan

This is a counter-intuitive history: a growing city with increasingly strangled housing options. Today over half of Seattle is reserved exclusively for single-family, detached homes (plus ADUs, though policy barriers to those are so high that their addition to the city’s housing scene has been glacial). Today’s zoning code restrictions on housing development are a far cry from the city’s flexible approach to housing in the early 20th century. Growing population coupled with squelched housing choices is not a recipe that works, though it’s one that has played out not just in Seattle, but across the region, though it’s one that has played out not just in Seattle, but across the region. AndAs a result, the city, and increasingly larger swaths of all of Cascadia,, and increasingly larger swaths of all of Cascadia, now has the housing prices to prove it.

It’s no surprise that today’s conversations about Seattle’s future are so heated. Many don’t understand or don’t want to take responsibility for addressing the above history as to how the city got to where it is today. Others—especially communities of color, immigrants, and families with lower incomes—know it all too well, whether in current patterns of gentrification or in historic exclusion from homeownership and resulting wealth-building in so-called “desirable” neighborhoods.

The fact is that Seattle’s housing crisis is self-inflicted, and indeed was crafted by a minority of mostly white, male planners, profiteers, and politicians. It directly results from land (ab)use patterns and their embedded racism and classism, but ignorance and denial of this are making slow, painful going of rectifying these wrongs. For example, the HALA recommendations, a rich suite of tools to help build the homes we desperately need, were besmirched in the city’s biggest newspaper before they even saw the light of day, stoking a fire under those who would prefer to forget that they live in a city, a place meant to change and grow, and in so doing offer to more people the opportunities it represents.

In short, the Bartholomew plan is alive and well in Seattle in 2018. It has more pages, new language, new faces and names involved, but it is still indisputably accomplishing the exclusion and proscriptions desired by a small, disproportionately influential group of residents—and it is holding Seattle back from the city it could be.

It’s time to bury Bartholomew and his backwards planning priorities. It’s time to answer the housing needs of our growing twenty-first-century city with an honest reckoning of the past and an ambitious, inclusive vision for the future. And it’s time to build into the very wood, bricks, steel, cement, and design of Seattle the diversity and equity to which Cascadia aspires.

In part two, I’ll explore this history in one specific Seattle neighborhood: Wallingford and examine where things are headed in that neighborhood today.

This article was adapted for Sightline Institute by Serena Larkin and Sightline senior research associate Margaret Morales from three original articles by Seattle dad, designer, and writer Mike Eliason. Find his originals here, here, and here, and find Mike on Twitter at @bruteforceblog.

Comments are closed.