Few public policy issues can match urban housing politics for its incendiary combination of passion and misconception. To wit: the confounding idea that relaxing regulations and fees to decrease the cost of homebuilding won’t make homes more affordable.

Why? Because, goes the refrain, developers charge as much as the “market will bear” anyway. Any savings from streamlined regulations or reduced fees just yield more profit for the developer, not lower prices or rents.

That reasoning may sound legitimate, but it’s bogus. It misses the forest for the trees—or, the city for the building. Across an entire metropolis, when homebuilding is cheaper, homebuilding speeds up. And in booming, housing-short cities such as Seattle, the more new homes built, the less prices rise—that is, the lower the price the market will bear.

Why does this misconception about costs matter? Because it excuses counter-productive housing policy.

Why does this misconception about costs matter? Because it excuses counterproductive housing policy. Why bother fixing ill-conceived regulations that boost the expense of homebuilding if you believe doing so won’t help affordability? If you believe it just puts more money in developers’ pockets?

What’s more, the confused logic also infects debate over adding costs: if the market sets prices with no regard for cost, it follows that policies that increase the expense of homebuilding can’t raise home prices. This rationale frees policymakers to ignore that imposing impact fees on new homes, for example, is likely to exacerbate their city’s affordable housing crisis.

It’s flawed thinking. It’s all too common. And it needs to stop if booming cities are to get housing prices under control. So let’s unpack it.

The real cost of red tape

Most people accept that if someone figures out a cheaper way to make a product, the price will drop. Producers make more, and the price the market will bear goes down.

A recent study conducted by the City of Portland, Oregon, estimated that on average, “government fees” add 13% of the total development cost of housing.

For housing, the rules that govern development often conflict with cheaper production. Drawn-out permitting processes and legal challenges add cost because time is money. Minimum apartment sizes effectively mandate more expensive apartments. Requirements that complicate building design—such as setting back top floor facades further from the street—raise the cost of construction. A recent study conducted by the City of Portland, Oregon, estimated that on average, “government fees” add 13 percent of the total development cost of housing.

For a real-world example, consider this story from Portland: in 2010 the city waived system development charges—typically ranging from $8,000 to $11,000—on accessory dwelling units (ADUs, otherwise known as mother-in-law apartments or backyard cottages). For most homeowners financing is the biggest hurdle to adding an ADU, and it’s not hard to imagine that the prospect of writing an extra $10,000 check just to get started would scare off many. Sure enough, after Portland removed the charge, ADU permit applications took off.

From pencil to project

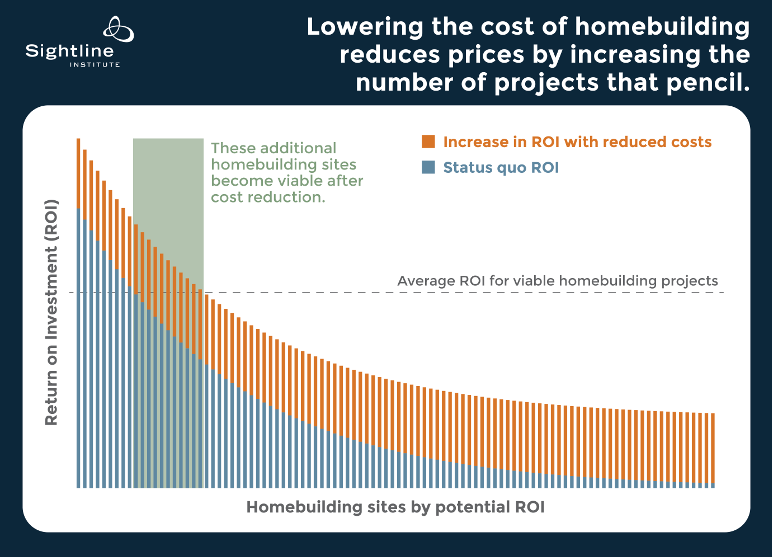

Developers build homes until the market becomes saturated and falling sale prices (or rents) no longer generate an adequate return on investment. However, if a city changes a rule or trims a fee and reduces costs, developers’ returns improve. Consequently, more homebuilding projects “pencil,” and more homebuilders get into the game. Less expensive homebuilding means more new homes get built and then sell for lower prices.

The diagram above illustrates the concept. Across a typical city, the potential return on investment (ROI) from homebuilding varies widely depending on site-specific conditions. Each blue bars represents one building site in an imaginary city, with the bar height indicating its potential status quo ROI. The orange bars show how a cost-cutting measure could increase ROI. (It’s an optical illusion that the orange bars are growing to the right—they are all the same length atop the blue bars). In practice there is no precise threshold ROI that makes all projects pencil, but for clarity the diagram depicts an average threshold ROI. Sites with ROI higher than the threshold pencil, and sites with ROI lower, don’t. As delineated by the shaded green area, decreasing the cost expands the number of sites where homes could likely be built.

Policymakers sometimes have reservations about altering regulations to cut costs, worrying that they are just handing windfalls to builders without helping affordability. In the larger picture, though, reducing the cost of homebuilding makes all housing throughout the city more affordable by shrinking the average price the market will bear.

Pause: this is not an argument to eliminate all housing regulations or fees. For example, most life-safety building codes are well justified. However, many other rules are not, especially given their tradeoff with affordability.

Trying to have it both ways

It may not be surprising that anti-housing activists resort to arguing that reduced costs don’t matter, but it is disappointing to hear similar thoughts from professional policymakers, who exhibit an oddly divided mind about it. On one hand, countless municipalities offer developer incentives intended to boost homebuilding. For example, the City of Seattle’s Housing Affordability and Livability Agenda includes numerous recommendations for cost cutting, ranging from design review improvements to building code updates for inexpensive wood construction.

On the other hand, urban planners and advocates across North America commonly contend that added costs don’t harm affordability, a prominent case in point being inclusionary zoning, which imposes costs on homebuilding by requiring private developers to provide below-market-rate homes.

In a recent interview with Vox, former Vancouver, BC, planning director Brent Toderian demonstrates the mindset in a discussion of mandates for family-sized units: “Economic analysis shows that two- and three-bedroom units can be less profitable than one-bedrooms or studios, but that’s not the same as saying that they aren’t viable.”

Here, Toderian glosses over a fundamental truth: “less profitable” prospective homebuilding projects are less likely to ever get built. Some fraction of projects may remain financially viable despite costly requirements, but another fraction will not. And the absence of this latter fraction from the city’s housing choices in the years ahead will increase competition throughout the housing market, raising prices. The figure above shows how this works.

Not to pick on Toderian—his views are commonplace among urban planners—but he recently provided another good example on Twitter in response to concerns that a new development fee would drive up prices: “Developers always claim that,” he wrote. “Still not true. Fees push down land value or profit from contingencies. Homes sell for what market will pay.”

User Suburbanist tweeted back, “But fees change market conditions. Buyers bid prices up when fees lower supply.”

To which Toderian responded, “Show me where fees lower supply.”

Unfortunately it’s impossible to do a controlled experiment on two otherwise identical real cities to prove that fees on homebuilding lower the supply of new homes. So the question to ask is: why wouldn’t they?

No land sale means no new housing. And no new housing means greater upward pressure on prices.

The standard retort is that added fees depress land values, so landowners, not homebuilders, take the financial hit. But as I have argued in detail previously, that claim doesn’t withstand scrutiny. It ignores the fact that most urban property already generates revenue, and owners always have the choice to keep collecting rents until offered a price high enough to make it worth selling. No land sale means no new housing. And no new housing means greater upward pressure on prices. There’s no wiggling out of it: affordability still suffers when fees depress land prices.

There is nothing magical about housing that insulates its market price from changes in its cost of production. Land values do complicate housing economics in some ways, but they do not break the universal economic supply chain that links cost of production, quantity of production, and price.

Furthermore, there is no magic number below which cost-inducing regulations and fees have zero impact on prices. The gain is proportional to the pain. Some policymakers may want to believe that a little added cost won’t do any harm. But that is a perilous line of thinking, because it gives the green light to adding more and more little costs here and there. They pile up in bureaucratic layers over time, ultimately causing death of homebuilding by 1,000 cuts.

Extending the bottom of the ladder

Affordable housing crises in expensive cities such as Seattle will never be completely solved by streamlining counterproductive regulations that add cost. Nor by trimming fees. Even with perfect rules, high land values and the raw cost of construction put new homes out of reach to people on the lower end of the income ladder.

But here’s the crux: the more costs can be cut, the further down on that ladder housing will reach. The lower the price of market-rate housing goes, the fewer households will need public subsidy to afford homes.

So, yes, red tape and fees do raise the price of housing—and cutting them lowers it.

Comments are closed.