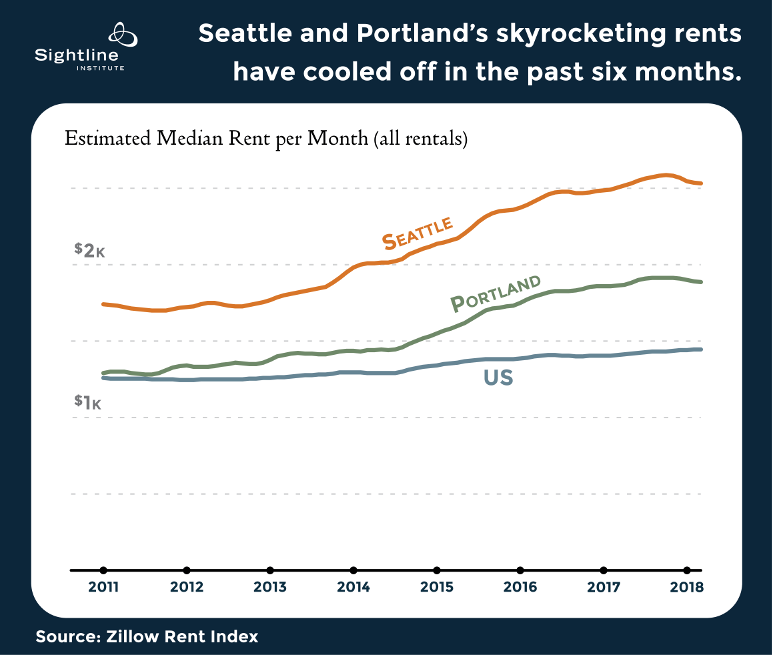

Cascadian sister cities Portland and Seattle have achieved the dubious distinction in recent years of consistently ranking at or near the top of major US metros for escalating rents. Over the past year, though, rent growth cooled in both cities, and in recent months median rents have actually declined.

Why? The main reason is builders in those cities constructed a lot of new apartments, and that made room for the deluge of people flocking to the two desirable metros and their booming economies. As more rental homes became available, competition eased, and so did rents.

The catch is homebuilding stalls if rents sink too far, because at some point rental income no longer covers the cost of constructing and operating apartments. In other words, building apartments becomes a money losing proposition. And then the disrupted flow of new homes curtails the decline of rents.

Here’s the opportunity: lower the cost of homebuilding and rents will fall further before builders pull back.

But here’s the opportunity: lower the cost of homebuilding and rents will fall further before builders pull back. Citywide average rent will reset to a lower baseline. And that’s a win for affordability. First, it means fewer struggling renters displaced by rising rent. (US Census data indicate that the number of Seattle homes renting for less than $1,000 per month declined by roughly 7,000 during 2014 when median rent rose by 8 percent.) Second, it means less public funding necessary to subsidize the smaller number of people who still can’t afford what’s available in the private housing market.

The go/no-go decision on every proposed housing construction project comes down to a comparison of the cost to put up the new building with the net income the building will generate from rent. Any cost reduction helps tip the scales toward “go.” Conversely, even a small added expense can be the proverbial straw that breaks the project’s back. And when new homes are sacrificed in a city with a shortage, low-income people bear the brunt of it, getting outbid for existing homes by those with fatter wallets.

What can policymakers do to minimize the regulatory costs they inflict on homebuilding and thereby also minimize their city’s average rent baseline? The main cost contributors are construction, financing, and land—factors largely outside the influence of public policy (see endnote below on land values and zoning). Cities do, however, control rules and fees.

Previous Sightline articles have described the damage to affordability caused by fees and permitting delay, and more specifically by environmental review, design review, historic preservation, impact fees, and parking quotas. I also published a series of articles critiquing Seattle’s Mandatory Housing Affordability program (Seattle’s version of inclusionary zoning) because it will likely impose net cost in many cases and undermine its own intent (here, here, here, here).

So yes, cities can do a lot on the regulatory cost front to help affordability. Why aren’t they?

Muddled thinking begets costly regulations

One major roadblock to cost-reducing policy changes is the commonly held but misguided presumption that homebuilding is somehow disconnected from economics, that added regulatory costs have no consequences. Some rationalize it like this: if a city relaxes a regulation to reduce cost, developers will just charge whatever rent the market will bear anyway and pocket more profit. But that argument ignores a key factor: lowering costs accelerates homebuilding, which over time reduces what the market will bear. What matters is the long-term, rent-softening effect on the whole housing system, not the isolated instance.

Others posit a more nuanced, yet also flawed rationale that goes like this: if a new regulation adds cost, housing developers compensate by offering less for land on which to build (true), but landowners will sell just the same at the lower price (not true), so the homes still get built, no harm done. For the gory details on why that’s not true look here and here. Or for a shorter take, ponder this scenario:

You own a rental house and are considering redeveloping it into four townhouses. The city adopts a new regulation that adds $100,000 to your project cost that you will be forced to eat up front if you proceed. The guaranteed cash flow from the existing house now looks like the better option. If instead you were thinking about selling the property, a developer would offer you $100,000 less. Likewise, holding on to the house now seems like the best choice. Either way it becomes more likely that no new homes get built.

In San Francisco this kind of sloppy, wishful thinking about development economics has led to the present quagmire in which the city charges upwards of $100,000 in fees—per apartment unit!—and the permitting process can devour four years even for uncontroversial projects. These hurdles have helped boost the typical cost of developing a single apartment to a whopping $700,000, about twice what it costs in Seattle. No surprise that San Francisco’s median rent is nearly double Seattle’s.

It really is this simple: if we make it more expensive to build homes, homes will be more expensive. Any regulation that raises homebuilding cost is a tradeoff with affordability. Some—such as fire codes and structural requirements—are worth the tradeoff, obviously. But in cities facing ballooning rents caused by a shortage of homes, the onus is on regulators to be exceedingly judicious. For example, are rules that invite frivolous appeals of homebuilding projects worth the higher rents they will inevitably cause citywide? And lest we forget: getting rid of bad regulations or fees is often more difficult than adopting them in the first place.

Consulting the crystal ball for rents in Seattle and Portland

What does the future look like for Seattle and Portland? The Seattle metro has record numbers of new apartments in the pipeline over the next couple of years, which bodes well for continued slackening of rents. However, if adopted as planned this Fall, Mandatory Housing Affordability will most likely put the chill on some future homebuilding and create upward pressure on Seattle’s average rent baseline. Same goes for impact fees, for which some Seattle elected officials are advocating.

In contrast, Portland’s rental housing permitting pipeline has all but dried up over the past year. The slowdown was probably caused in part by new inclusionary zoning requirements that impose net costs on homebuilding, though it’s too soon to be sure. In any case, it doesn’t bode well for ongoing easing of rents over the coming years.

Seattle and Portland each pulled off an extraordinary feat: they built enough new homes to calm the rent explosion, even as their economies continue to expand and draw newcomers seeking good jobs. They can keep that successful run going longer and push rents even lower by eliminating homebuilding fees and red tape. Every little bit helps and policymakers can do all sorts of things, such as those described in the Sightline articles cited above, or see, for example, multiple recommendations in Seattle’s Housing Affordability and Livability Agenda. The lower a city’s average rent baseline falls, the better off all renters will be, and the further limited public funds will go toward subsidizing homes for those who need it most.

Endnote: Land values and zoning

While city governments can’t directly control the price of land, they do set zoning, which has a complicated relationship with land values. When zoning restricts the number of homes that can be built in a city with a shortage, it drives up rents and that raises the price of land. If a change to zoning allows a larger project with more apartments in it, that project will generate more rent, which makes it more valuable (in most cases). In the near term that puts upward pressure on the price of the land, while over the longer term, the boosted number of new homes built citywide under the relaxed zoning puts downward pressure on rents and land values.

However, what matters in determining rent is the cost of land per home. Even when the price per square foot of a parcel of land goes up under a zoning change that allows more apartments on it, the cost of land per apartment usually ends up lower. Less rent required per home to cover land cost means homebuilding is financially feasible at lower rent. In sum, cities can indirectly reduce the impact of the cost of land on rent by upzoning.

Comments are closed.