The Northwest public recently saw the second publication of quarterly oil train data for Washington. Although much about the industry is still not widely known, the Department of Ecology reports add considerably to our understanding of oil-by-rail in the region. By piecing together the figures in the new report with what we already know about the industry, we can develop a clearer understanding of how oil trains move throughout the state.

- Quantity: Oil trains delivered more than 13 million barrels of crude oil to 5 refineries and one port terminal in Washington. Overall, these facilities supplied themselves with an average of 143,721 barrels of oil per day by rail delivery, a 7 percent decrease from the last quarter of 2016.

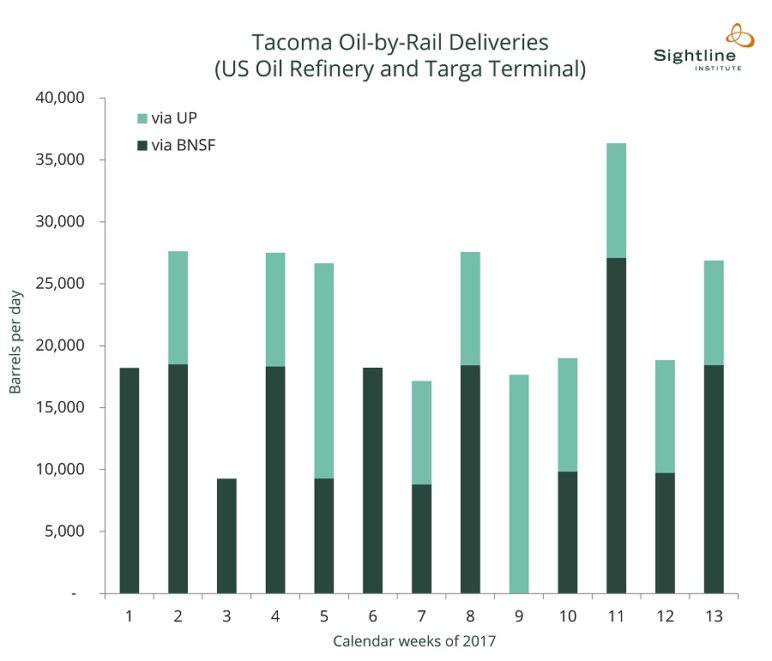

- Rail Corporations: It appears that BNSF Railway once again dominated oil train movements in Washington, handling more than 94 percent of the cargo. Union Pacific (UP) contributed less than 6 percent and delivered that oil solely to Tacoma.

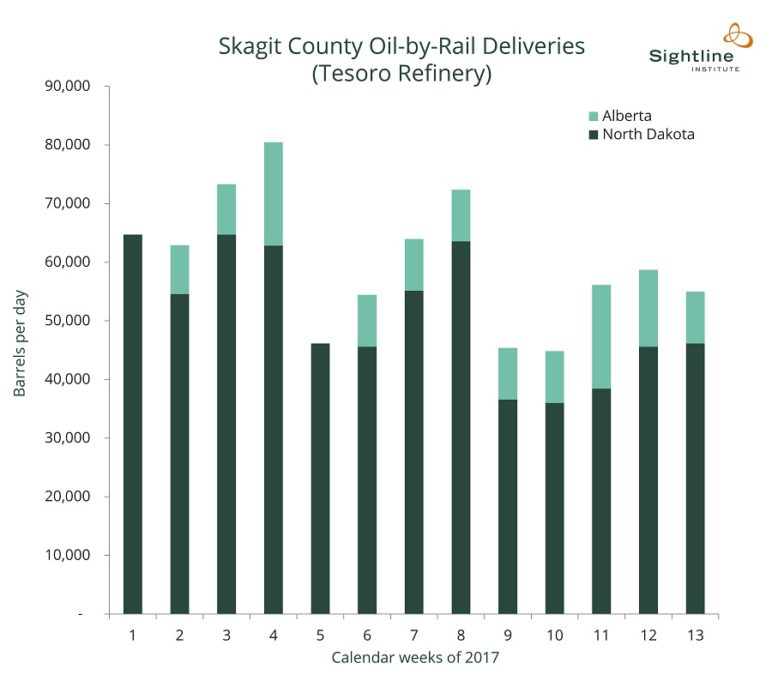

- Origins and Destinations: No loaded oil trains transited the Cascade Mountain passes. Nearly all the oil, about 94 percent, originated in North Dakota. But for one curious shipment to Anacortes, all of the North Dakota oil trains passed through Spokane, ran along the Columbia River Gorge, and then turned north to destinations on Puget Sound. A minor fraction, 6 percent, came from Alberta and entered Washington by way of Whatcom County before traveling south along the Sound to the Tesoro Refinery at Anacortes.

All oil trains in Washington are destined for one of three places on the shores of Puget Sound: Tacoma, Anacortes, or Ferndale. In Tacoma, oil trains may be unloaded at the US Oil refinery—the smallest refinery in Washington, with a rated capacity of 42,000 barrels—or at Targa Sound Terminals. In the first quarter of 2017, these two facilities accepted an average of 22,381 barrels per day, down slightly from the last quarter of 2016.

Tacoma remains the only site to receive oil trains moved by Union Pacific railroad, which was responsible for the summer 2016 catastrophic explosion in Mosier, Oregon—a train that was bound for Tacoma.

Most oil trains passed through Tacoma, Seattle, and many of Washington’s other big population centers en route to refineries on the north Sound. The Tesoro Refinery at Anacortes— the intended destination for the oil train that derailed under Seattle’s Magnolia Bridge— accepted more than 5.4 million barrels of crude oil by rail, or nearly 60,000 barrels per day on average, a decline of about 4,000 barrels per day from the final quarter of 2016.

As in the prior quarterly report from Ecology, the Tesoro Refinery was the only facility to receive oil trains from Alberta and therefore the only site to accept rail deliveries of medium and heavy crude oil. (All of the oil that Washington received from North Dakota was classified as light crude.) Based on the reported gravities of the oil, it appears that over the three-month period of January through March, Tesoro accepted by rail at most about 60,000 barrels of tar sands oil, a very dense (and very polluting) oil extracted in Alberta.

Tesoro may be transferring a portion of its oil-by-rail deliveries to the neighboring Shell Refinery, which does not have large-scale rail unloading capabilities. The future of oil train deliveries to Tesoro remains uncertain, as the Swinomish tribe is suing BNSF in federal court for breaching the terms of an easement that the railroad obtained across tribal land. In January 2017, a judge allowed the suit to proceed, ruling that BNSF had breached its contract.

Other oil trains continued north to the BP and Phillips 66 Refineries in Whatcom County. Together these refineries accepted almost 5.6 million barrels of crude oil, an average of 61,473 barrels per day. All of it was light oil from North Dakota that moved along BNSF’s rail lines in Washington.

Notoriously hazardous—prone to derailments, spills, and occasional explosions—the Northwest oil-by-rail industry is scarcely more than four years old. Only now with the publication of Washington Department of Ecology’s first two quarterly reports does the public have a reasonably accurate sense of just how much oil is moving by rail, and where.

The report also reveals that in the last half of 2016, Washington shipped out more than 1.2 million barrels of crude from refinery or port docks—whether for international export or to other domestic locations, we don’t know—roughly the amount that would be carried by eight standard tank barges or three tanker vessels. Yet the state received far more oil by ship: 22.6 million barrels, which is equivalent to perhaps 56 tankers during the same period. It works out to roughly 246,000 barrels per day brought in on tankers and barges. The second biggest delivery mechanism for oil is pipelines. And nearly all of that oil arrives by way of the Puget Sound Pipeline, which extends south from the Trans Mountain Pipeline in Canada to serve the four refineries at Anacortes and Cherry Point. During the last six months of 2016, pipelines delivered 33.2 million barrels, an average of about 182,000 barrels per day.

Among other things, the data make clear the scale of the oil industry’s ambitions in Washington. Beginning in 2012, the state faced a flurry of oil train development proposals that, in aggregate, could have moved as much as a million barrels a day by rail, a simply staggering figure. Although most of these projects have since failed, one gargantuan scheme remains: on the banks of the Columbia River in Vancouver, Tesoro aims to build a rail delivery facility capable of handling a whopping 360,000 barrels per day—two-and-a-half times as much as currently moves on the rail to every other destination in the state combined.

Notes and methods: Sightline’s analysis counts data from the 13 complete weeks that comprise the first quarter of 2017, as reported by the Department of Ecology. We converted Ecology’s weekly figures into barrels per day, consistent with industry standards. More of Sightline’s leading analysis of Northwest oil-by-rail can be found in our research series and in our July 2015 report on the industry’s plans. Our analysis of the prior quarterly report is here.

Comments are closed.