In our last article on Chlorpyrifos, we asked, “Will the Trump Administration Cancel An Old, Dangerous Pesticide?” Well, it did not.

It’s only the latest sad turn of events in the history of Chlorpyrifos. It is no violation of Godwin’s law to note that the Nazis first developed organophosphate chemicals as nerve gas agents during World War II. After the war, chemical companies transitioned to using organophosphates as pesticides against insects and other target organisms, such as fungi. In 1965, Chlorpyrifos, a member of the organophosphate chemical class, was first registered in the US for uses in agriculture and in residences.

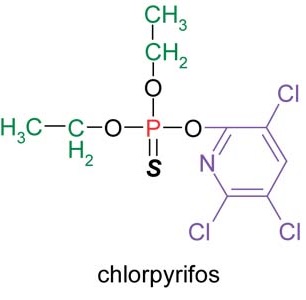

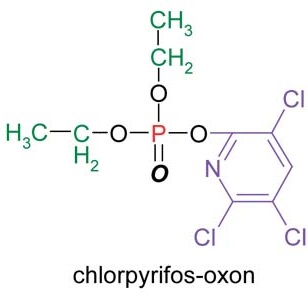

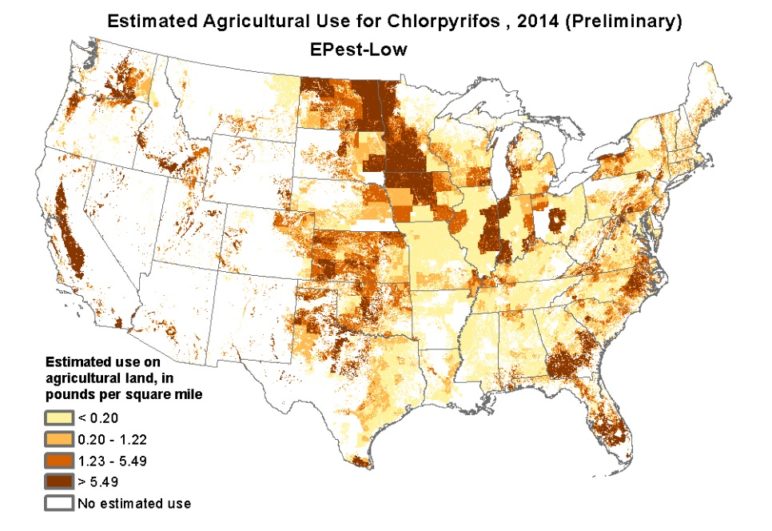

Research since then shows that Chlorpyrifos was probably a terrible idea from the get-go. EPA scientists now consider it unacceptable for children or adults to eat Chlorpyrifos-sprayed foods, including Northwest staples such as apples, pears, cherries, other tree fruits, sugar beets, lentils, and wheat. Other scientifically unacceptable exposures include those to farmworker families and their neighbors from pesticide spray drift; to workers performing agricultural tasks; and to adults and children, on or off farms, from their drinking water. Alarmingly, EPA has found that treating water for drinking via chlorination can actually convert Chlorpyrifos into its even more acutely toxic form, the oxon metabolite.

More than two decades after it was first registered, Congress amended federal pesticide laws to tighten regulatory protections, requiring EPA to “Reregister” all older pesticides first used in the US before November 1984, to bring those chemicals to current scientific and regulatory standards. This process covered over 600 chemical “cases,” individual pesticides, or groups of related chemicals. The amendments also set fees from those companies seeking reregistration to provide dedicated funds for EPA staff to review the required data. Over a third of the old pesticides were canceled, either because the data provided were insufficient or because the manufacturers made an economic decision that future sales were not likely to justify the costs of reregistration.

As scientific understanding developed, so did regulatory restrictions. Congressional amendments in 1996 required reevaluating all pesticide uses on food; established new, stricter safety standards, with special protections for children; and directed EPA to reevaluate the pesticides posing the greatest risks first. The agency was required to consider “aggregate” pesticide exposure to consumers, including from food and drinking water, and “cumulative” risks from groups of pesticides that have a “common mode of toxicity.” This included the organophosphates, of which Chlorpyrifos, still registered, is just one member.

In 2000, EPA negotiated a voluntary agreement with manufacturers to end Chlorpyrifos uses in homes, schools, and day care centers—all locations where children could be exposed. Then in 2007, the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) and Pesticide Action Network North America (PANNA), frustrated by federal foot-dragging on further protections, petitioned EPA to cancel all uses of Chlorpyrifos. The groups claimed that EPA failed to consider some pathways of pesticide exposure, such as “spray drift,” from fields to farm families and their neighbors.

In 2014, EPA published a revised human health risk assessment. In it, the agency acknowledged an extensive body of science finding correlations between Chlorpyrifos exposure and brain damage to children. Further, that brain damage occurs at exposures far lower than EPA’s regulatory target designed to prevent acute pesticide poisoning.

Eventually the courts stepped in. In August 2015, declaring it “necessary to end the EPA’s cycle of incomplete responses, missed deadlines, and unreasonable delay,” the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals ordered EPA to act on the 2007 NRDC/PANNA petition to ban Chlorpyrifos, with an October deadline. When the agency met the court’s deadline it proposed to revoke all uses on food, based on known human exposures to Chlorpyrifos from food applications and in drinking water.

The proposal might have set an extraordinary precedent. EPA advised that “the agency is unable to conclude that the risk from aggregate exposure from the use of Chlorpyrifos meets the safety standard” required by federal pesticide laws. The implication: if the Agency cannot make a formal safety finding for a particular pesticide after so many years of evaluation, then it would be obligated to cancel at least enough uses to bring the risks down to acceptable levels. Moreover, if EPA were to apply the same approach it used for Chlorpyrifos to chemical cousins that demonstrate similar effects on neurological development, then the cumulative risk assessment for other organophosphates would have to be updated accordingly. In the process, additional restrictions likely would be necessary to protect children and adults for the whole batch of neuro-damaging organophosphates.

But events took the final decision away from the Obama administration. In November 2016, after the US Presidential election put Trump in the White House, EPA released a revised human health risk assessment for Chlorpyrifos that accounted for neurodevelopmental impacts. Among other conclusions, the new risk assessment found unacceptable levels of risk for children and adults; specifically, that food exposures to all age groups exceeded safe levels, and the most sensitive group, children 1 to 2 years old, are exposed to 140 times the “safe” levels. It was a shocking finding that should have led to a complete ban of the use of Chlorpyrifos on food crops.

But the Trump administration was unmoved. On March 29, 2017, just two days before a court-ordered deadline for a decision, Scott Pruitt refused to ban Chlorpyrifos. In doing so, he limited his actions to complying with the letter of the court order, which was to make a final decision on the NRDC/PANNA petition, and denied the ban request.

Pruitt knew what he was doing. By limiting his decision to a Yes/No on the petition, he avoided setting precedents that might be applied to other pesticides. He also ignored EPA’s statutory duties to protect the environment and human health, including those most at risk—children in farmworker communities, many of whom are Latino.

So, what happens next? On behalf of NRDC and PANNA, Earthjustice promptly filed a new appeal directly to the same federal court that earlier ordered EPA to make a decision. Readers can support their action—and a ban on Chlorpyrifos—on Earthjustice’s website.

John Abbotts is a former Sightline research consultant who occasionally submits material that Sightline staff members turn into articles.

Comments are closed.