Author’s note: Jameson Quinn and Jack Santucci have pointed out this method was proposed in 1884 as “The Gove Method.”

Here at Sightline, we’re fans of proportional representation, including multi-winner ranked-choice voting. We recently conducted focus groups to find out what voters in Oregon and Washington think about proportional representation. (Sightline director of strategic communications Anna Fahey will write more about these focus groups soon.) Overall, we found out that voters across the ideological spectrum:

1) think we need to change our broken systems,

2) like the idea of proportional representation, but

3) don’t like the methods for getting there.

They don’t like party list methods because: parties. And they don’t like ranked-choice methods for two reasons. These two reasons are the key political problems with getting ranked-choice voting (RCV) implemented. First, voters perceive RCV ballots as more complicated than “pick one” ballots—which they are, though not so much that voters do not easily master them when a jurisdiction switches to RCV, as Sightline’s Margaret Morales will write about soon. Second, to make the most of an RCV ballot, voters must be more knowledgeable. They don’t just pick one favorite; they can rank all or several of the candidates. This perception is also true, and it becomes more true in multi-winner races with more candidates on the ballot for voters to parse. Again, though, the vast majority of voters quickly adapt to RCV ballots and fill them out adequately, as Margaret will write about.

To adopt RCV in most Cascadian jurisdictions would require a vote of the people, so these perceptions could be deal breakers for the entire system. To overcome them, reformers might adopt two strategies. The first is to educate voters enough that their perceptions change and they support proportional representation—probably in its RCV form, because our focus groups were either split on or opposed to party lists. The second is to actually solve the problems with RCV: to make a voting system with a ballot that is simple and in which voters do not need to be more knowledgeable than they do under Cascadia’s prevailing “pick one” electoral method.

In most of my work, I’ve focused on the former of these two strategies: educating voters. But the focus groups made me think long and hard about the latter option. Is there a way to use a simple and familiar ballot to achieve proportional results?

Well, eureka! I’ve landed on something that fits the bill. Today, I am describing it and asking for your reactions.

The answer is a hybrid of “pick one” and ranked-choice voting. Or rather, it’s a way to get proportional results from a pick-one ballot. Let’s call it “delegated ranked-choice voting.” In delegated ranked-choice, voters choose their favorite candidate, but they do not rank the others. Therefore, voters don’t need to study all the candidates and figure out who is third and fourth and fifth—just pick their favorite, as they’re use to doing. Then, the candidates themselves rank-order all the other candidates and publish the list before the election. Each eliminated candidate’s votes transfer according to his or her published preferences. Voila! Proportional results from a “pick one” ballot.

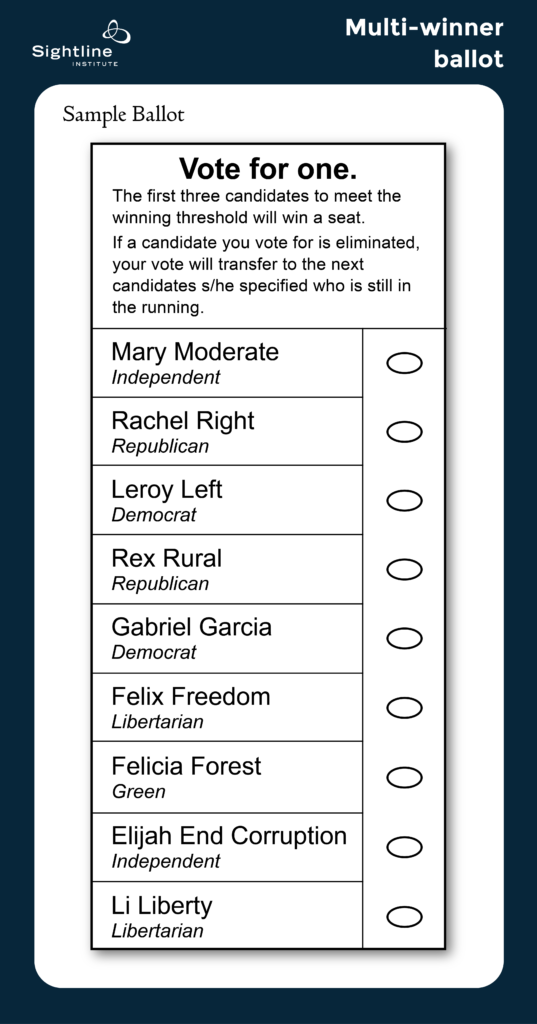

For example, imagine a three-winner Washington state legislative district with the fictional candidates on the sample ballot below. Your ballot looks exactly like it does now and you only have to pick one candidate, but you are free to choose your favorite even if he is not a front-runner, confident that you won’t waste your vote or spoil the race. You vote for Elijah End Corruption, but he gets the fewest number of votes—just 6 percent—and is eliminated. His votes transfer to the candidate he considered to be closest to him and whom he rank-ordered first—Mary Moderate. She already had 20 percent, so with Elijah’s transferred votes she passes the 25 percent threshold of exclusion for a three-winner district and wins one of the three seats.

What it would mean for voters, compared with the current pick-one system

Compared with the current system of voting in most parts of Cascadia, voters’ ballots would be simple and familiar. You would only have to know your one favorite candidate. Even if you didn’t have time to research all the candidates or check all of their rank-ordered lists, if you know that Mary Moderate shares your values, you can trust she will transfer your vote to another candidate who shares your values. After all, who knows the other candidates better than Mary? She’s been debating them at forums and interviews for months.

Additionally, you would not have to strategize about whom to vote for based on how they are doing in the polls, because your vote would still have a chance to count even if your favorite got eliminated (meaning that all her votes would transfer to her preferred candidate who is still in the race) or even if she didn’t need your vote because she won in a landslide (meaning that her excess votes would transfer to her preferred candidate).

Finally, you would know that your vote for a minor-party candidate would give that candidate power in the election, even if he didn’t win. In other words, you get all the benefits of ranked-choice voting; you just don’t have to know as much. How would you feel, as a voter, with elections run in this way?

What it would mean for voters, compared to an RCV system

The upside of delegated RCV compared to regular RCV is the delegation: many voters do not know enough to rank all the candidates with confidence (as in regular RCV), and they might not trust a political party to transfer their vote to someone else in the party (as in Party List), but they might trust their favorite candidate to rank her competitors. The downside is also the delegation: compared with regular RCV, delegated RCV ties the hands of those voters who know exactly what they think about multiple candidates.

Imagine the 2016 US presidential election used delegated ranked-choice voting. You voted for Sanders, and he ranked Hillary as his first alternate. So, when Sanders was eliminated after the first round, your vote was transferred to Clinton. Now, if you thought that was fine, then delegated ranked-choice worked well—you picked your true favorite, and your vote still counted in the final round. But if you were one of the US voters who liked Bernie Sanders best and Donald Trump second, then you would not be happy about your vote transferring to Hillary Clinton, your least favorite candidate. In short, the upside for less-informed voters is a downside for super-informed voters, and the tradeoff seems inherent in the system. Is it a tradeoff worth making?

What it would mean for candidates

Just like in ranked-choice elections (and unlike the current predominant system in Cascadia), candidates would have an incentive to run positive, issue-oriented campaigns rather than negative campaigns. If they made their lists public before the election, candidates would likely negotiate with other candidates to form alliances during the campaign.

And just like in RCV, minor-party or independent candidates would not be shut out of elections. They could run because voters could vote for them without fear of wasting a vote. And even if a minor-party candidate didn’t have quite enough support to win a seat, she could still influence a more mainstream candidate’s agenda by insisting he commit to certain policies or principles before she would agree to rank him.

Variations: How many votes do you get?

In the simplest version, which I’ve been discussing so far, voters get just one vote so the ballot looks just like a plurality ballot. But some variants are also possible, and I’d love to hear your thoughts on them in the comments section at the end of the article.

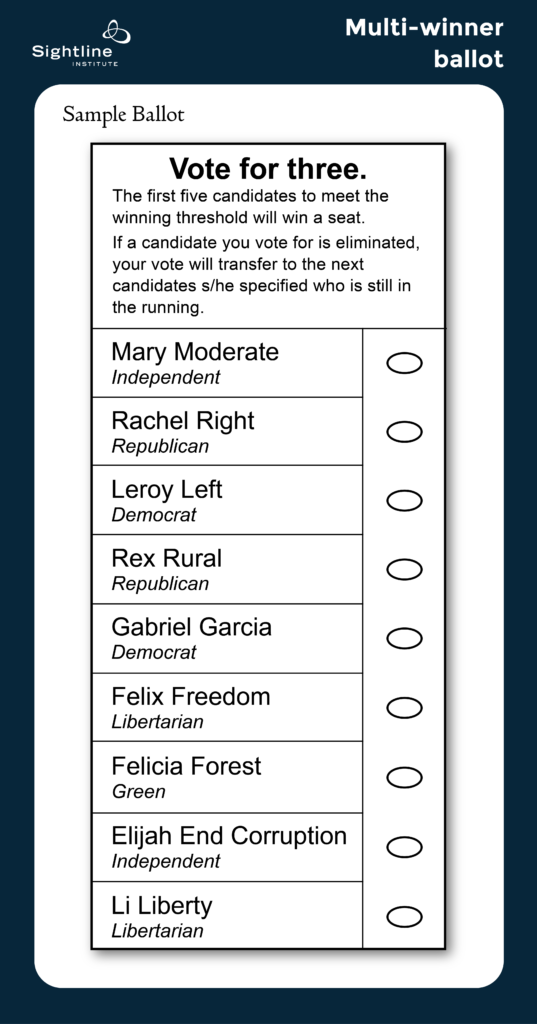

In a multi-winner race, say, a five-winner district, you might be disgruntled to have to pick just one. Instead, you could get, say, three votes—not an overwhelming number, but enough to empower you to express your preferences. The ballot might look like the one below. Many Oregon voters already have a ballot that says “Vote for Three” in city races so this would be a familiar ballot for some Cascadians. Alternatively, you could get the same number of votes as there are seats available, so in a five-winner district, each voter would get five votes.

Using seven votes in one race could be overwhelming for some voters, but their options could be simplified by counting the ballot like Equal & Even Cumulative Voting (used in Peoria, Illinois): if a voter had three votes but only filled in one bubble for Mary, all three of her votes would go to Mary. (If that sounds like it is violating the principle of one person one vote, you can think of it as each voter has one vote but is allowed to split the vote three ways or just cast it all at once for one candidate.) If Mary got eliminated, all three of her votes (or her one entire vote) would transfer to Mary’s top-ranked candidate who is still in the running. It’s an elegant approach that ensures all voters have equal power, even if some voters feel strongly about one candidate or aren’t familiar with more candidates or just didn’t realize they could fill in more bubbles. What do you think about using this method?

Another possibility: use a ranked ballot and voters could rank if they want to. If their rankings are exhausted (all their ranked candidates get eliminated) then it switches to a delegated ballot, and their vote gets transferred based on their last-ranked candidate’s preferences. This would take away the benefit of the simple, familiar ballot. But perhaps the ballot could be limited to three rankings rather than enough to rank all candidates, so it would be simpler than it might otherwise be while still ensuring your vote would count even if your top three choices are all eliminated. It could go along with an education campaign letting people know they truly only have to rank one candidate and their vote will still count. It shifts the tradeoff towards the high-information voters. What do you think about that?

More variations: How do candidates indicate their preference order?

My main idea is that candidates would publicly list their respective rank-orderings of candidates ahead of the election so that voters could see them. This approach offers several advantages. A super-informed voter could check to make sure he agrees with Mary’s choices for transferring his votes. A candidate’s ordered list could give that voter more information about how closely aligned she is with his interests, based on how high up on her list his other favorite candidates appear. Also, the votes could all be transferred and counted immediately after the election.

A second option is to allow candidates to use their votes to negotiate amongst themselves after the election. Electoral theorists Charles Dodgson (a.k.a. Lewis Carroll), Warren Smith, and Forest Simmons have all proposed this method, called Asset Voting, where each candidate uses his votes to horse-trade with other candidates after the election. For example, a candidate with a significant block of votes might exchange them for a promise that he will be appointed to a position he wants.

My guess is that Cascadian voters would balk at the idea of handing over their votes for politicians to barter with and would reject a system where they perceived politicians were choosing each other instead of voters deciding, but who knows? This method would also delay election results as candidates would need time to negotiate after the votes were in. Which of these approaches seems smarter to you?

What do you think?

Electoral reform will probably have to come from a vote of the people, since elected officials are usually loathe to change the rules that got them elected. Proposed reforms, therefore, need to appeal to a majority of voters. Party-based proportional representation definitely doesn’t. And ranked-choice voting faces a headwind. Could delegated RCV offer enough familiarity to most voters that an “delegated ranked-choice voting” initiative could garner a majority of votes? Is there a better name for it? Something less jargony?

At this point, delegated RCV is just a spitball with no empirical evidence about how voters or candidates would actually respond. Tell me: what pitfalls do you see? What am I missing? What opportunities can you imagine for road testing it in the real world to gather information about how it works in practice. Might high school and college student body elections give it a try? Professional organizations? Would someone build an online simulator so that membership groups could easily try it out?

Central to my inquiry, though, is this: Is this idea a better way forward to get proportional representation in North America? Or is it a dead end? I welcome your thoughts in the comments below.

Comments are closed.