Editor’s note: We added three “made-in-Canada” Proportional Representation methods below: rural-urban, local, and dual member. Because of the Trudeau administration’s promise to move off of first-past-the-post voting, and BC’s impending referendum on electoral reform, Canada has been a hot bed of thinking around how to customize the benefits of Proportional Representation to the specifics of North American elections.

The legislative branch is the branch of government meant to “be dependent on the people alone.” All voters should feel they have a representative to voice their concerns in the federal, state, or provincial legislature, as well as on the county council, city council, and school boards. Yet in North America, these bodies often reflect only the largest group of voters, leaving other groups without a voice.

What other options do we have for electing a legislative body more representative of their diverse constituencies? This glossary summarizes how different election methods work for electing multiple people to serve in a legislature, their strengths and weaknesses, and how they have played out in real life.

This document doesn’t describe all the possible election methods, nor does it detail all of the quirks of each method. Rather, it is meant as a quick reference guide to give readers a sense of each method. This Glossary and the accompanying Guide to Methods for Electing Legislative Bodies are specifically about electing legislative bodies of government—that is, where more than one person serves in the same body at the same time. For example, state legislatures, provincial parliaments, and city councils are all multi-member legislative bodies. (For a discussion of election methods for electing executive offices where only one person serves at a time, see our Glossary and Guide to Methods for Electing an Executive Officer.)

Legislative election methods generally fall into two families:

- With Majoritarian methods, used in the United States and Canada, all or most legislators represent majority views while minority groups do not have fair representation. Usually, two major parties representing the social or political majority dominate the legislature.

- With Proportional methods, used in most developed countries, legislators more fairly represent the diversity of voters. Usually, several parties representing a diversity of social and political views win seats in proportion to the votes they receive.

This document also describes two systems in each of the following two categories:

- With Semi-proportional methods, used in local elections across the United States, minority social or political groups have a chance to win seats.

- Potentially Proportional methods have not been used in any public elections, but might achieve proportional results.

The advantages and disadvantages of each category apply to all methods in that family, and each method has some unique advantages and disadvantages.

Overview of Majoritarian Methods

Also called “plurality,” “majority,” or “Westminster model” methods.

With “majoritarian” methods, voters in the major social or political group are able to elect all or most of the legislators. Voters with views in the minority have few or no seats. Minor parties may win some seats, but not proportionally to their numbers of voters, and two major parties usually dominate the legislature.

Many majoritarian methods use single-winner races, which includes both single-member districts and at-large posted seats where the legislator in each race must win either a plurality (more votes than any other candidate, but not necessarily a majority) or a majority (more than half) of the votes in that district. In each of these races, a candidate representing majority views is most likely to be the one winner, so someone representing minority views rarely wins a seat.

All majoritarian election methods share the following advantages and disadvantages, but each has its own specific advantages and disadvantages.

Advantages

- Ballots are simple.

- Voters have a clear choice between two “big tent” parties. Political choices are not fragmented into many minor parties.

- One big tent party is in control of the legislature and can enact cohesive policies. The opposing party can check the other party’s power and give voters a coherent alternative policy view.

- It may be hard for extreme candidates to win legislative seats (except when party primaries and “safe” districts let them in).

Disadvantages

- Minority groups, whether political, religious, racial, ethnic, or other, are excluded from fair representation.

- Few women are elected. Ninety percent of countries with no female representation use majoritarian methods. In countries with 10 percent or fewer women in the legislature, a majoritarian method is most common.

- Many voters feel they waste their votes, because they almost never have the experience of voting for a candidate who actually wins. This pattern can alienate and discourage voters and mobilize movements against the whole system.

- Majoritarian countries have lower voter turnout than proportional countries.

- Policies reverse regularly as power switches from one party to the other, making long-term economic planning difficult.

- Majoritarian countries perform poorly on several empirical measures of social well-being: they have higher wealth inequality, more gender inequality, worse protection of the environment, more obesity, and less clean energy than proportional governments. They also put more people in prison, are more likely to use the death penalty, are more likely to engage in domestic surveillance of their own citizens, have higher military expenditures, have higher national debt, and are more likely to engage in international conflicts than proportional representation countries.

- Candidates in majoritarian methods are more likely to promise quick fixes than to seek long-term solutions to complex problems.

- At first glance, majoritarian systems seem to promote “majority rule,” but in reality a majority of legislators, each representing a majority of voters in their districts, can pass legislation that does not represent the majority of voters in the country (because the minority of voters in their districts, and arguably all of the voters in the districts of the legislators who did not vote for it, had no say).

Majoritarian: Single-Winner Races

Legislators can be elected through single-winner races—a race where only one candidate will win a seat, as opposed to multi-winner races where candidates run in a pool for several available seats—using any of the election methods described in the Glossary of Methods for Electing Executive Officers. Single-winner legislative races can occur in single-member districts (or “ridings,” in Canada), numbered seats within a district (like Washington’s state representatives), or at-large numbered seats (like Portland’s city council).

Electing legislators with single-winner races, even with ranked-choice or score voting, leads to majoritarian results, where the social or political majority wins almost all the seats and, usually, two major parties divide most of the power. Parliamentary systems like Canada’s yield slightly more diversity of party representation than Presidential systems like the United States’, and Duverger’s Hypothesis predicts that Top-Two Runoff makes it easier for third parties to win sometimes (though the evidence indicates this is not necessarily true), but single-winner elections for legislative seats always yield less-than-proportional results.

Whether elected by Plurality, Top-Two Runoff, or Instant Runoff Voting, electing legislators in single-winner races has the advantages and disadvantages below.

Advantages

- In a single-member district, voters in a geographic district have a direct link to their representative. They know who their local representative is and can call her to voice concerns, or refuse to vote for her again if she doesn’t represent them well. (Some proponents of single-winner districts say it is easier to for voters to “throw the bums out,” but in reality, in the United States, incumbents almost always win re-election.)

- The legislature represents the geographic diversity of the city, state, province, or nation.

- Voters can vote for an individual candidate (and if the jurisdiction allows full fusion voting, voters can also indicate a preference for a party).

Disadvantages

- Single-member districts are vulnerable to gerrymandering. With slight changes to the district lines, a district can shift from being safe for one major party to being safe for the other major party, allowing the line-drawers, not the voters, to determine how many seats a party can win.

- Even without intentional gerrymandering, one party can win control of the legislative branch even though another party won more votes. For example, in 2012, Republican candidates won just 47.6 percent of the vote (compared to Democrat’s 48.8 percent), yet Republicans then controlled the US House of Representatives.

- Voters in the minority cannot hold their representative accountable. A Democratic representative won’t feel very accountable to a Republican voter in her district because she knows he didn’t vote for her, and it doesn’t matter if he doesn’t vote for her again.

- The legislature does not represent the ideological diversity of the city, state, province, or nation.

- Single-member districts may give incumbents more advantage: incumbents are more likely to run again and less likely to face an opponent in single-member districts.

- Single-member districts may force candidates to raise more money to be successful.

- In nonpartisan races, voters cannot indicate a preference for any party, and in partisan races without full fusion voting, voters may not be able to indicate their preference for a minor party.

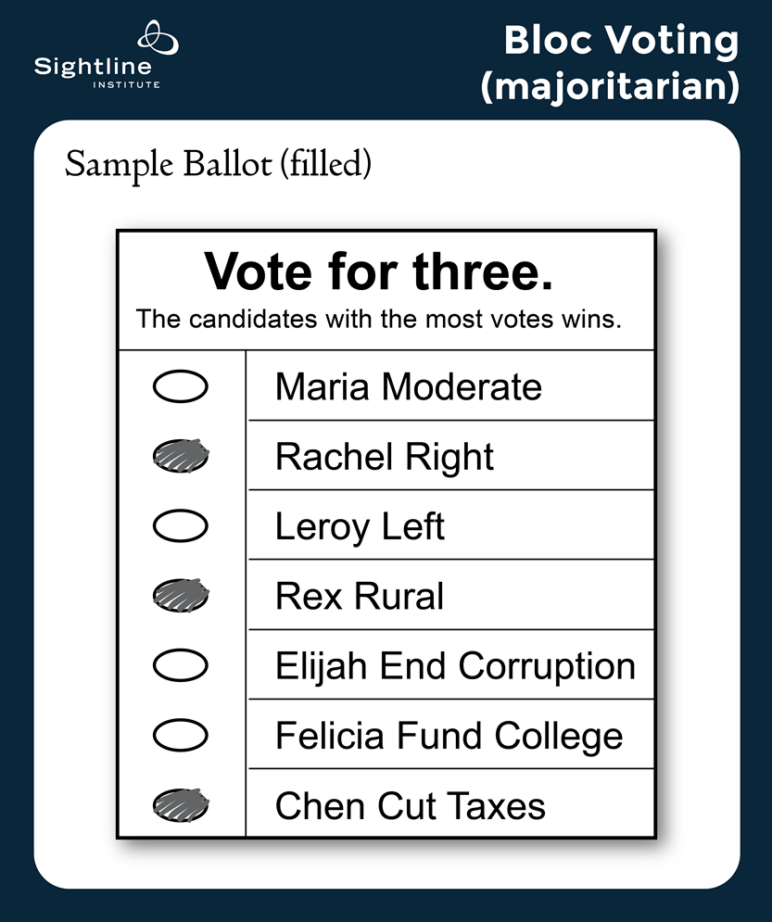

Majoritarian: Bloc Voting

Also called “plurality at-large voting.”

In bloc voting, candidates run in a common pool for multiple available seats. The pool could be for the entire jurisdiction (city-wide or country-wide) or for a multi-member district. Voters can cast as many votes as there are seats available, and the top vote-getters win the seats.

If voters with a majority view cast their votes for a slate of candidates with majority views, that slate will sweep the entire election, even if voters with minority views cast all their votes for candidates with minority views.

However, Bloc Voting has been proven to elect more women than single-winner races. Parties may be more inclined to include a woman in a list of candidates running for a pool of seats than they would be to run a woman in a single-winner races. And voters are more inclined to include a vote for a woman candidate when they can, for example, “Vote for Five,” rather than when they have only one vote.

For example, New Hampshire uses a mix of single-member and multi-winner districts to elect the state legislature. Generally, one party dominates each district and wins all of the seats. However, in 2012, Republicans lost six seats in districts they otherwise dominated. All six seats went to Democratic women candidates. The Republican party hadn’t included enough women in its list of candidates, and it appears that voters were willing to cross party lines to elect a woman when given a chance to choose more than one.

More than one hundred cities in Oregon use this method for their respective city councils. For example, Lake Oswego voters can “Vote for Three” candidates from a pool, and the top three vote-getters win seats on the city council. Vancouver, BC, and many other Canadian cities use Bloc Voting to elect city councils.

Advantages

- Bloc Voting elects more women than single-member districts or at-large numbered seats.

- Compared to single-member districts, multi-member districts may make it likelier that new candidates will challenge incumbents.

- Compared to single-member districts, multi-member districts may allow candidates to run less expensive, successful campaigns, in part because they may run in a slate and share costs with other candidates.

- Bloc voting strengthens parties that demonstrate coherence and organizational ability because they are able to run a coherent slate of candidates and organize voters to vote for the slate.

Disadvantages

- Bloc Voting may result in even more disproportionate results than single-winner districts because it may allow the prevailing social majority (for example, the majority racial or religious group in the district) or the dominant major party to win all or most of the seats on the ballot, leaving minority voices with little or no representation. For example, New Hampshire uses Bloc Voting to elect members of its state house of representatives from districts with between two and twelve representatives each. In 2016, in 77 percent of those districts, one party won all the seats. Even in districts with 10, 11, and 12 representatives where 40 percent of the voters wanted representatives from the other party and, proportionately, should have won four or five of the seats, those voters got zero representation.

Overview of Proportional Methods

Also called “fair representation” or “consensual” methods.

With proportional methods, the legislature reflects the social and political diversity of the voters. When societies have ethnic, religious, or other cultural or political divisions, each group has the chance to elect representatives they support to the legislature. If 40 percent of voters prefer one political party, that party wins 40 percent of the seats. Or if 20 percent of the voters want representatives of color, people of color win 20 percent of the seats. Although some countries or political parties also make use of quotas or reserved seats for women or for ethnic minorities, the methods below can achieve proportional representation of ideological diversity and often elect more women and people of color though individual votes, not quotas.

Voting experts sometimes call these “consensual” systems because legislators must work together to craft broadly acceptable solutions. Most advanced democracies, and all countries electing members of the European Parliament, use some form of proportional representation.

Advantages

- All voters, no matter their political party, religion, race, ethnicity, or gender, can achieve fair representation. The legislature represents the diversity of the city, state, province, or nation.

- Almost all voters get to vote for at least one winning candidate—very few votes are “wasted.”

- Proportional methods mitigate the power of gerrymandering, because parties can only win more seats by winning more votes, not by drawing district boundaries.

- They reduce “regional fiefdoms” where one party controls all the seats in a region.

- The ruling coalition elected with a proportional method often has greater total support (55 or 60 percent of voters voted for members of the coalition) than the ruling party elected with a majoritarian method. For example, members of the ruling coalition in Germany received 67 percent of the vote, while members of the ruling Republican Party in the US House of Representatives received only 49 percent of the vote.

- Proportional methods lead to greater continuity and stability of policy. Policy often takes longer to pass, but is more stable over time because many different groups helped shape it, so it is not thrown out as soon as a different party wins more seats.

- More people participate in elections and vote.

- Decisions are more transparent and inclusive because they are carried out publicly between multiple parties rather than behind closed doors within a party.

Disadvantages

- If thresholds for participation are too low, proportional methods may lead to extreme multi-party fragmentation. (Some theorists suggest there is a tradeoff between policy stability and government stability: in other words, countries with proportional parliamentary systems will shift coalitions frequently but maintain steady policies, whereas countries with majoritarian presidential systems will have stable parties but many policy flip-flops.)

- Candidates with extreme views can win seats in the legislature.

- The Speaker of the House or President of the Senate will be a member of a party that likely won less than half the votes. (However, she will be the head of a coalition that likely won much more than half the votes.)

- If districts are too large, legislators may lose their geographic link to voters. (However, if geography is important to voters, in most proportional systems they can vote for a local candidate or party and elect that person. In List systems, the parties usually take geographical diversity into account when creating their lists.)

- Voters may not be able to throw a centrist party out of the ruling coalition, so long as that party is able to come to agreement with the other parties.

- Many proportional ballots are more complex than “vote for one” ballots.

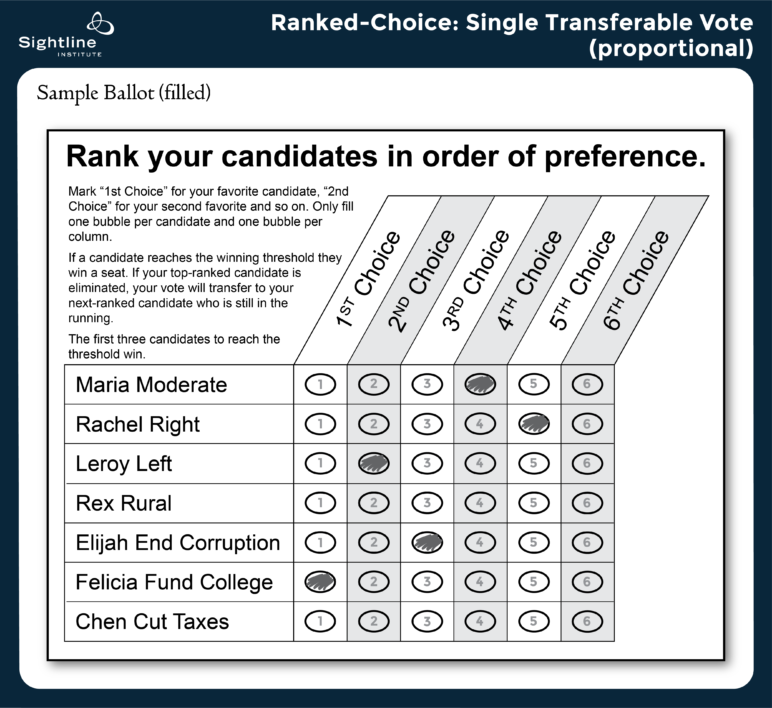

Proportional: Multi-Winner Ranked-Choice Voting, a.k.a. Single-Transferable Vote

Single Transferable Vote (STV) is a multi-winner form of Ranked-Choice Voting (RCV). Multiple candidates run in a common pool in a multi-member district, so several of them will win office. Ideally, districts each elect five members, though three and seven also work well. Voters rank their candidates in order of preference, and if a candidate reaches the winning threshold, she wins a seat. All votes for candidates who received too few first-place votes, plus fractions of all votes above the threshold for a candidates who already won a seat, are transferred to voters’ next-choice candidates who are still in the running. Counting and transferring continues until enough candidates have reached the winning threshold. (Two videos explain, using jungle animals and post-it notes.)

As in the single-winner form of Ranked-Choice Voting, known as Instant Runoff Voting, voters get just one vote per round, and a candidate must have sufficient votes in a given round to make it to the next round.

Let’s take a hypothetical case for a Northwest legislative body. If Oregon were to elect its 60-member house of representatives using multi-winner Ranked-Choice Voting, it could, as one option, divide the state into 12 districts (each a bit more than twice as big as current state senate districts) and elect five members from each district. Voters would elect their five representatives by ranking candidates on a ballot like the one above.

Single Transferable Voting is used in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Ireland, Australia, local elections in Scotland and New Zealand, and for Academy Awards nominees. More than a dozen US cities used multi-winner ranked-choice voting in the early 20th century. STV cities elected diverse councils, including people of color and minor-party representatives, leading to successful repeal efforts. In 2004, a British Columbia citizens assembly (two people randomly selected from each electoral district) studied election methods and recommended STV, a.k.a. multi-winner Ranked-Choice Voting. A 2005 referendum to use STV in BC elections won 58 percent of the popular vote, but needed 60 percent to go into effect.

Advantages

- Voters can vote for individual candidates, not just for a party.

- As long as districts are not too large, or voters vote for local candidates, legislators retain a geographical link and accountability to voters.

- Voters can hold representatives accountable. Each voter will almost always have at least one representative for whom they voted, and they can call that representative up or refuse to vote for them again.

- Voters don’t need to be organized to achieve fair representation—they can just vote their preferences.

- Voters can vote for the candidates they like best to represent their region, their ideological views, and their life experiences, without worrying that ranking a less preferred candidate could cause their favorite candidate to lose and with few concerns about choosing the “lesser of two evils.”

- Because it is not party-based, it can be used in local or non-partisan races.

Disadvantages

- The ballot is more complicated than “vote for one,” and the counting is complicated.

- If the number of representatives for a multi-member district is too small, results will not be highly proportional. For example, in a two-member district, candidates with support from less than one-third of the voters won’t be able to win a seat.

- A candidate without enough top rankings will get eliminated, even though she had more subsequent rankings than other candidates and so would have won a seat had she remained in the contest. (Over the years, electoral tinkerers have attempted to “fix” this, for example by adding eliminated candidates back in in future rounds, but such fixes could suppress voters from ranking additional candidates, for fear that those additional rankings will cause their more-preferred candidates to lose. If candidates don’t rank additional candidates, the method might not achieve proportional results.) (However, this can also be considered an advantage, because it is part of what allows this method to achieve proportional, not majoritarian, representation.)

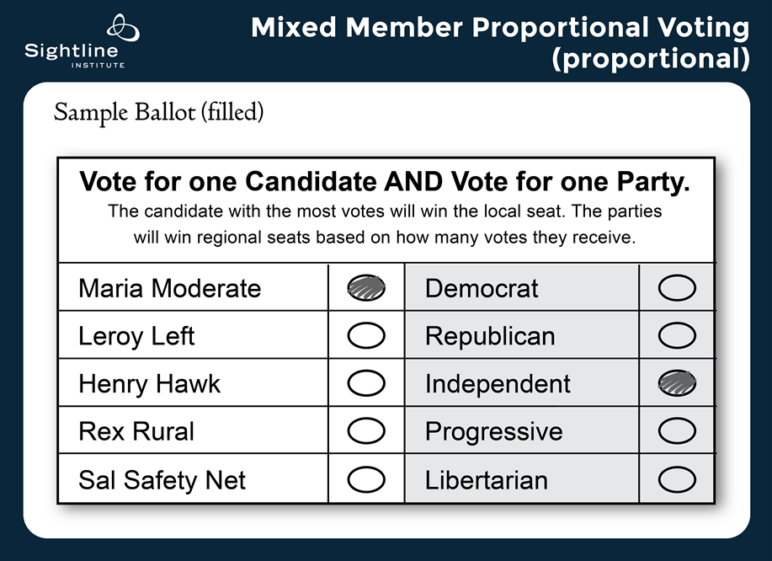

Proportional: Mixed Member Proportional

Mixed Member Proportional (MMP), also called the “additional member system,” is a hybrid, electing some representatives in single-member districts and some from multi-member regional or nationwide districts. Voters get two votes: one for your local district representative and one for a regional or national party. Regional or national seats are assigned to ensure each party’s share of the total legislative seats is proportional to its share of the vote, and the party chooses which candidates fill its seats. (Videos explain here and here.)

As an example, if Washington were to elect its 98-member state house of representatives using Mixed Member Proportional, it could, for example, establish 48 local districts, each about the same size as the state’s current 49 legislative districts, and with one representative each whom voters would elect in the same way they do now. The other 50 members could come from 10 regional districts, each the same size as a federal congressional district, and with 5 representatives from party lists. Voters would elect these members by voting for a party, as in the ballot above. Voters would have one local representative and also five regional representatives in the house.

Germany, New Zealand, Scotland, Wales, and several other countries use Mixed Member Proportional voting to elect their national legislatures. Most of the gains for women and people of color come from the multi-member districts, not the single-member districts. Prince Edward Island, a province on the east coast of Canada, voted in 2016 to adopt Mixed Member Proportional Voting to elect its provincial legislature.

Advantages

- Under Mixed Member Proportional Voting, local representatives retain a geographic link to their voters.

- Voting for one candidate in a single-winner district would be familiar to American and Canadian voters.

- Ballots are relatively simple.

- Because voters retain a local representative, the regional districts could be larger, allowing for more proportional results than STV.

Disadvantages

- With MMP, the local districts still use single-member districts and so are vulnerable to gerrymandering.

- Because the regional list is party-based, it can’t be used in local nonpartisan races.

- In rare cases, it could lead to a party strategically telling voters to vote for a different candidate in order to keep its national seat(s).

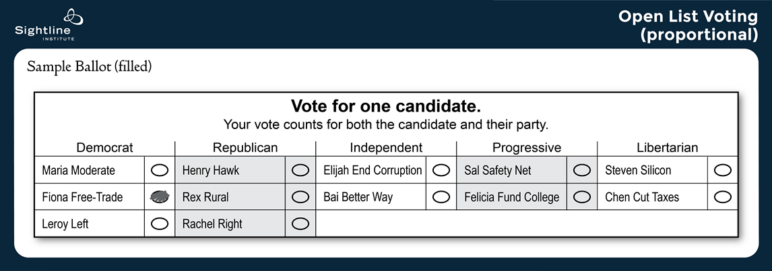

Proportional: List Voting

List Voting, which comes in both Open and Closed forms, is the most common form of proportional representation. Candidates run in large multi-member districts or sometimes statewide, provincewide, or nationwide, depending on the jurisdiction of the legislature. The ballot lists candidates by party.

In Open List Voting, voters can vote for their favorite candidate within a party list, and their vote will count for both the candidate and the party. The party wins seats in proportion to the number of voters who chose any candidate on their list, and the candidates who won the most votes fill the seats. Open List Voting gives the party the power to choose who appears on its list, but gives voters the power to express which candidate they like the best.

For example, if all Republican Party candidates collectively won 60 percent of the vote in a three-member district, Republicans would win two of the three seats. If Rex Rural and Rachel Right were the top two Republican vote-getters, they would get the seats. Voters who chose Henry Hawk would not get their favorite candidate, but they would contribute to electing two Republicans in their district.

If Oregon were to elect its 60-member house of representatives using Open List Voting, it could, for example, divide the state into 12 districts, each a bit more than twice as big as current state senate districts, and with five members from each one. Voters would vote for their one favorite candidate, listed by party on a ballot like the one above, and the top five would represent that district.

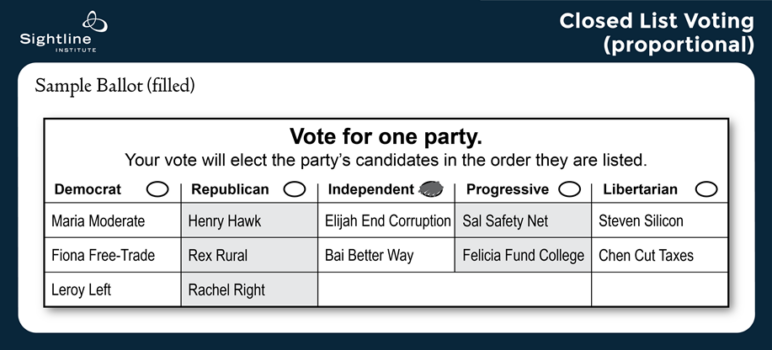

In Closed List Voting, voters cast one vote for a party, and the party assigns candidates to seats in the order listed on the ballot or on the party’s list. Closed List Voting gives parties the power to order the list, and voters must accept that order.

For example, if one-third of the voters in a three-member district chose the Independent Party, the party would win one of the three seats, and the seat would go to Elijah End Corruption, the candidate listed first on the ballot.

Advantages

- List Voting elects more members of minority racial or ethnic groups.

- It also elects more women. Fifteen of the top 20 nations in the world in terms of female representation use List Voting. Legislatures using List Voting elected an average of 9.1 percent more women than majoritarian legislatures. Every country in Western Europe where women make up more than 20 percent of the legislature use proportional representation, mostly List Voting.

- Because this method usually elects dozens of members per district, List Voting achieves highly proportional results; people making up even just a few percent of the population can win representation.

Disadvantages

- Because voters don’t have a say, with Closed List methods, in which individual candidates are elected, the link between legislators and constituents can be tenuous.

- The parties have a lot of power, especially with Closed List methods. Americans may not be comfortable with strong party power.

- Especially in parliamentary systems where several parties must form a coalition government, small parties may hold larger parties to ransom in coalition negotiations.

- Because it is party-based, it cannot be used in local nonpartisan elections.

Proportional: Rural-Urban PR

Rural-Urban Proportional Representation (R-U PR), a “made-in-Canada” solution, uses Single Transferable Vote in urban and suburban areas and Mixed member Proportional in rural areas. Rural districts can retain their local representation with single rural districts, but the overall legislature will be fairly proportional. Only about 10-15 percent of the seats need to be used for top-up purposes in R-U PR, as compared with 35 to 50 percent of seats with MMP.

Rural-Urban Proportional Representation would use two types of ballots:

- Local single-winner districts in sparsely populated rural areas. The ballot could be ranked or “vote for one” plurality.

- Suburban and urban voters would see a multi-winner ranked ballot electing two to six representatives per district.

- Rural voters might see a Mixed Member Proportional ballot where they could choose their favorite local representation and their favorite party. Or, they could see a traditional First Past the Post ballot and regional top-up winners would be the strongest remaining candidates from the local elections.

Here’s a hypothetical example of how it might work in British Columbia’s provincial elections. BC has 87 Members of the Legislative Assembly (MLAs), each elected from a single-winner district. Rural-Urban PR might:

- Elect 75 local MLAs:

- 8 from rural districts—1 from each of eight single-winner rural districts

- 12 from suburban districts—three each from four multi-winner districts

- 55 from more urban districts—five each from eleven multi-winner districts

- Elect 12 top-up regional MLAs—the strongest additional candidate from each of twelve regional districts encompassing several smaller local districts

Advantages

- Highly proportional.

- Local representatives retain a close geographic link to their voters.

- Voting for one candidate in a rural single-winner district would be familiar to American and Canadian voters.

- Few top-up seats are needed, and they can come from natural regions of moderate size, not just the province at-large.

- Nearly all voters will have voted for an elected representative by name.

Disadvantages

- Could be a bit complicated to explain.

Proportional: Local PR

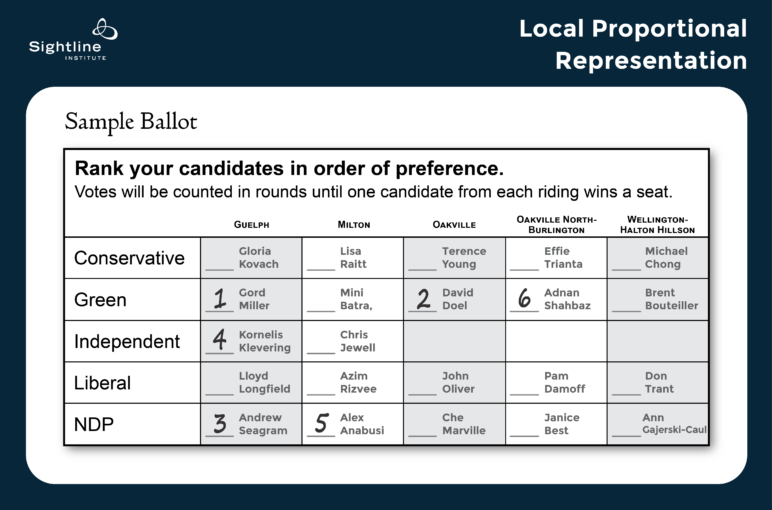

Local Proportional Representation keeps existing ridings or districts, but allows voters to vote for candidates across a larger region. It combines four to seven existing local ridings into a region and lists candidates based on the local riding they are from and their political party. All voters in the region can rank as many candidates as they wish, regardless of riding or party. One candidate from each riding wins a seat.

Votes are counted in rounds, with first-choice votes counted first. If no candidate reaches the quota with first-choice votes, the candidates with the fewest votes is eliminated and his or her votes are redistributed to the next-ranked candidates still in the running. When a candidate reaches the quota, she or he wins a seat and all other candidates from that riding are eliminated. In the next round, all candidates are in the running again, except for those in the riding that was already decided. Excess ballots for the candidate elected in that riding are fractionally distributed, as in STV, while ballots for eliminated candidates (all other candidates from the riding where one candidate won) are distributed to the next-ranked candidate. Counting continues until one candidate in each riding wins.

Local PR evolved from a proposal submitted to the federal Electoral Reform committee by Byron Weber Becker and Antony Hodgson (Fair Voting BC) in response to an invitation to produce a voting system design similar in concept to the Rural-Urban PR model (see above) that could be implemented without changing existing riding boundaries. The advocacy group, Democracy Guelph, extended and refined this idea and lobbied for it under the name Local PR. Below is a sample ballot with ridings in Guelph, Ontario.

Advantages

- Retains the same number of ridings and the same number of representatives currently in place.

- Guarantees geographic diversity of elected representatives.

- Local representatives retain a close geographic link to their voters.

- Proportional results.

- Nearly all of voters will have voted for an elected representative by name.

- Few wasted votes.

Disadvantages

- Matrix-style ballot will initially be unfamiliar to voters.

- Like the current system of single-winner ridings, Local PR could result in uneven quality of candidates if some ridings have a strong field and others have a weaker field of candidates.

- In some ridings, the candidate who wins the seat may not have won the most first-choice votes from voters in the riding.

Proportional: Dual Member PR

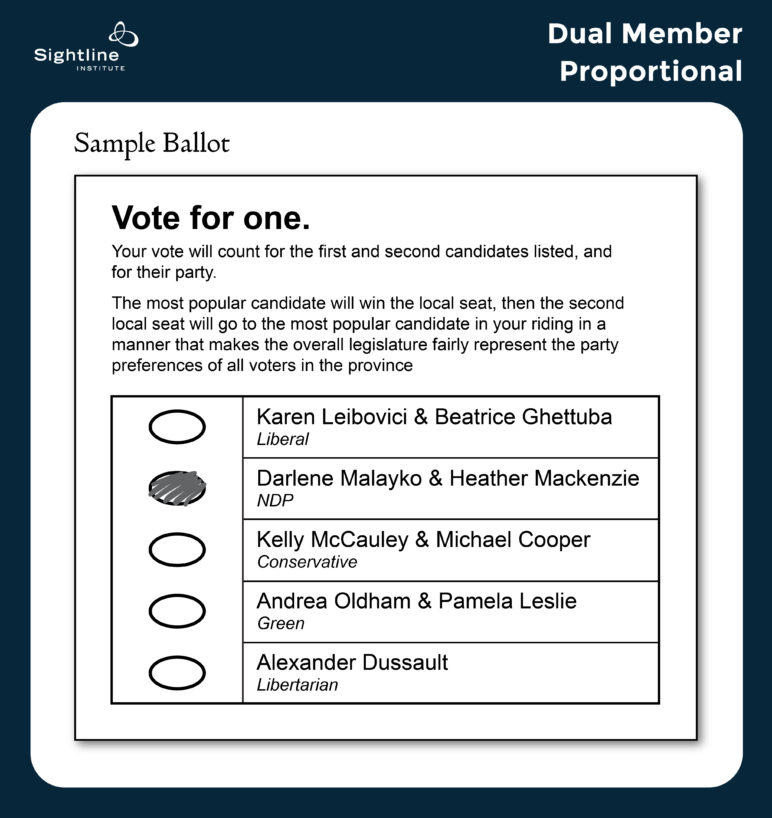

Dual Member PR (DMP), also known as Dual-member Mixed Proportional, is a made-in-Canada variant of MMP. DMP elects half the legislature from local districts and, like MMP, elects the rest to achieve party proportionately based on each party’s share of the overall regional vote. But where New Zealand-style MMP uses two separate ballot items (one for your favorite local representative, and one for your favorite party), DMP uses one simple, familiar, “vote for one” ballot, but with up to two candidates and their party on each ballot line.

The total number of representatives stays the same, but the number of districts is halved, so each riding (or district) has twice the number of voters as now and elects two representatives. In Washington, where each state legislative district already elects two representatives each, the number of districts could stay the same with DMP.

Voters would see a ballot like the one below, where each party gets to list up to two candidates per riding. The party picks which candidate is listed first and which second. Voters fill one bubble that counts for both candidates and their party. Alternatively, each candidate could have their own line, so voters could choose the candidate they prefer. In each riding, the candidate with the most votes wins the local seat. Then election officials would determine what share of the overall votes each party received, how many seats that party already won in the local races, and how many more seats it needs to achieve proportionality. It then fills those seats with the candidates from the appropriate parties who received the most votes in a riding. The first local winners are selected by plurality, just like now. Each riding has two representatives, and the legislature overall represents the party preferences of the voters.

The group DMP for Canada has used actual votes from provincial and federal elections in Canada to simulate how the election would have turned out with DMP.

Advantages

- Simple, familiar ballot.

- Proportional results (based on party affiliations).

Disadvantages

- In the variant pictured above, voters have only one mark on the ballot, meaning they can’t indicate support for the second party candidate over the one the party listed first, nor for a party other than the one their favorite candidate is a member of, nor for additional candidates beyond their favorite.

- About 65 percent of voters would have an MLA they specifically voted for. This is still much better than the 50 percent with single-winner districts and first-past-the-post voting, but not as good as the 90 percent or more with Rural Urban, Local PR, STV, and Open Party Lists.

Overview of Semi-Proportional Methods

The two methods below can achieve proportional results but are not guaranteed to do so. If voters in a political, racial, or social minority all vote in a cohesive bloc for their preferred candidate and no one else, they can attain representation. However, if voters in a minority split between two similar candidates then their candidate could lose. Overall, these methods would likely yield more diverse legislatures than majoritarian methods but not quite as diverse as proportional methods.

Many voting experts classify Limited Voting as a majoritarian method. The national reform organization FairVote categorizes STV, MMP, Limited, and Cumulative methods under the umbrella moniker “Fair Representation Voting Methods.”

Advantages

- Semi-proportional methods can achieve more representative results than purely majoritarian methods.

Disadvantages

- Semi-proportional methods can only achieve representative results if voters in a minority are organized and vote cohesively.

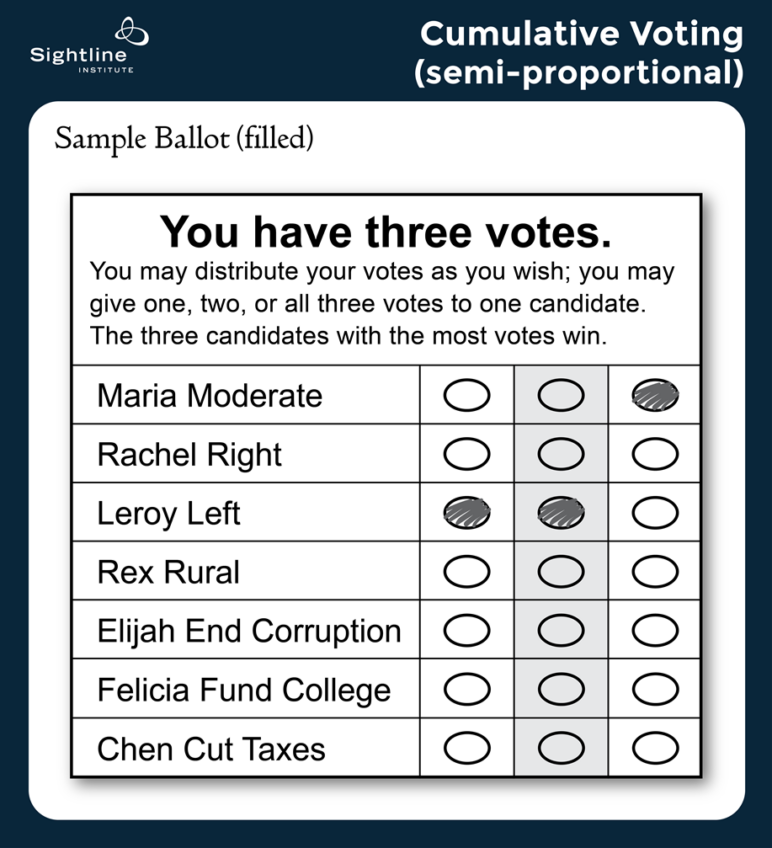

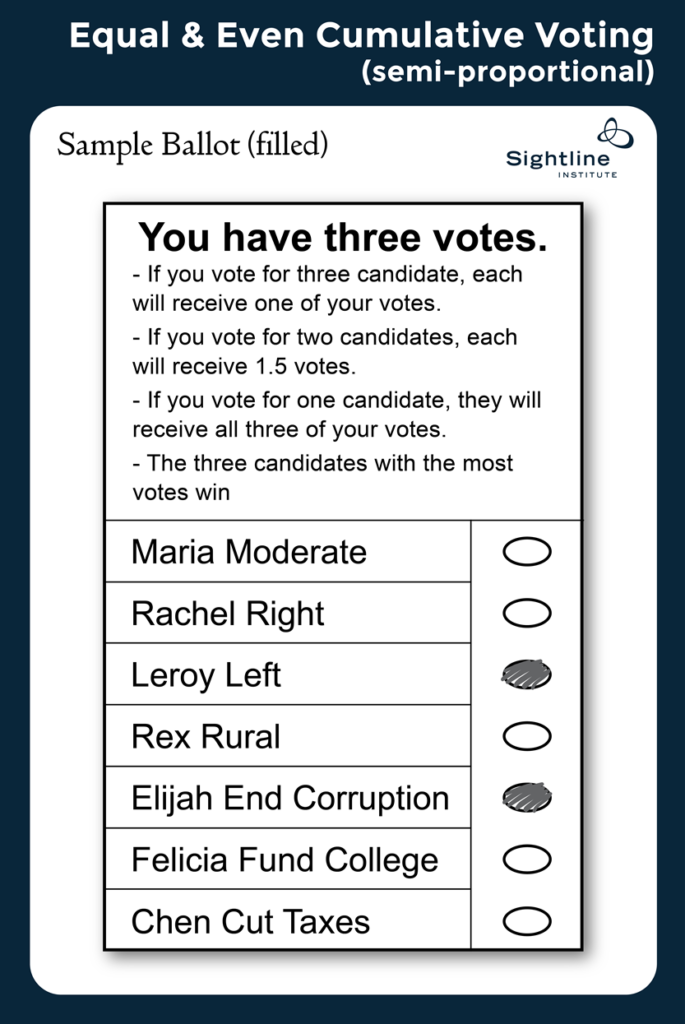

Semi-proportional: Cumulative Voting

Voters can cast as many votes as there are seats available, and they can choose to allocate more than one vote per candidate. For example, in a three-member district, voters can give all three votes to their favorite candidate, or two votes to their favorite and one vote to their second favorite, or one vote each to three different candidates. In “Equal & Even Cumulative Voting,” if voters fill in just one bubble, all three of their votes go to that candidate. If they fill in two bubbles, each of the two candidates receives 1.5 of their three votes.

Civil rights attorney Lani Guinier championed Cumulative Voting as a more equitable way to achieve diverse racial representation than trying to draw majority-minority single-member districts. US federal courts sometimes order jurisdictions in violation of section 2 the Voting Rights Act to switch from “vote for one” majoritarian voting to multi-member districts with Cumulative or Limited Voting (Limited Voting is described below) because racial minorities who could not win representation under “vote for one” single-member districts or “vote for one” at-large numbered seats can win representation in multi-member districts with Cumulative or Limited Voting.

More than 100 local jurisdictions in the United States use Cumulative or Limited Voting, and several dozen of these use Cumulative Voting specifically. Corporate stockholders, homeowners’ associations, and boards in some US localities use it to help elect more members from minority groups.

Advantages

- Ballots are easy to count under Cumulative Voting.

- This system can achieve representation for minority groups.

- It can be used in local, nonpartisan races.

- It allows voters to vote for more than one candidate.

Disadvantages

- Voters must be organized to achieve fair representation under Cumulative Voting. If voters in the minority split their vote, their favorite candidates will not win a seat.

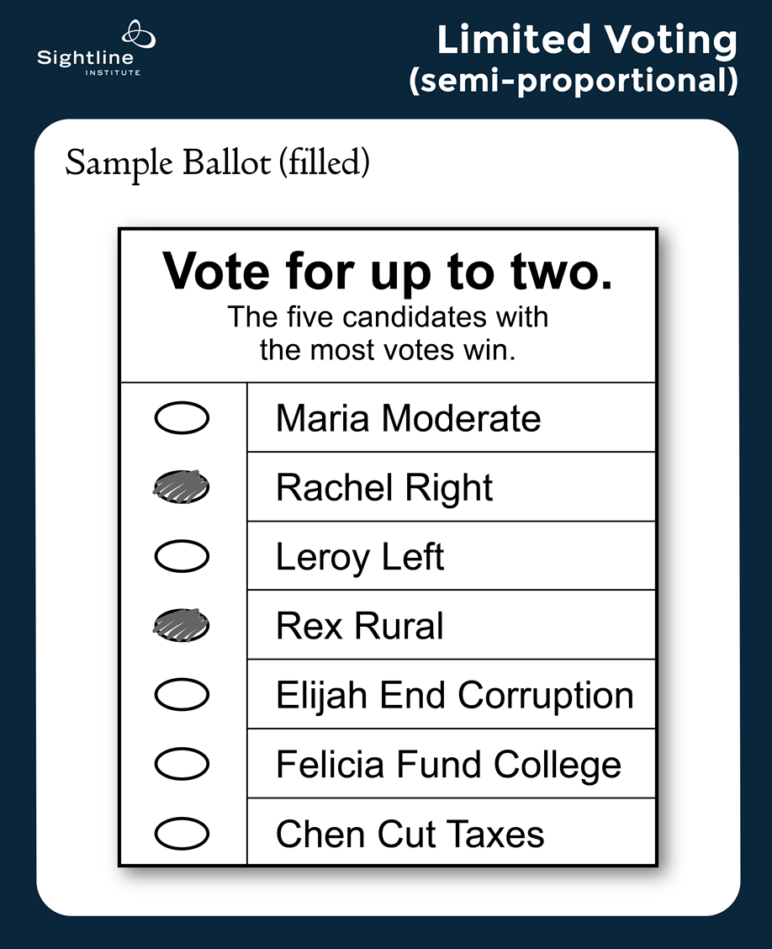

Semi-proportional: Limited Voting

In Limited Voting, voters may cast their votes for a given number of candidates that is smaller than the number of seats available. For example, in a five-member district, voters might be permitted to cast two votes, enabling minority voters making up about two-fifths of the population to elect two out of five seats. Or in a three-member district, voters might have just one vote each.

Some experts classify Limited Voting as a majoritarian method. Gibraltar and Spain’s upper houses use it, as do more than 100 dozen American cities and school boards, particularly in Alabama, Pennsylvania, and Connecticut.

If voters using a Limited Voting method are permitted to cast only one vote, it is called Single Non-Transferable Vote. Afghanistan, Pitcairn Islands, Vanuatu, and Indonesia use Single Non-Transferable Vote.

Advantages

- Ballots are relatively easy to understand and to count under Limited Voting.

- With proper coordination, Limited Voting can achieve representation for minority groups.

- It can be used in local, nonpartisan races.

- It can encourage parties to organize and reach out to voters.

Disadvantages

- Limited Voting can lead to disproportional results where one group receives a majority of the seats with just a plurality (rather than a majority) of the votes.

- Parties must be strategic in considering how many candidates to run, and voters must strategically spread their votes between candidates to achieve fair results. If parties and voters are not sufficiently strategic, they could waste a lot of votes—many voters cast their votes for candidates who never win or who would have won by a lot anyway so they lost the opportunity to elect someone else they liked. The sense that the strategy, not the voters’ preferences, determine the winners could harm voter morale.

Overview of Potentially Proportional Methods

The two methods below might achieve proportional representation, though they have not been used in any public elections, so it is hard to be sure. Some thought experiments suggest they might operate more like Cumulative Voting: if members of a minority group all give a maximum score to their favorite candidate and no scores to any others, then they can achieve fair representation. But if they give a score to a majority-view candidate they support, their minority-view candidate might not win a seat. Overall, these methods would yield more diverse legislatures than majoritarian methods, but maybe not as diverse as proportional methods.

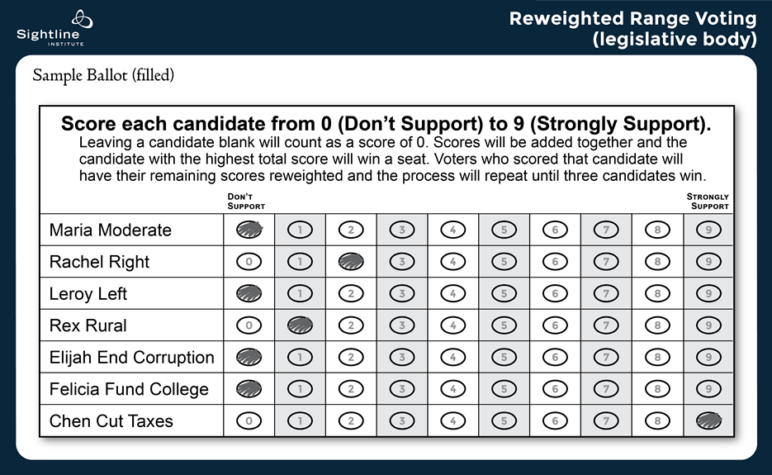

Potentially proportional: Reweighted Range Voting

In this multi-winner form of Score Voting, voters give each candidate a score, for example, from zero (or unscored) to 9. The candidate with the highest total score wins a seat. All the voters who scored that candidate have their remaining ballot weight reduced proportionally to their score for the winner. Reweighting makes it more likely to achieve proportional results. Reweighted ballots are counted, and the candidate with the highest score wins a seat. Adding and reweighting continues until all seats are filled. (A video explains, here.)

Just as in the single-winner form of Score Voting, Reweighted Range Voting incentivizes voters to only use the extreme ends of the available score range—that is, to give the maximum score to all candidates aligned with a voter’s views and give all other candidates a minimum or no score. So long as voters like all the aligned candidates, there is no penalty to giving them all a maximum score. If a party or group or faction has five candidates running and a good chance to elect three winners, aligned voters can safely give all five candidates a maximum score, and likely three of them will win. But differentiating between candidates could cause your group to get short-changed on fair representation. If, for example on a scale of 0 through 9, you give the five candidates a 9, 8, 7, 6, and 5, but voters with an opposing view give all their candidates maximum scores, your group might only elect two winners.

Another example: a minority group—say, the Green Party—has enough voters to elect one winner in a five-member district. If voters give a maximum score to the Green Party candidate(s) and zero to all others, they will elect one legislator. But Green voters aren’t sure if the Green candidate can win a seat and they still want to have a say in the election, or even if the Green can win they want to have a say in electing more than one of the representatives from the district, they will be tempted to also give middling scores to one or more of the major-party candidates they find acceptable. Meanwhile, the Democratic and Republican voters give maximum scores to multiple candidates from their parties, confident that they will elect several representatives with whom they are well-aligned, they may give no or a very low score to the Green Party candidate with whom they are less-aligned. The net result would be that the district sends five major-party legislators to the capital, even though one-fifth of voters wanted the Green Party candidate—a majoritarian, not proportional, result. With Reweighted Range Voting, It is not enough for voters in the minority to have the numbers to elect one-quarter of the legislature and for them to all turn out to vote and give their favorite a maximum score; they may also need to withhold scores from other candidates or else risk losing their representation.

This method has never been used in a governmental election, but the Berkeley City Council uses it to prioritize their list of legislative agenda items, and it is used to select the five OSCAR nominees for “Best Visual Effects.”

Advantages

- Reweighted Range Voting could be used in nonpartisan races.

- It might achieve more proportional representation than majoritarian methods.

- It ensures that voters’ scores for all candidates are counted and that a candidate with weak but broad support (lots of medium or low scores) is not prematurely eliminated.

Disadvantages

- The ballot and counting are complicated in Reweighted Range Voting.

- It has never been used in a governmental election.

- Voters in a minority group might not be able to elect their share of winners unless they withhold support from other candidates.

- In some circumstances, voters have to choose between getting the maximum amount of representation for their group of like-minded voters, or being able to choose which of several similar candidates would best represent them.

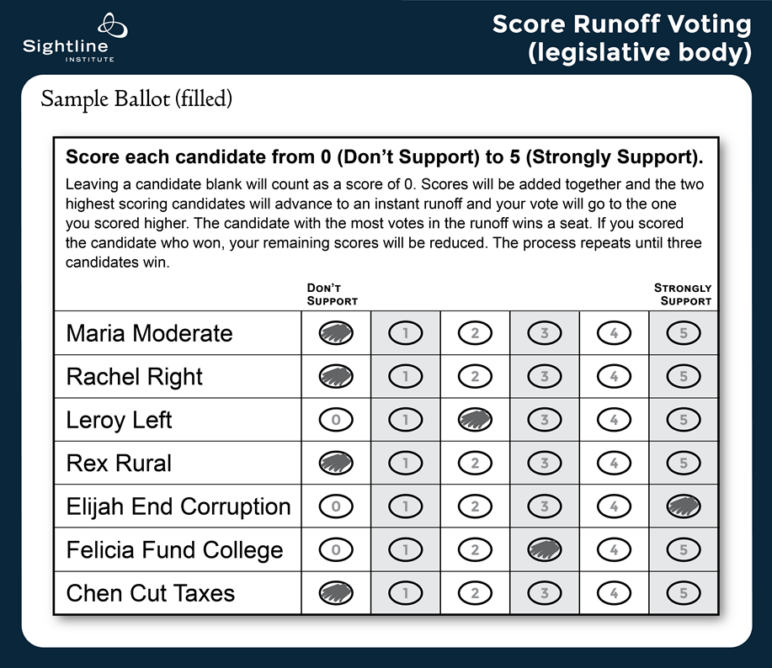

Potentially proportional: Multi-Winner Score Runoff Voting

Proportional Score Runoff Voting (SRV-PR) is the newly invented multi-winner form of Score Runoff Voting. It is a variation on Reweighted Range Voting, with a runoff in each round.

As with Reweighted Range Voting, if you gave a score to a candidate who wins a seat, your voting power for subsequent rounds is reduced—the higher your score, the bigger the reduction in your subsequent voting power. In each round, the two candidates with the highest total scores enter a runoff, and your reweighted vote goes to whichever of the two candidates, if any, you scored higher. Rounds and instant runoffs continue until all seats are filled.

As in Reweighted Range Voting, voters are incentivized to give high scores to all candidates they align well with and minimum or no scores to all others. Giving middling scores to candidates they are partially aligned with could cause their more-preferred candidates to lose. However, as in the single-winner form of Score Runoff Voting, the runoff encourages voters to take the risk of losing a seat for one of their aligned candidates by asserting their ability to differentiate between their preferred candidates if they run off against each other.

As with the single-winner form, voters will have to weigh the risk of causing their favorite candidate to lose against the risk of not having a vote in the runoff.

Most proportional methods only allow voters to vote for a candidate or party, so voters in the majority are not able to exclude candidates representing a minority view from winning a fair number of seats. For example, if a majority of voters in a proportional election wanted to strengthen anti-immigration laws, they could elect a majority of the legislature that shared that view, but they could not prevent a minority of pro-immigration voters from winning a minority of seats. With Score Runoff Voting, voters might be able to block the minority from winning seats. Supporters explain that the runoff “helps eliminate small but passionate minorities.” (Note that this link repeats the myth that proportional representation helped the Nazis rise to power in 1930s Germany. Amidst the economic devastation (33 percent unemployment) and social turmoil (many Germans disdained the post-war government created when they lost WWI) of the post-war era, Nazis gained power quickly, becoming the most popular party and winning 37 percent of the vote in 1932. In a majoritarian system, they would have won a majority of the seats and taken control of the government. Though the Weimar system was flawed in other ways, it did constrain the Nazis to their proportional share of seats in the government, blocking Hitler from taking control. Instead, he was forced to declare a state of emergency and seize power through non-democratic means.)

With Multi-winner Score Runoff Voting, voters could eliminate the minority from the legislature by giving no score to any of the pro-immigration candidates and giving a low score (for example, a one) to all other candidates, so their reweighted votes would retain as much power as possible, and they would be able to vote against the pro-immigration candidates in every runoff.

Advantages

- Multi-Winner Score Runoff Voting could be used in nonpartisan races.

- It might achieve more proportional representation than majoritarian methods.

- SRV-PR encourages voters to give different scores to candidates to ensure they have a vote in each runoff.

Disadvantages

- The ballot and counting are complicated for SRV-PR.

- It has never been used in a governmental election.

- Voters must be organized and well informed to achieve fair representation. If voters differentiate their scores, their favorite might not win a seat. Then again, if they express no support, they might forego having a vote in one of the automatic runoffs.

- The majority of voters can potentially block voters with minority views from winning seats in the legislature, possibly leading to more majoritarian, not proportional, results.

Comments are closed.